Poetry and the horror of time

In his latest philosophical musing, Joseph Krol contemplates his college’s clock, the Chronophage, and delves into other representations of time and mortality in poetry

In the middle of the journey of my degree, I found myself standing once again in front of the Corpus Clock. It was one of hundreds of times I had walked past it, but the first in a long time when I stopped to actually consider it as a work of art. It is so easy to ignore, suffocated as ever by tourists marvelling at the disorder in the lights, yet it tells the most harrowing story of each of our lives.

The designer, John Taylor, knew precisely the unsettling effect he set out to achieve. He described the horrendous locust perched on top, known as the Chronophage, thus: “He’ll eat up every minute of your life, and as soon as one has gone he’s salivating for the next.” Countless effects combine to give this impression: It is especially haunting to first hear the chains scraping against a coffin buried within the college, which form the chimes of the hour.

Throughout my studies here, it has been ever-present, plodding miserably along in the background. It was ticking at the second of my matriculation, and it shall continue inexorably in its task until I graduate. This existential terror – this fear of the future – is difficult to express in painting; it is complex, multilayered, and hard to express as a reflection of the instant. There are, of course, exceptions, like Poussin’s great Et in Arcadia Ego, in which we see shepherds reading that this interred corpse, too, had walked the same hills that they did. In my opinion, however, the greatest efforts are through the medium of poetry. Rhythm, metre, and some enforced direction can all combine to form a better depiction than any snapshot could wreak.

“Herrick was, in every sense, a poet of the country”

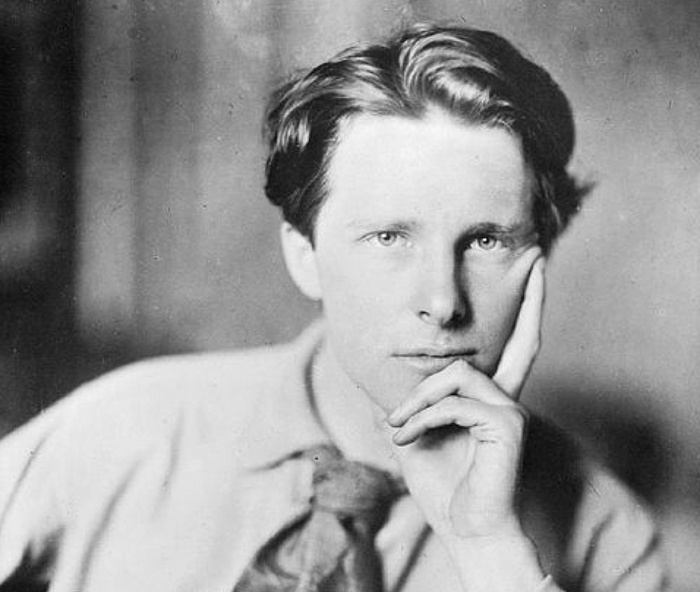

From their biographies, one might expect Robert Herrick and Gerard Manley Hopkins to be similar poets. Both were born in London; both attended Oxbridge (Herrick at St John’s, Cambridge, Hopkins at Balliol, Oxford); both went immediately into the clergy (neither marrying); both reflected on religion, nature, life and death through their poetry, albeit two centuries apart. How, in similar circumstances, did their views diverge so greatly?

Herrick was, in every sense, a poet of the country. After graduating, he became the vicar of the tiny Devon village of Dean Prior. The duties were never too exacting; he had plenty of hours to while away writing poetry, and plenty more to spend in nature, admiring both the arcadia itself and the people who lived within it. Nowhere is this more apparent than in his delightful work Corinna’s Going A-Maying, with its arresting opening couplet “Get up, get up for shame, the Blooming Morne / Upon her wings presents the god unshorne.” The poem is an exhortation to a woman to join him in pastoral pleasures. Rather than being lazy, he claims, one should make the most of the springtime of one’s life, for it is sure to end much sooner than one expects. Indeed, the poem runs with a profound awareness of death, erupting forcefully into its latter lines: “We shall grow old apace, and die / Before we know our liberty.”

Hopkins’ experience was rather different. He never progressed much within his Jesuit church, and at every point in his career – whether in London, Oxford, Manchester, Liverpool – he was overworked and depressed. Nature was never a way of life for him; rather, it provided a certain escapism. He obsessed over paragons of the natural – kestrels, poplars, kingfishers – and it is the resulting idealised sonnets which constitute his best-known poetry. When he turns to face humanity, however, his verse becomes instantly more mournful.

One of the most powerful examples is The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo. As its title would suggest, it is a poem of two halves. In the first part, the poet desperately asks if one can keep beauty from vanishing away, concluding only that “nothing can be done / To keep at bay / Age and age’s evils,” and that “wisdom is early to despair”. The second half brings a temporary hope, which soon collapses into illusion; some disembodied spirit replies to the narrator, claiming that there is some way to delay this loss of beauty. Yet, they say, it is “not within seeing of the sun”, that it lies in some vague “yonder”. It seems ever-imaginable, but one can never quite reach out to touch it.

The views contrast. Both agree that the end is approaching faster than we dare dream. However, whereas Herrick advocates making the most of it all while we’re here, Hopkins seems at once quite fretful and utterly resigned. In all of this, there is a question which we must ask ourselves: With whom do we side? Is it Herrick, with his optimistic fields of beauty and youthful joy, or Hopkins, with his more measured realism and ultimate lack of a solution?

Whatever we choose, the clock will tick down unceasingly. But we cannot let the horror overwhelm us

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025