The Mays XXVII is a record of the here and now

Helen Grant looks at this year’s “charming and complicated” edition of The Mays, guest edited by Louis de Bernières and Mary Jean Chan

Content Note: this article contains extensive discussion of sexual violence in relation to some of the subject matter of the anthology.

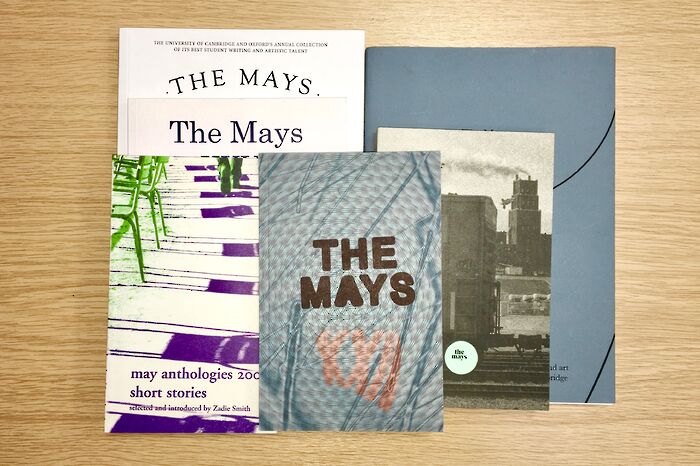

At a time when the internet has accelerated and democratised how we publish creative work, student anthologies ought to be history. The Mays, now in its 27th year, hasn’t so much as blinked. Some of its confidence comes from sheer cumulative gravitas – spotting Zadie Smith in 1997, being guest edited by figures ranging from Ted Hughes to Philip Pullman and Ali Smith – but the rest comes from something deeper, a belief in the value of an annual physical compilation of poetry, prose and art.

Humans like tradition, and they also like cycles. This year’s Mays editors Elizabeth Huang and Eimear Ní Chathail have accommodated the shift towards the digital by creating an online supplement for audio-visual art, but for the most part it will be possible to lay out previous volumes side-by-side, and see that they have fundamentally remained the same. Being published in The Mays does more than simply putting your work out there, when poems could fit into an Instagram post and sculptures could be displayed at full size at an exhibition. The Mays offers instead a crucial microcosm and micro-generation that are intimate and tactile. Volume 27 will offer the reader something different from what it could have done a year ago or five.

It can be difficult to write about violence in a way that is truthful but separate from the voyeurism that persists in modern culture; Fisher does it brilliantly.

Three pieces this year deal with sexual violence, reflecting the broader fall-out from 2017’s Me Too and Time’s Up awakening. ‘After’ by Joanna Kaye, probably the most uncomfortable to read, makes a devastating use of parallel columns and empty space to compare the emotional and practical consequences for a rapist and a survivor. Valk Fisher’s ‘Connective Tissue’ responds to the September 2018 Brett Kavanaugh hearing, and deals with questions of how to disclose trauma by evoking physical wounds. ‘Freedom 2.0’ by Elle Lavoix considers a world where ‘liberated’ sexual spaces remain predatorial. As in ‘Connective Tissue’, the reader is directly addressed in the second person: Me Too, you too. Some of the tonal shifts echo those of the viral New Yorker story Cat Person; conversations that feel like the blade of a kitchen knife suddenly cutting into your own fingers.

In ‘Connective Tissue’ flesh and meat are used to articulate fury, and visceral language keeps the injustice done to Christine Blasey Ford open to us all like a new wound: ‘Miss Piggy bleeding badly, blood coming out of her wherever … Your innermost parts come undone with the season, cooked inside like pulled pork.’ It can be difficult to write about violence in a way that is truthful but separate from the voyeurism that persists in modern culture; Fisher does it brilliantly.

Guest editor Louis de Bernières rightly uses his foreword to draw attention to Katherine Robinson’s prose piece ‘Stranding’, which explores a bloody flensing, perhaps in response to Japan’s recent decision to restore the practice of whaling: ‘If she forced images to remain unconnected to thoughts, then red was a colour ... She had not seen anything this bright all winter.’ ‘Stranding’ explores the tension between the grim corporeality of death and our desire to find dignity in it. Meanwhile Ben Vince’s ‘oh boy mother i am such a catch’ uses whale flesh and blubber to understand the narrator’s own body and impulses – ‘the japanese have started harpooning again / but no, darling, why don’t we just sit here sucking / on each other’s blowholes?’ – while Mary Gatenby’s fabric sculpture ‘The Whale’ depicts agony unravelled. If Robinson captures stillness, Gatenby confronts all that is frantic about the moments just before the end.

Many of the writers and artists who end up submitting to The Mays are probably also the kind who will at some point try dissolving three teaspoonfuls of instant coffee straight into their tongues

The Mays XXVII is not gloomy. It is soaked through with exquisite beauty – Kwann-Ann Tan’s description of ‘days passing like soap bubbles popping in the heat’ in ‘Muar 1941’ is, I think, my favourite line in the entire anthology, quietly affectionate for a time and a place even when capturing one of humanity’s darkest hours. Some of the writing and art is actively joyful: Jenny O’Sullivan’s piece ‘Lightbulb Moment’ is radiant in form and content; Vida Adamczewski’s poem ‘Magpies’ over brims with adoration for birds that ‘stick together like book clubs’; Alisa Santikarn creates waves and geodes out of vibrant turquoise in ‘Untitled #1 and #2’; Walter Jones’ ‘Bruce Lee’ extract could easily expand into a gloriously 70s novel; Zoë Matt-Williams’ ‘Portrait of an Artist as a Young Woman’ tantalises like an illustration glimpsed in somebody else’s book.

We are seduced by the idea that Oxbridge societies are an ongoing gold rush of talent. The Mays has become to student writing and artwork what the Footlights is to student comedy; stare hard at the title page and you half expect to see indentations from Zadie Smith’s book deal. It feels important therefore to mention ‘I climbed the Castle Mound’ by Sarah Brady, alternatively titled ‘Disillusionment’. Many of the writers and artists who end up submitting to The Mays are probably also, as Brady describes, the kinds of students who will at some point try dissolving three teaspoonfuls of instant coffee straight into their tongues. Brady’s piece is clever, funny, and deeply reassuring about a common humanity among us all.

In February, Huang and Chathail described The Mays as a ‘record’ of the year’s student writing and art. Volume 27 is charming and complicated, and some of the pieces inside are bewildering, or painful to read. But one day it will be a reminder of what it was like, being this age in this place at this time.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026