The artistic power of the rainbow flag

As LGBT+ Pride month draws to a close, Emily Blatchford discusses the community’s most recognisable piece of art – the rainbow flag

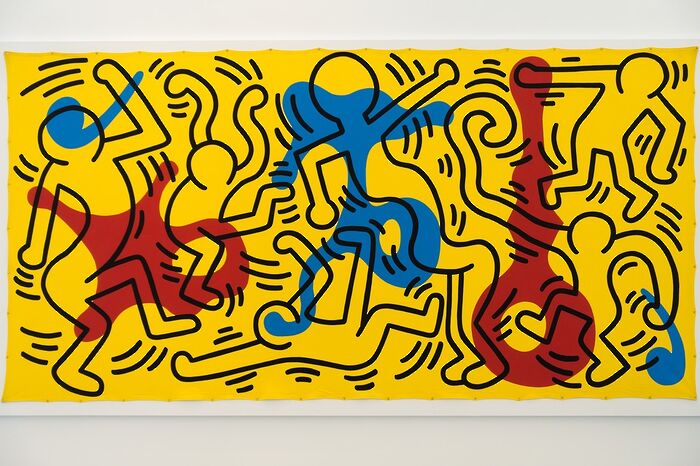

Like the protest art of the Woman’s March or the March for Our Lives, LGBT+ art is a distinctive form of self-expression. It makes public what decades of oppression have worked to keep private – battling censorship with an advancement of visibility. It revels in difference rather than assimilation and potently harnesses the ability to shock. From the witty protest signs of “If God hates gays why are we so cute” or “Bisexuals are just confused by your ignorance!”, to the artwork of Andy Warhol, David Hockney and countless others, LGBT+ art is expressive of individual identities.

In the face of dark repression, the flag is defiantly sunny – even jubilant

Yet alongside these, I have not mentioned what is perhaps the most iconic piece of art to be associated with gay rights: the rainbow flag. This is not a symbol of personality but one of community.

Gilbert Baker, a San Francisco artist born in 1951, created the original rainbow flag in 1978. In its initial incarnation, Baker’s flag consisted of eight colours – two more than the flag now uses – and each colour was assigned a symbolic meaning. The band of hot pink stood for sexuality, red for life, orange for healing, yellow for sunlight, green for nature, turquoise for art, indigo for serenity and violet for spirit, in this order. It was sewn together by a group of 30 volunteers and displayed for the first time in the United Nations Plaza in downtown San Francisco in June 1978.

The design has undergone a variety of revisions since its debut, first to remove colours and then to subsequently restore them based on fabric availability. Typically flown horizontally like a rainbow, its most common variant consists of six stripes: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, and violet. In the face of dark repression, the flag is defiantly sunny – even jubilant. It is a celebration in confronting continual oppression, an iconic sign of solidarity and a symbol of pride and hope.

Yet, while these colours are used to express a happiness, they also continue the crucial role colour has played in LGBT+ history. In Victorian England, green was associated with homosexuality (for instance, Oscar Wilde’s green carnation). The Nazis used a pink triangle to signify gay males in concentration camps – a symbol later repurposed by LGBT+ activists, such as the various Pink Panther movements beginning in the 1970s. Similarly, purple became popularised for the lesbian and gay communities with ‘Purple Power’. The reclaiming of these colours from their frequently oppressive histories demonstrates the effectiveness of art as a tool to harness and re-establish identity.

Like other flags, the rainbow flag expresses a sense of commonality and community, collective goals and shared values of equality. However, unlike other flags tied explicitly to patriotism and nationality, it also acknowledges the diversity within the community through its variety of colours. Its design has been extended and adapted for the various communities which fall under the banner of LGBT+: there is the magenta, lilac and blue flag for bisexual pride; the sky-blue, white and pink of the transgender flag; and the asexual pride flag, with its black, white and grey contrasted by a bold strip of mauve. These colour choices each represent various aspects of the communities they are used by. The monochrome colours of the asexual flag, for example, represent the varieties of the asexuality spectrum, with its bright colour stripe symbolising community.

The rainbow design, while representing LGBT+ groups as a whole, allows for these pluralities of identity to be celebrated. It highlights a natural beauty; perhaps a different comeback those wielding ‘God hates fags’ signs and centuries of backlash and supposed ‘cures’.

Though we might like to think that we live in a different, more accepting age, the rainbow flag’s continuing relevance as a piece of protest art demonstrates that there is still some distance to go. Now a symbol marked indelibly into our culture, it is arguable that it is far more effective than other protest arts.

As visual art, it is able to be both personal and educational. Anyone who is does not identify as LGBT+ can see the rainbow flag and understand it is the expression of another community, deserving of positive attention and rights.

A literal embodiment of visibility for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, the flag’s use – by institutions such as Cambridge colleges as well as individuals – stresses that those who identify as LGBT+ are diverse and wonderful people. It suggests that the issues they face are issues everyone should care about. It is a voice of a community, refusing to possess a definite viewpoint, using its very simplicity to be inclusive.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025