Balthus’ masterpiece is creepy. But should it be removed by the Met?

Lucian Clinch assesses the recent controversy surrounding Balthus’ painting Thérèse Dreaming, unveiling the problems of moral censorship in art

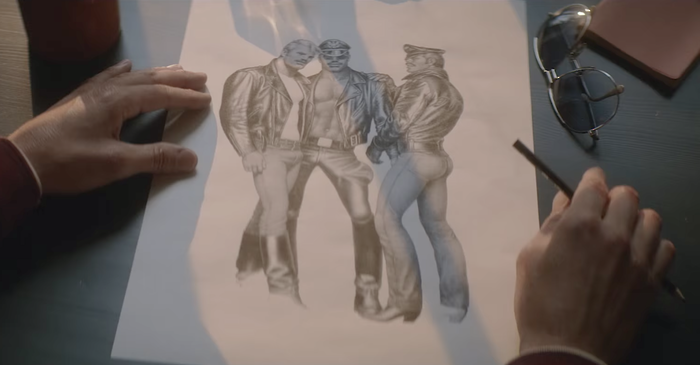

The quest to properly define any discipline is a notoriously difficult task, and perhaps no subject is harder than art. Art remains diffuse in its media, broad in its subject matter. But across the startlingly diverse creations that we term ‘art’, several factors are constant. It challenges what we regard as political consensuses, societal norms, and the status quo: it challenges our own emotions. Art has provided a tool for important transgressions, as shown in the recent Tate exhibition, Queer British Art. Another exhibition too, Basquiat at the Barbican, shows an art which defended and supported a burgeoning urban subculture in 1980s New York.

“Whatever one may think of its content, Thérèse Dreaming is as legitimate for a gallery as the Mona Lisa”

It is in New York that the latest battle for freedom of expression is being fought. A petition started by Mia Merrill, an American HR director, has called for the Metropolitan Museum of Art to remove a particularly “suggestive” painting. Thérèse Dreaming by Balthasar Klossowski de Rola (better known as Balthus), on show in New York since 1998, is a surrealist depiction of a young woman sitting on a chair. One leg is raised to reveal her underwear, and a cat laps at a bowl of milk nearby. She sits, according to Merrill, in a sexually suggestive way, who also questions why the Met would want to support this voyeurism and obvious sexualisation of a child.

This is a slippery slope. It is undeniable that the painting is creepy, especially considering Balthus’ own predilection for underage girls. Born in Paris to Polish expatriate parents, he often painted girls in eroticised poses, yet always denied any paedophilia charges. But why should a museum have to drown its viewers in context? Museums are for the enjoyment, consideration, and discussion of art and, whatever one may think of its content, Thérèse Dreaming is as legitimate for a gallery as the Mona Lisa.

It is worth considering the current climate of heightened sensitivity to sexual crimes. With the silence breakers winning the TIME Person of the Year, and with Hollywood in revolt against its abusers, the petition of Balthus’ painting sits squarely within the same discourse. However, it fails to take into account the differences between art and real life. For all its impeccably deployed realism, Thérèse is a painting of Balthus’ neighbour, asleep and dreaming. It is voyeuristic in the sense that we are intruding on a private moment, but some of the most beautiful art preys on the intimacy of its subjects. Take Vermeer’s Girl Reading a Letter at an Open Window. It is unimpeachable in its moral compass, but here too we as the viewer are undeniably peeping, if only for an instant, on a young woman’s private moment.

One accusation that cannot be levelled at Balthus is that of pornography. The painting was not created purely for sexual gratification, and is too stylish to be so. The care given to her raised arms, the wicker of her chair, and the pillow lightly supporting her back is equal to that given to the delicate arrangement of her legs. Its ‘realistic’ qualities certainly ought not to bring the painting in for more criticism. When asked about her provocative post, Balthus merely responded “it is how they [young girls] sit”.

A petition calling for a painting to be removed from the public eye inevitably raises questions about the suitability of other artistic output. It seems a dangerous route to traverse. Should we ban Lolita, for instance? Described by Martin Amis as both “irresistible and unforgivable”, Nabokov’s novel about paedophilic fervour for a young girl is silky in its prose, yet transgressive in its subject matter. Stuffed full of intertextual references and puns made more impressive by knowing that English was Nabokov’s second language, Lolita is normally invoked today only to be praised.

A comparison between Thérèse and Lolita provokes an unsettling conclusion. Thérèse Dreaming is condemned because it contains supposedly morally dubious material and its painter had creepy tendencies. Lolita is held up as a work of great substances despite its decided moral dubiousness, and most crucially, due to the innocence of its author. For the average consumer, both are equally immoral. The difference between the two works is null and void, and reeks of a double standard.

Despite the intellectual and aesthetic pleasure that can be gained by viewing art for art’s sake, the modern public is worthy of better. We are right to be challenging, querying and questioning the art that hangs around us, and wonder at the motive of the artist to paint such an unsettling work as Thérèse Dreaming. We can wonder at its inherent morality, too, but art is inanimate. It cannot fight back and answer for itself. It deserves to be contemplated, discussed, and perhaps even rejected by its viewership, but it must not be removed

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025