A 43 year old story about rice

Sheren Mao sits down with business-owners Mr. and Mrs. Wong to discuss how increasing gentrification is affecting the traditional rice industry of Hong Kong

I n 1973, Mr. and Mrs. Wong began running their rice business, selling cooking necessities and making rice deliveries around the neighbourhood. But due to the area’s gentrification, their shop has now closed down – and it's not the only one. Hong Kong’s traditional rice industry is all but dead.

“To put what we sell into simple words, it is the seven daily essentials in the Chinese tradition: coal, rice, oil, salt, sauce, vinegar and tea – but rice is our main product,” Mrs. Wong explained. As she excitedly introduced the various staples neatly laid out on the wooden-plank shelves, I couldn’t help glancing over to a rusty machine sitting quietly at the far end of the shop. Let me tell you, at first glance you really wouldn’t think it was operational.

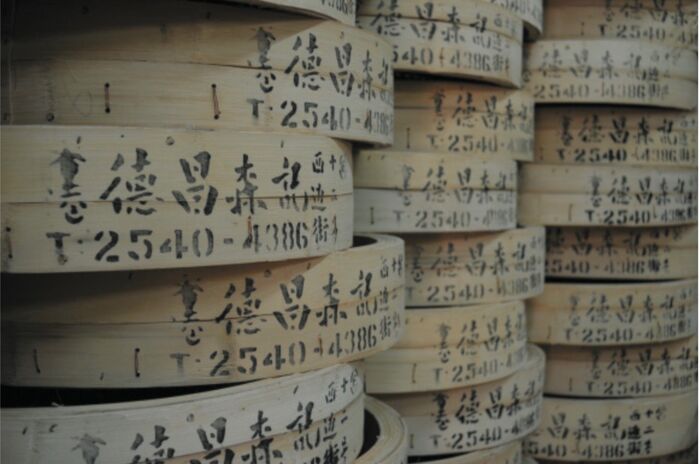

“What is that?” I pointed to the machine. With a soft smile, Mrs. Wong reached for a shallow, woven bamboo basket and dipped it into a bag of rice, scooped out a handful of rice and poured it into the top of the machine. She turned it on and a fanning sound filled the quiet shop. After a while, rice started coming out of the machine from two spouts, one positioned over a red bucket, the other over a blue bucket.

“You see, there is a specific procedure we must follow before we sell our rice. Firstly, by pouring it into this machine, we are filtering it and separating the clean rice from the dirty rice. Then, we pour the dirty rice into the machine again until it is cleaned. This is a really important step to ensure we give our customers the best quality rice. After the filtering is done, the rice is ready to sell, but some customers may want an order of medium-ranged textured rice.”

I looked at Mrs. Wong, puzzled by what she meant.

Seeing my confusion, Mrs. Wong chuckled and went on to recount the early days of this business. “Unlike what most people may think, there is actually a lot more to the technicalities of rice. My husband and I started by only selling glutinous rice [which has a sticker texture] and white rice [which is the most common form of rice we eat today]. White rice can then be further separated into 'new' and 'old' types. New rice is whiter and has a softer texture, while old rice is more yellow and hard.

“Some customers prefer one type of white rice over the other, and others like a mix of the two – it’s really just a matter of personal preference, but we do our best to give our customers what they want. So when customers come and order medium-ranged textured rice, this means they want a mix of the two. To do this, we toss new and old rice together in this large bamboo sieve for them – like this.” Mrs. Wong swiftly scooped the two types of rice into the sieve and skilfully combined the grains. Her precise movements told me that this was a skill that she had mastered over decades.

We moved from the back of the shop to the front, where countless bags of various types of rice were laid out. A white plaque was planted in each bag, with red words indicating the type of rice and its cost. “We ensure our rice is the best quality and set the prices fairly, according to people’s financial abilities within this area. Back then, one catty [around 600g] used to be HKD$1.50, but it costs HKD$7.00 today.”

As she spoke, a bell rang and Mrs. Wong turned her head towards the main street outside the shop and waved. It was Mr. Wong, who had just loaded a bag of rice onto his bicycle and was about to depart for a delivery. “We mainly serve people, restaurants and food stalls in the neighbourhood, but customers from faraway places too. We supply The Hong Kong Society for the Blind twice a week. If an order exceeds twenty catties, we provide delivery services where my husband will deliver them on his bicycle. He has been using the same bicycle since the day we started.”

When I asked her about the future prospects of her business, I was rather surprised at Mrs. Wong’s phlegmatic reply. “I am in my 60’s and my husband is in his 70’s. We are so old that there are no other work opportunities left for us. This will be our last working year. Besides, once the new residential area across the road is completed, all these neighbouring stores will be forced to vacate, so that this site can be demolished. There is not much to dwell on. Our business has already been severely affected by the convenience of supermarkets.”

Despite the tough exterior that Mrs. Wong put on, I was still saddened by her reaction. It was as if she has already accepted the inevitability of her business's demise and had detached herself from the emotional ties and customer relationships that came with her work.

She added, “You know, sometimes it’s amusing to think about how there used to be more rice shops than bank branches, but today, our society simply sees no value in this industry anymore.”

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025 News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025

News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025 News / Caius clock hand returned nearly 100 years after student prank31 March 2025

News / Caius clock hand returned nearly 100 years after student prank31 March 2025 News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025

News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025 News / Write for Varsity this Easter31 March 2025

News / Write for Varsity this Easter31 March 2025