Emma Low and the invention of women

Helen Grant explores the work of Leeds-based potter Emma Low, whose body-positive and intersectional works reset the terms for how women’s bodies should be presented

‘Do women have to be naked to get into the Met. Museum?’ Feminist activist artists 'The Guerilla Girls' have been keeping tabs on this question since 1989, when they first paid for an advertising campaign that would see it put on display on the side of New York buses. In that year, less than 5% of the artists in the Modern Art sections were women, while 85% of the nudes were female. In 2005 the figures on the posters were updated to show the new figures of 3% and 83%; in 2012 these saw negligible improvement in 4% and 76%. Every so often, the question is re-released, or sometimes adapted: ‘Do women have to be naked to get into Boston Museums?’ ‘Do women have to be naked to get into U.S. museums?’ And, in Paris, ‘Est-ce que les femmes doivent être nues pour entrer au Metropolitan Museum?’

A ceramicist whose work focuses entirely on nudity should not, at least on paper, offer much of a solution to an over-proliferation of naked women in art. Yet Emma Low, also recognisable under the handle ‘Pot Yer Tits Away’, has managed to do just that. The culprit, after all, was never the female body itself. Low makes naked pots. Most of her work focuses on breasts – ‘tit pots’– although she also makes penises and bellies. Her work is notable for its intersectionality, and also for its realism. She takes commissions, and makes her pots directly from photographs, or sometimes from sitting models. Before sending them back to the subjects, she posts pictures on Instagram, for which she has gained an impressive 63.3k followers. Somehow, in spite of a business model based on making women into objects, she manages to embody modern feminism. How?

The consensus view of breasts in our society is one of contempt. Breasts are public. They don’t make someone a woman, but we equate them with women, and thus subject them to the same vitriol suffered by women as a group. We give them responsibilities: feeding (not in public), arousing (slut). We remember them when they are adjectives to accompany ‘implant’ and ‘cancer’. When we think about adjectives to describe breasts, we base them on whether or not they merit our lechery: ‘perky’ (optimum), ‘saggy’ (what a shame).

We don’t know what breasts look like. Their social image, which is round and high up and white, is a total distortion of their actual appearance, which is often only some or none of these things. We use tape and bras to make them look like how they don’t look. Lately, with body positivity, we’ve given them permission to be a bit smaller; now we can applaud them for being neat and petite, attached, perhaps, to a Victoria’s Secret model in a pretty bralette. And then maybe they can foster other people’s weird orgasms, like in Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag: “They’re so fucking tiny! They’re hardly even there! Where the fuck even are they?”

‘Pot Yer Tits Away Luv’ depicts breasts kindly, in a neat inversion of the misogynism echoing in the brand name. The breasts we see here are gently humorous: one pot majestically supports a head of broccoli like Atlas holding up the night sky; several others queue up on an IKEA shelving unit while the artist’s cat pouts in the foreground. What’s more – soberingly – striking, however, is their realism: Low makes black, brown and white pots, and sometimes pots with vitiligo. She makes pots that lactate. Pots that sport nipple rings and tattoos. Her pots have silver and gold stretch marks, moles, hairs; they are uneven, large, small; they bear mastectomy scars.

For the most part, people who have breasts mainly see them either by looking down at themselves when they’re in the shower, or perhaps in a bathroom mirror. ‘Pot Yer Tits Away Luv’ reflects this. It makes art out of naked female bodies but, turning the Guerilla Girls’ complaint on its head, this art isn’t intended to be ogled at in somewhere like the Met.. Most people who interact with Low’s pots will only ever do so via her Instagram account. Also notable: they do so as visitors to an exhibition rather than a gallery. The profile is itself part of the art: Low isn’t just a ceramicist profiting from making expensive naked sculptures, but a potter who focuses on contextualising female bodies in a space of self-ease. Some of the photographs are taken by Low herself, but many come from customers who’ve bought pots and placed them in their homes. The point isn’t to sip champagne and intellectualise stretch marks and nipple hair because now they’re suddenly on a plinth in an otherwise empty room: Low’s work compels us to see bodies on a windowsill or mantlepiece, or held up in front of somebody’s rhododendrons – normal, comfortable bodies that are in the private sphere, and know that they’re worthy of admiration.

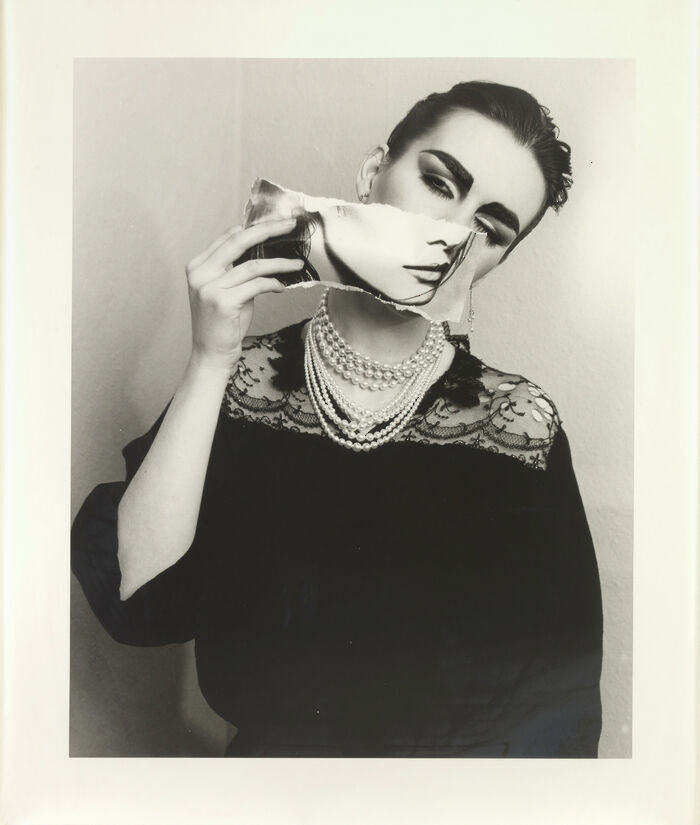

‘Women are a very recent invention,’ Ursula Le Guin observed in her essay Introducing Myself. ‘Women have been invented several times in widely varying localities, but the inventors just didn’t know how to sell the product. Their distribution techniques were rudimentary and their market research was nil, and so of course the concept just didn’t get off the ground.’ Who’s been inventing women? The male artists in the Met., perhaps. We have a solid cultural precedent for attributing to men the creation of women: Pygmalion in Ovid’s Metamorphoses whiles away the hours by chipping at an ivory Galatea; John Mayer, as recently as 2003, won a Grammy for making a disturbingly big deal out of his partner’s ‘porcelain’ skin in ‘Your Body is a Wonderland.’ Society appears to be rather attracted to thinking about women as sculptures or pieces of art: art is malleable. The artist can pick the shape and colour according to his own personal taste.

Women have not, historically, been the artists of their own bodies, although they have had a devolved role in decoration. One might here refer back to the 18th and 19th centuries, when ‘handicrafts’ were in vogue, and women were being encouraged to produce vast quantities of needlework and gilding and cutting and sticking, so that they might be surrounded by nice objects as they sat indoors all day. Rozsika Parker phrases it well: ‘when women embroider, it is not seen as art, but entirely as the expression of femininity.’ Women engaged in potichomanie (decorating pots with painted images), not pottery. They prettified rather than produced. They were asked to articulate a peripheral womanhood of neat stitches and good colour schemes that would coordinate well with the physical womanhood designed by men, which, if one is still struggling to envisage how this actually manifested itself, can be seen in the whalebone corset. Perhaps it is only to be expected that we would be more familiar with the shape of a bikini shot glass than a pot depicting actual breasts.

When we acknowledge the historic and largely persistent social role of women in unpaid domestic labour, we also have to acknowledge the aggressive prescriptive nature of the home environment, and the message it sends out: women’s bodies belongs indoors, but women’s bodies are not good enough to be indoors. They are the wrong shape; they are the wrong colour. They have the wrong parts. Oppression has long been cemented in our material culture, and it doesn’t take much rooting around to find objects and images on sale that surround the individual with reductive representations of what a woman is. An idle search for ‘woman statue home’ on Google will throw up ‘Western Sexy Slave Nude Girl’ as well as ‘Exotic African Tribal Woman’ and ‘Fat Yoga Lady Thai Metal Handcrafted Home Decor.’

Low is part of a new movement of intersectional feminist art that is taking ownership of the process of ‘invention’ through dealing with bodies and nudity: she recently collaborated on a pair of earrings with Lou Clarke, who makes laser-cut jewellery often featuring stubbly legs; there’s also Kenesha Sneed or ‘Tactile Matter’, who uses a wide range of mediums to depict women of colour; Liv & Dom, a pair of ceramicists who make nude incense holders and coasters; and Lou Foley, the artist behind ‘Are We Nearly Bare Yet’, where the naked bodies of a diverse range of self-identifying women are illustrated in a bright, bubblegum palette. We are finally able to appreciate a kaleidoscope of different bodies celebrated positively as ‘art’, rather than fetishised or omitted altogether from the what we see as womanhood. They are material evidence that when women get to define what women are, when women become the inventors, it becomes much easier to market womanhood as an inclusive gender, as well as a muse for friendly anatomical ceramics and earrings.

People will always get different things out of a business that creates nude pots. When I was researching this article, I kept coming back to a particular post from April where Low addresses the fact that in spite of her efforts to build an inclusive brand, pots depicting women of colour are the last to sell from her wholesale orders and the last ones standing on her website. “I understand that people are looking for a pot that maybe represents themselves in a physical way but this isn’t isn’t this about being valid regardless of the body we are in?” As a white cisgender woman – like Low – I do have to accept that if my stretch marks aren’t exactly well-represented, my general shape and colour is. Of course there’s a reason why I might be particularly drawn to a white tit pot with metallic stars painted on it, but there is little point in Low celebrating the diverse bodies if the kind that are most conformist continue to be prized above all others. Her brand should be celebrated not because it lets every buyer find a mini-me, but because it demands that people re-evaluate their idea of beauty.

Low’s pots take the reality of the female body and ask the environment to work around it: she offers women in a state of repose and neutrality. Her pots don’t have shoulders, but if they did they would be relaxed. ‘No need to hurry. No need to sparkle. No need to be anybody but oneself,’ as Virginia Woolf once wrote. Radical: a woman in a room without it altering her. Why go through all the stress of being naked in the Met.?

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025