Duchamp to Dat Boi: The 21st-century rebirth of Dadaism

Teddy Mack takes a look at the forgotten roots of meme culture and contemporary media as a reaction to a nonsensical world.

In the world's most celebrated Renaissance portrait the subject sits confident and serene, arms gently folded, waves of brown hair parted in the centre, penetrating eyes seeming to follow you around the room, top lip adorned with that most iconic moustache. I'm talking, of course, about The Mona Swanson (2013) by Tumblr user RAOqwerty, which superimposes the face of Ron Swanson from Parks and Recreation onto Da Vinci's magnum opus.

Reading the above description, one would be forgiven for thinking not of the Mona Swanson but a similar, yet somewhat more critically acclaimed, piece known by the moniker L.H.O.O.Q – or, to the uninitiated, Mona Lisa with Moustache. This 1919 masterpiece by French artist Marcel Duchamp is part of the Dada movement, a wholesale rejection of traditional artistic values and a giant middle-finger to the world that created them. And now, through our memes and online art, we are giving the world that same middle-finger once again.

Dada, or Dadaism, emerged during the early twentieth century as a reaction to the horrors and atrocities of World War I. Artists could no longer bear to uphold the values of such a society, and instead embraced the abstract, the surreal and the downright nonsensical.

Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q pokes fun at traditional art by adorning a mass-produced postcard of Da Vinci's Mona Lisa – or La Joconde as she is known in France – with the classic moustache-and-goatee combo. The work's title ‘L.H.O.O.Q’ is pronounced like the French slang phrase 'elle a chaud au cul', a crude description of female arousal; Duchamp juxtaposes the vulgarity with his visual play on 'Jocondisme', a widespread trend among the French elite that had made a something of a cult object out of the Mona Lisa.

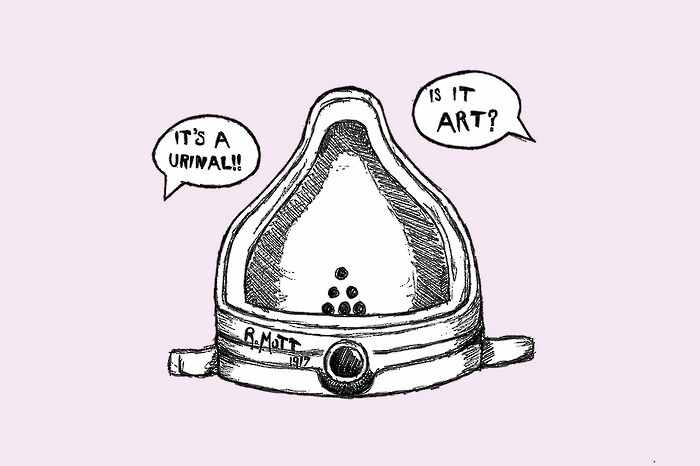

Duchamp's is also known for a porcelain urinal, tipped onto its back and given the title Fountain as well as a cryptic signature by the mysterious ‘R. Mutt, 1917’; philosopher Steven Hicks interprets its meaning as art being something you piss on. In 20th-century Dada, art had to be fought with art, a full-scale assault on the disastrously elitist system that had not just governed aesthetics but plunged the world into violent conflict.

The truth is there aren't always goodies and baddies; things don't always make sense or happen for a reason

Today it seems that very little has changed. The internet developed in a world of terror attacks and the War on Terror; seemingly endless mass shootings; Trump and Kim Jong-Un’s nuclear stand-off; the rise of nationalism. Hell, even Nazis are back somehow. Our generation’s response to these horrors? Dada: creepypasta, shitposting, doge. Memes.

“Don't be ridiculous,” you say, “memes are just internet fads with a shorter shelf-life than an open pot of houmous”. But memes have evolved well past the days of lolcats, troll face, philosoraptor and so on. The formula of memes as reactions has been burnt, and with it their internal governing logic.

‘Dat boi’ for example, started life as a photoshopped image identifying a young boy, ‘Dat Boi’, as the “most wanted criminal arrested”. The meme went through several iterations up to May 2016, when it settled on the form of a green frog riding a unicycle, and the words ‘here come dat boi / o shit waddup’ recited by text-to-speech to the tune of Crank That (Soulja Boy). As of May 2019 the video has been viewed more than 12 million times.

The same trend towards the absurd can be seen in other types of visual media: take the early popularity of web-series Llamas with Hats, ASDFmovie and Don’t Hug Me I’m Scared, and now with TV shows like Rick and Morty, Bojack Horseman or Donald Glover's award-winning Atlanta. Each is set in a world like ours, but pushed beyond the extreme. They use the surreal to explore themes of what it means to be an adult in the world: unemployment, depression, racism, nihilism. They allow us to escape the madness of our own reality and take refuge in a place of even greater nonsense, where we are comforted at least by the thought that at least our lives aren't that bad.

But how can we explain why we find these things entertaining? What is it that makes ‘Dat Boi’, Shooting Stars or that picture of the black hole so funny? The fact is that there is no joke. There is no deeper meaning. No hidden alternative interpretation or necessary insider knowledge.

We have been conditioned by film and television to think that in life the goodies win and the baddies lose, that life is a great mystery and it just takes one person to make everything fall into place. But the truth is there aren't always goodies and baddies; things don't always make sense or happen for a reason. So if the world doesn't make sense, why should anything else? This is the heart of Dada. As said French painter Francis Picabia: “Dada is like your hopes: nothing.”

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025

Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025

News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025