Beauty yet to find

In his column this week, Joseph Krol explores the unexpected link between Rupert Brooke’s poetic vision of Grantchester and the idealism of the Rococo art movement

It is odd, visiting Grantchester in the winter. There are no punts crashing their way upriver, nor any picnickers eating strawberries and cream. The garden parties remain remote, while the spirit of summer seems but a distant dream.

It is a far cry from the pretty village we know, immortalised by Rupert Brooke in his poem The Old Vicarage, Grantchester. He is best known for his war poetry, and it is easy to imagine the work as written by a man dreaming of peace, while surrounded by carnage. In fact, it had a rather different genesis: he was living unhappily in Berlin, merely hankering for a place that was far enough to be idealised, yet close enough to be accessible.

“Brooke, like Watteau, knew the bleak answers to his questions”

What he described was Grantchester. His enthusiasm is utterly infectious: when he describes how “you may lie / day long and watch the Cambridge sky”, as he asks “Is there beauty yet to find? / And certainty? And quiet kind?”, one’s instinct is to say yes: those sunlit uplands, nestled as they are between examinations and the long vacation, seem perfectly evoked.

Most Cambridge students have visited the village in summer, if they have visited at all; in those meadows, with the sun shining and the river winding lazily by, it can almost feel that one is at any point in time. Some communion of souls past results, and as one sits laughing uproariously with friends and lovers, reality can seem quite removed.

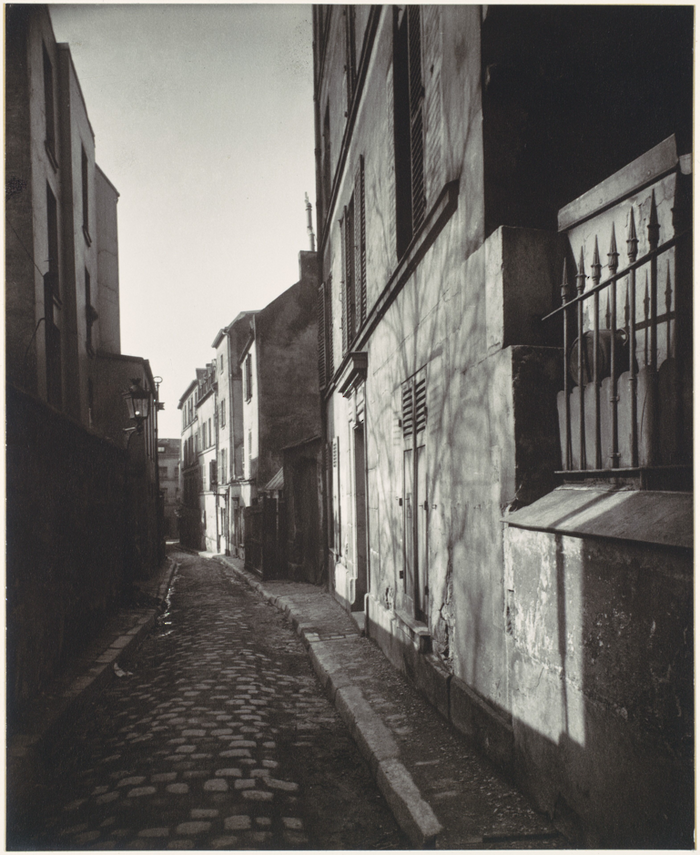

If we seek to understand the emotions wrought by these idyllic experiences, it is natural to turn the genre of Rococo. It was on its face a positive, joyful movement; inspired by a new age of French frivolity, paintings often featured elaborate depictions of carefree youths lounging on riverbanks, of sumptuous parties and the quintessential richness of life. Brooke’s Grantchester seems a more British, understated version of it.

The genre truly announced itself when artist Jean-Antoine Watteau presented the Academy with The Embarkation for Cythera. Lovers are shown lining up, ready to be taken to Cythera, the birthplace of Venus. It is sensuous, dreamlike, mercilessly idealised and yet somehow glorious. However, his fellow artists noticed something astray: if they were already partnered up, surely the painting must depict a departure from the island?

I think he knew precisely what he was doing. All it takes is a slight mental readjustment, and the meaning of the painting is almost turned about its axis. Full of the new-found fervours of youth, happy couples rush in earnest, ready to sail into a future that they are sure will be wonderful, but of which they can know nothing. Perhaps some will be right, but most will be disappointed. What, after all, can one see in those impressionistic brushstrokes? Nothing very clear…

I fear Grantchester tells a similar tale. There is no longer “quiet kind”, and certainty? I am not sure it was ever there. Brooke knew he was pining for a place his mind had invented, full of youth’s confidence. Moreover, this was a place where jaded realism could have no dominion: in Brooke’s imagined Grantchester, “When they get to feeling old / they up and shoot themselves, I’m told…”

Brooke, like Watteau, knew the bleak answers to his questions. “Deep meadows yet, for to forget / the lies, the truths, the pain”: this is what we really seek in Grantchester. We seek to cleanse ourselves of the harsh realities embodied by that city down the river… it is the closest we will get to that old dream of Cambridge’s beauty, its people, its riches, without the trials of the work and stress. It is a symbol as much as a village.

We all know the paradox of youth. It is a sense that all things must be done now, for things will only grow worse; it is that desire to revel while in one’s prime, and yet an acknowledgement that one has not the experience to make the most of it. It is a time of lassitude and liveliness, a time of self-critique and self-improvement, and of so many other perfect contradictions.

We can by all means enjoy Brooke and Watteau, and their realities that we only wish could exist. But we must share in their doubts. We can reflect on the symbol, but we cannot let it become our expectation. Some of us will matriculate and graduate without ever reaching true happiness, but we cannot lose ourselves in endless comparisons. There is a long time yet for pleasure, and a long time yet for pain. For sure, there is beauty yet to find – but we must not be so short-sighted as to believe that it must be here

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025 News / Cambridge Union to host Charlie Kirk and Katie Price28 April 2025

News / Cambridge Union to host Charlie Kirk and Katie Price28 April 2025