School poetry anthologies: despised, adored, and often ignored : review

Following Julie Blake’s talk at the UL, Emma Morgan explores how anthologies can be so much more than just a vessel for education

My GCSE English class was clearly divided into two factions: the Enthusiasts, who would spend hours lovingly tweaking a turn of phrase in the hope of gaining an A*, and the Can’t-be-bothereds: a group of boys, their shirts streaked with mud from lunch-time’s football match, who sat at the back rolling their eyes and putting in the bare minimum of effort. The difference between us had been felt from the outset, but was made all the more obvious when we were presented with the anthology that we would have to study for our poetry exam.

“Whether we had adored or despised our anthologies, after the end of our exams, we all promptly forgot about them leaving them to gather dust in a box or drawer somewhere, or simply chucking them in the bin with a satisfied smirk before moving on to more important things.”

Already an avid collector of books, and perhaps the most enthusiastic of the Enthusiasts, I remember being quite excited that this anthology would be mine to keep, to scribble in, and to revisit whenever I wanted. I felt cultured and intellectual; I was the proud owner of a collection of poetry – albeit a mass-produced, A4 paperback which had been doled out to every GCSE student across the country. I began cramming the margins with annotations and thoughts, scrabbling to draw meaning from even the most straightforward of images, or the most coincidental of alliterations. I was so eager to add my own slant to each text that I would write any old thing, my jottings swinging between the glaringly obvious and the most far-fetched of untruths. But this didn’t really matter because all the while I was discovering the joy of poetry, the creativity of its forms, and the inexhaustible plurality of its meanings. For me, the great thing about the anthology, and about all school anthologies, was its careful selection of pieces that spanned a range of styles and periods, from the rotund Victorian patriotism of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, to the more recognisable themes of the Pakistani-born 21st century poet Imtiaz Dharker.

While I may have loved our GCSE anthology, behind me discontent raced through the Can’t-be-bothered ranks. To them, the poems – or perhaps the way in which they were taught to us – were pretentious, flat and boring. While my annotations extended in rambling streams of consciousness down the page, theirs consisted of single words, which, as if with a great sigh, dutifully identified the exam board’s favourite buzzwords: “enjambment”, “personification” and “metaphor”. Having failed to inspire them, poetry simply became a way of passing the exam, and so my classmates approached it in a box-ticking fashion, too impatient or uninterested to really discover the breadth and depth of meaning that lay before them.

“While on the one hand, the anthologies demonstrate to us the attitudes of a nation, they also reveal the little daydreams and conversations of individual children.”

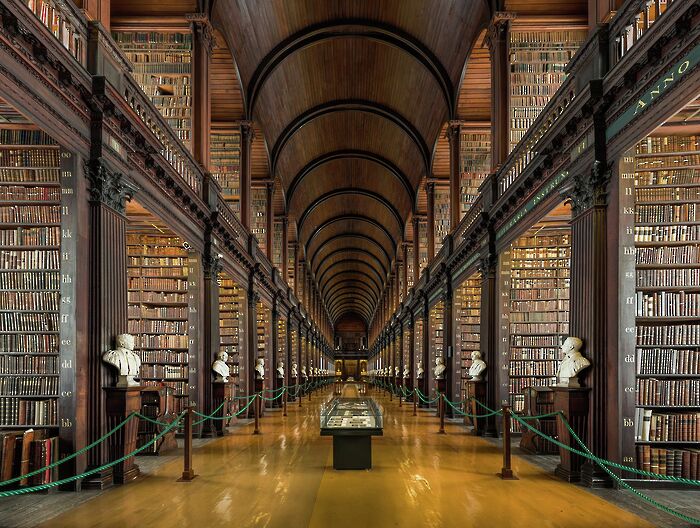

Whether we had adored or despised our anthologies, after the end of our exams, we all promptly forgot about them leaving them to gather dust in a box or drawer somewhere, or simply chucking them in the bin with a satisfied smirk before moving on to more important things. Having tucked my school anthology away in memories of a pre-university life, I was surprised to have it pulled to the forefront of my mind by the title of PhD student Julie Blake’s talk and exhibition School Poetry Anthologies: despised, adored and often ignored, at the University Library. Did Cambridge’s UL , almost buckling under the weight of its many millions of rare and precious volumes, really have time to be taking an interest in poetry books created to help children pass school exams?

I went along to find out.

In a little room in the basement of the UL, stood Julie and her huge collection of children’s poetry anthologies, some pristine with beautiful front covers, others, well-thumbed and containing library stamps from an academy in Hampshire or a secondary school in Ashton-under-Lyne. In many of the contents pages nestled those familiar, kneejerk names: Shakespeare, Rossetti, Larkin, Carol Ann Duffy. However, there were also anthologies of Caribbean poetry, or poetry written by immigrant children, sharing their experience of arrival into British life. Faced with such a varied and rich array of books, it came as little surprise to hear that Julie reached the final of the UL’s Rose Book-Collecting Prize. The care that she had put into piecing together her collection made me realise that there might actually be a lot more to say about the anthology that I had forgotten so easily. In her talk, Julie developed this idea, discussing the diversity of her collection and how its gradual evolution of selections and themes may actually tell us a great deal about the changing face of British childhood, education and society in general. She explained that, a few decades ago, anthologies largely focused on the great, white, male poets, Christopher Marlowe and his The Passionate Shepherd to his Love (1559) being a prime example. However, more recently, this poem has been included in collections alongside Maya Angelou’s Come and be my Baby (2014). Although they exist in contexts completely alien from one another, these works share a similar sound and message, and the fact that contemporary anthologies have paired the voice of a long-dead Englishman with that of a modern African-American woman reflects a possible globalisation, a move towards an equalisation of perspectives.

While on the one hand, the anthologies demonstrate to us the attitudes of a nation, they also reveal the little daydreams and conversations of individual children. Several of the books in Julie’s collection had been annotated by their previous owners, and it was possible to hunt through them (as if for hidden treasure), in search of a little comment here, a doodle there. She showed us one example, where two London schoolboys, Mark French and Terry Rush, had imperiously written “personification.”, continuing with the rather less academic explanation: “a street cannot be surprised, ‘cos it don’t live.”. Seeing these little notes helped me to imagine these two matter-of-fact boys, frowning at the poem before them as their teacher intoned the definition of personification in the background. I loved how that anthology had preserved traces of the people that had seen and touched it; it seemed to me a special artefact, a palimpsest of impressions and thoughts. I saw then that school poetry collections, in their wealth of perspectives and voices, which journey through the scribbling hands of so many different children, have a unique value that Julie is very right to celebrate. As she so thoughtfully put it, these little books provide access to a “conversation across time”.

A small exhibition of some of the earliest published children’s anthologies, including Richard Tottel’s Songes and Sonnettes (1557), can be seen in the UL’s entrance hall until 2nd February. You can also read Julie’s blog post on the subject here.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025