Content note: this article includes detailed discussion of eating disorders

I lay in bed writhing in physical pain. Sheets twisting into tourniquets which snaked their grip around each limb, slithering up to my throat and constricting me so tightly that I had to fight for each shaking, sob-choked, breath. Guts which threshed and threw themselves over one another, lassoing each organ and dragging them down to lie at the pit of my stomach. A heart which had sunk to lie tilted in my lower abdomen, beating feverishly as it attempted, with each weak and irregular pulse, to bring itself home. “Home” was the word I was whispering to myself. I wanted to go home. I was lying in my bed, but I didn’t feel at home. Never had I felt so distinctly out of my own body, and yet, paradoxically, excruciatingly aware of its every crease and fold against the duvet’s own. Aware of each touch of my inner thighs against each other when I turned on my side. Aware of the smooth mound of my stomach as it reddened with each pound my fists made against it, mirroring the pillow’s own pummelled, similarly once-white dune. My body felt at once mine: inescapable, infuriatingly human in each perceived flaw, and entirely foreign — burdensome, a problem to solve, cold, unfeeling, clay to mould.

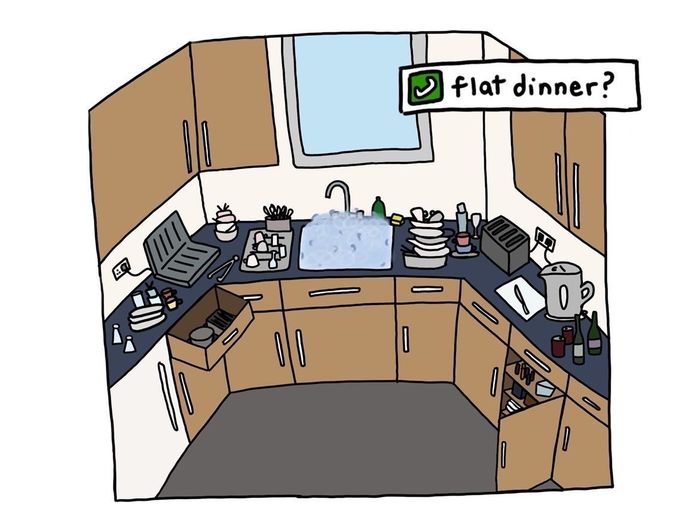

This was on 23rd December 2019 and was provoked by a Christmas dinner with friends. I had been preparing a chicken for hours, alongside three Linda McCartney sausages for Eva (the remaining ones in the pack would sit unattended in my carnivorous family’s freezer until the following year). Each time I opened the oven to poke the flesh with a blunt knife, the drinking glasses would steam up and so would my glasses, and smoke I could not see would fill the room with a heavy heat. Zoe brought potatoes which she insisted were her own, but we all knew were her dad’s work, and Talia had contributed… Christmas crackers? She couldn’t cook. The contents of our dinner were not just what spilled out of my oven and onto every available surface, but also thoughtful Secret Santa presents gifted by girls who clearly understood a £10 limit as an unwelcome advisory, ripped open in the dim light of attempted ambience (two candles from the back of my cupboard) and frantic, clamorous joy. Joy of a childhood tenderly evoked, then raucously celebrated with unending love, “ho ho ho” wrapping paper, and time which stretched out untethered to reality. My father’s anxious trips to the kettle to not-so-subtly remark at the flickering time on the oven, still set to Daylight Savings, and winking at us with its welcoming glow, did not manage to tether it back. We danced and drank until we collapsed onto my old green sofa, us worn with alcohol and it worn with age.

“Colours, tastes, Christmas cracker jokes which sprinkled my kitchen like confetti, were now numbers which swirled kaleidoscopically around my bedroom”

Yet the elements of the evening which comprised the former list, having spilled out of an oven and onto tables, were the only contents which could be later tracked, punched into my phone at 2am. Its neon blue light shone caustic on my eyes as they winced, wet with tears and dry with exhaustion. My fingers were fast with anxiety and slow with apprehension, and where once I had felt a glee which bubbled up and over like the Prosecco whose cork I poorly popped and whose cheap, apricot taste had washed down each course, I now experienced a deep, cutting pain. Each spoonful and sip was hastily recalled, converted from an extra forkful of stuffing to a “why the fuck would you have eaten that?”, from a toffee penny whose wrapper had then adorned my reindeer hat’s antlers to a “you greedy bitch”. Colours, tastes, Christmas cracker jokes which sprinkled my kitchen like confetti, were now numbers which swirled kaleidoscopically around my bedroom, filling it like our laughs had taken up the kitchen downstairs, bouncing off the walls like I had done after too many chugs of sweet white wine. Having gone down like ambrosia it now sat in my stomach like tar, sticky with guilt, regret and however many calories per bottle it had — a number I have tried to wash away with formals and pres and dinner dates and whose taste, acerbic and shameful, I have never quite been able to forget.

The government’s requirement that every restaurant with over 250 members of staff provide calorie information on its labels came into force on 6th April this year. The act of deleting my tracking apps, at once liberating and terrifying, will no longer be the same act of rebellion for any brave souls who find themselves in the same position as I was, less than three years ago. They will now find an autocratic reign of numbers to be inescapable. For those who suffer from eating disorders (1.25 million in the UK, as estimated by Beat) this legislation will be crippling, the implicit nudge to choose the lower-calorie option an ever-present ratification of the “eating disorder voice”. Even when other menus are available, such actions spark unproductive and harmful conversions over the table — a weight-watchers aunt’s, health-conscious mother’s, or even bulking brother’s assessments and calculations, potentially playful in intention, can and will be warped by such a voice into value judgements. It was value judgments such as these which caused me to label myself “greedy”, “disgusting”, “unworthy”, and far worse, as I lay in bed that evening.

“Since I chose recovery, my body has slowly become my home again”

These measures are not only damaging, but do little to fulfil their purported aims of creating a healthier population. Suffice it to say that issues with the health of the British public will not be solved by calorie counting, but instead must be tackled at a systemic level by combating poverty, increasing the availability of, and lowering the price of, nutritious food, and sponsoring education. None of which this Conservative government is willing to do. Conservative candidate Darren Henry told voters at hustings that people relying on food banks should focus on “maybe being able to manage their budget”. In fact, food banks, as the alleged manifestation of non-governmental strategies to overcome poverty, are lauded. In 2017, Jacob Rees-Mogg called them ”uplifting”, given that “the state can’t do everything”. The state can be expected to work towards increasing the health of the nation, but instead, this government’s rhetoric of personal responsibility bleeds now into health, and with it comes the inevitable blame they can now place on the population for our strain on the NHS that they have underfunded. And at the altar of this laissez-faire mythology are sacrificed all those for whom numbers mar, and control, their lives.

Since I chose recovery, my body has slowly become my home again. It and I have moved together, tectonically shifting, and in doing so patching over the raw, bubbling, and fiery painful magma scars left where I had torn myself to shreds in my counting and assessing. Each tear I may cry now, rarer each passing month, at least falls onto cheeks which feel my own, etching rivulets, not wounds. I can hold myself in the dead of night, wrapped in arms which no longer serve as sites of fury and frustration, never shrinking quite small enough, but instead are simply the appendages which start at my shoulder and end at the hands which can wipe the tears off my face, pick up my computer, and pen this article. Christmas (or Bridgemas) is now a cause for celebration, not torment, and I can taste cheap wine and lukewarm pizza on my tongue, not its acidic numerical equivalency. I can be comforted by thoughts that, even if formed of words which tumble over one another in their race to the forefront of my consciousness, rushed and confused, excited, or perhaps unkind, have at least left the numbers which once accompanied them to gather dust and cobwebs in the almost unreachable lacunae of the back of my mind. Let’s condemn each menu printed with such unfeeling and joyless calculations to wherever the appropriate non-metaphorical iteration of such a place may be.