A glittering lump of fool’s gold warns that all is not as it seems in Maud Sulter’s series of photographic portraits, currently on display in the New Hall Art Collection’s exhibition space. Featuring an amalgamation of figures from the acclaimed writer Alice Walker to personal partners and companions, Sulter’s works speak to lives untold and histories forgotten. Each portrait has a sense of individuality, yet at the same time, unrivalled sisterhood. Viewing these striking portraits in-person, it is difficult to reconcile their artistry with a culture that persistently devalued the contributions of Black photographers in favour of works from elite perspectives. Whether bedecked in jewellery or adorned in theatrical period costumes, the sitters lock the viewer in confrontation with the artistic and literary representation of Black women throughout history — or lack thereof.

Maud Sulter: The Centre of the Frame features photographs by the greatly overlooked Scottish-Ghanaian artist, poet, and curator Maud Sulter (1960-2008). The series’ title, Zabat (1989), connotes a sacred dance performed on occasions of power. Made in response to the 150th anniversary of the invention of photography, Sulter’s series relocates Black women at the centre of the history of the medium. Each work takes its title from an Ancient Greek muse, and is accompanied by a poem written by Sulter herself, in which she expresses her views and thoughts on identity and representation of the muses and sitters through a spoken-word, creative style. Her work addresses the fact that Black women have often been relegated to the periphery, or more commonly are not present at all in art historical and literary canons. With this series, Sulter initiates discussions about the lack of visual and institutional representation for Black women in the art world.

“It’s important for me [..] to put Black women back in the centre of the frame — both literally within the photographic image, but also within the cultural institutions where our work operates”

In Calliope, Sulter takes the matter into her own hands. She herself is the model for this work: no longer speaking from the margins, she centres herself as both muse and artist in this portrait. Sulter casts herself not only as a Greek muse, but also as Jeanne Duval, a Haitian dancer of the early 19th century often remembered only for her relationship with French poet Charles Baudelaire — despite her own prolific career. Configuring herself as Duval, Sulter reclaims both Duval’s and her own place as the subject of the image. Calliope frames her no longer as the muse of a white, European poet, but rather now the muse of epic poetry, one which Ovid described as the “Chief of all Muses”. Channeling Duval’s voice in the accompanying poetry, Sulter suggests that in this portrait, all she wants is “my name back on my poetry and out of the adolescent scribblings whose influence is supposed to be me” —in other words: complete, artistic reclamation.

Such reinterpretations and reorganisations are characteristic of Sulter’s work. She finds new angles and vantage points with which to examine the so-called canon, revealing hidden links between European and African cultures. In Phalia (Portrait of Alice Walker), one of the first works to enter the New Hall Art Collection upon its establishment in the early 90s, Sulter enters into dialogue with Édouard Manet’s Olympia (1863). Manet’s portrayal of Olympia, a prostitute, shook the art world in its stark and innovative depiction of the female nude, a legacy still felt today in discourse surrounding representations of the female body. In contrast, far less attention has been paid to the Black maid, who stands at the foot of the bed.

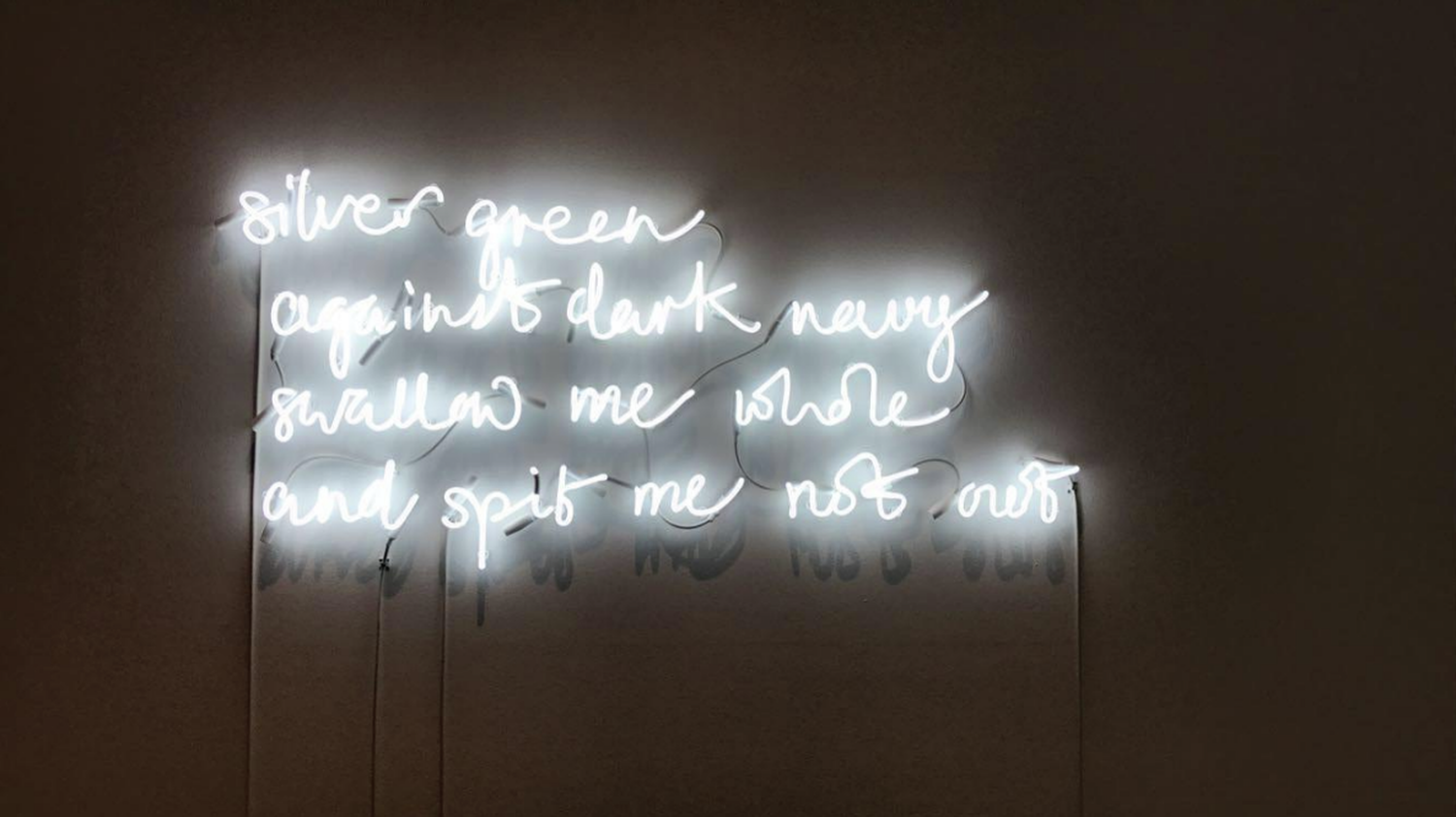

“Za’bat n.1. Sacred dance performed by groups of thirteen. 2. ‘An occasion of power’ -- possible orig. Of witches sabbat. 3. Blackwomens rite of passage [f.Egy.18th dyn.]”

Though some contemporary art historians have begun to acknowledge the racially charged aspects of this work, created a mere 15 years after slavery was abolished in France, dramatic gaps in the scholarship remain. While much is known about Victorine Meurent, who modelled for the figure of Olympia and was an artist in her own right, the life of the model who posed for the maid, Laure, remains shrouded in mystery. In Olympia, Laure holds a bouquet out to the painting’s eponymous subject. In Phalia, Walker’s own bouquet, whose flowers bear the vibrant colours of the Ghanaian flag, alludes to this pose. Just as in the case of Duval, Sulter recalibrates Manet’s work, placing Laure, and Sulter’s own national identity, at the centre.

Part of the gravity which Maud Sulter: The Centre of the Frame holds can be found in its curation. Speaking to the collection’s assistant curator, Naomi Polonksy, it became clear that locating all nine muses was completely impossible, partially due to the private collection of these pieces, and partially due to Sulter’s lack of recognition in the mainstream. However, where absence was felt in the quantity of pieces reunited, there was a stunning sense of uniformity in the curation of the pieces that were there. Polonsky detailed how Sulter laid out specific visual and practical instructions for how this series should be presented, from preserving the original framework, to ensuring the font of her poetry, displayed beside each print, was the same, and how she liked it — amusingly Sulter even requested a specific font, apple chancery, as the typeface for the titles, which has been honoured in this exhibition. Though Sulter never received the recognition she deserved in her lifetime, her power can be seen in the strength of her curatorial vision when presenting her own work to the public.

This iconic series celebrates the medium of photography on its 150th anniversary. Created through the process of dye destruction, now a medium almost obsolete in the age of digital photography, Sulter’s works are rendered even more exceptional. In Calliope, Sulter poses alongside a daguerreotype, a nod to the earliest forms of photographic representation. Yet here, the image is concealed in shadow — perhaps a reminder of the absence of Black women, both behind and in front of the camera, in histories of the medium.

“Black women have been using cameras since they were invented. Part of the difficulty for those of us engaged in the reconstruction of that participation, our herstory, is the lack of documentation and the difficulties inherent in trying to reclaim it.”

Sulter herself has largely been excluded from mainstream narratives. Very few archives remain of her life and work, and what little does exist is often rare and inaccessible to the public. With this exhibition, the New Hall Art Collection amplifies Sulter’s voice, which for so long remained stifled. The show has sentimental significance for the New Hall Art Gallery, not only as Phalia was one of the first works to enter the collection, but also for Sulter’s relationships with other artists in the collection, such as her partner, Lubaina Himid.

Showing Maud Sulter in Cambridge University, the epitome of one of the ‘cultural institutions’ Sulter critiqued for its lack of diversity, has further and deeper significance. Remembering that curation and display were key elements of Sulter’s practice, the donation of Phalia to a Cambridge college must therefore be seen as a deliberate and intentional act to bring these discussions to such institutions, as part of a larger programme of decolonisation.

Zabat was created in 1989, a response to Sulter’s frustrations with prejudices in the art world. Yet in 2021, when racial violence and the underrepresentation of Black voices remains widespread, the series remains pertinent. Sulter’s series shouldn’t be unique in its portrayal of Black women as protagonists, and yet in the mainstream, it still is — a testament to the continued importance of Sulter’s work today. When it comes to acknowledging Sulter’s contribution not only to exposing the injustices of the art world, but the medium of photography itself, we can only hope that this exhibition is just the beginning.

Maud Sulter: The Centre of the Frame spotlights the work of Scottish-Ghanaian artist Maud Sulter (1960–2008); drawn from public and private loans from across the UK. Maud Sulter (1960–2008) was a Scottish Ghanaian artist, poet and curator. Sulter grew up in Glasgow and moved to London at the age of 17 to study at the London College of Fashion. She later earned a Master’s degree in Photographic Studies from the Derby School of Art.

The New Hall Art Collection is a collection of modern and contemporary art by women at Murray Edwards College. The largest of its kind in Europe, the Collection is on display across the iconic Brutalist building, designed by Chamberlin, Powell and Bon as a manifesto for the education of women. You can find out more about the exhibition and the New Hall Art Collection here: https://art.newhall.cam.ac.uk/event/maud-sulter-centre-frame/

Varsity were kindly invited by the exhibition’s curator to tour the exhibition for a review.