A black square in a red revolution

On the centenary of the October Revolution, Alex Reeds takes a moment to explore the transgressive and revolutionary qualities of Russian painter Kazimir Malevich’s work

History has a habit of overlooking art in favour of politics in the context of revolutions. The rising up of the masses, the overthrowing of a tyrannical system, the dawning of a new age: these are the phenomena that most commonly characterise revolution.

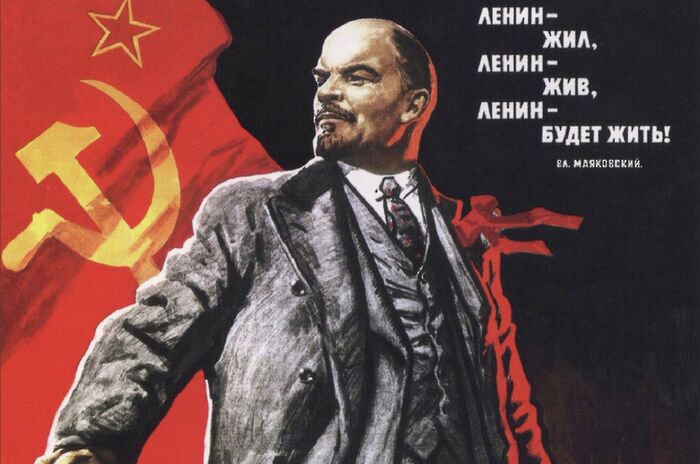

This is certainly the case with regards to the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution, which last week marked its 100th-year anniversary. Images of Lenin’s ruthlessness, Trotsky’s idealism and the Provisional Government’s incompetence dominate our perception of the events of 1917. However, it was the Russian painters, poets and writers who had been addressing many of the revolutionary ideals, embodied by the October Revolution, long before 1917. The ambition of the Russian avant-garde’s desire to launch a revolutionary struggle against artistic modes of perception was unparalleled and arguably foreshadowed the famous political upheavals of 1917, which we most notably associate with the theme of revolution in Russia.

Kazimir Malevich (1878-1935) was one of these revolutionary figures in the Russian avant-garde. Having experimented in the early stages of his artistic career with different styles ranging from Primitivism to Cubo-Futurism, it was the exhibition of his work Black Square in 1915 that cemented his place among the pioneers of abstract art. The very name of the painting, Black Square, is a deliberate misnomer: despite its appearance, the work is neither a square, nor is it black. None of its sides are parallel to the frame and it is painted from a mix of colours, none of which is black. How could a painting so simple be so radical? Therein lies the beauty of Malevich’s magnum opus. Behind the surface of this perfectly symmetrical shape exists a revolutionary system, which Malevich named ‘Suprematism’.

“Malevich considered his square to be ‘alive’”

Malevich believed that the problem with the naturalist art of his predecessors was the desire to simply depict reality at the expense of creating new forms. He dreamed of a new art form that would have no subject and be made up solely from shapes and colours: the pure aesthetic would reign ‘supreme’ over the image or content. Suprematism signalled this rejection of representational art and liberation from pictorial conventions.

It is in this context that Black Square becomes such a revolutionary work of art. Its importance as the first Suprematist painting is undeniable. It embodies the supremacy of colour and form in its simplicity and the principle of revolution in its challenge to established modes of perception. Malevich considered his square to be ‘alive’, and concurrently addressed the question of how it could activate the body of the spectator. Thus, the idea of ‘feeling’ art was critical for Malevich. Indeed the contemporary viewer most commonly ‘feels’ a sense of anger and disappointment upon seeing Black Square. Comments such as ‘Is that it?’ and ‘Even I could draw a black square on a canvas’ rank among the most popular of those who visit Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery to see the iconic painting. This is one of the perennial discussions that define abstract art. However, as already noted, Black Square does not depict a black square. It was not intended to represent a real object, but rather a perfect geometrical form, liberated from the strictures of art.

The ambition of Malevich’s ideology seems almost laughable to the contemporary critic, especially having been conceived amid the chaos of the First World War. However, at a time when revolutionary sentiment was brewing in all walks of life, anything seemed possible to the most radical thinkers. Sadly, it seems that Malevich’s complex principle for artistic revolution was as misunderstood in 1915 as it remains today.

Despite its promise, and the praise garnered by the Russian intelligentsia, Malevich’s Suprematist theory did not strike the same chord with either the Bolsheviks or the illiterate masses of Russian society. Suprematism was a short-lived movement, displaced by the more pragmatic Constructivism, which proclaimed the need for artists to become active builders in society by using art to create material objects. Malevich’s focus on art for art’s sake was inherently incompatible with the Bolsheviks’ revolutionary principle, as art needed to be embraced as a means to indoctrinate the masses. Nevertheless, Black Square is rightly considered a seminal work of abstract art, representing a decisive break from past conventions. It is ironic that despite Malevich’s wish for painting to be free from political and social content, Black Square has become one of the most recognisable symbols of revolutionary Russia.

Just as Suprematism was displaced by other art forms, so too was Malevich’s black by the red of the Bolshevik revolution. However, revolution should not be defined by a single colour: the Russian Revolution was as much a political upheaval as it was social and artistic. On the centenary we should remember this. Although there would likely have been no revolution without Lenin, Malevich and his artistic associates also played their part

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025