Siddhartha: Hesse’s guide to a meaningful self-isolation

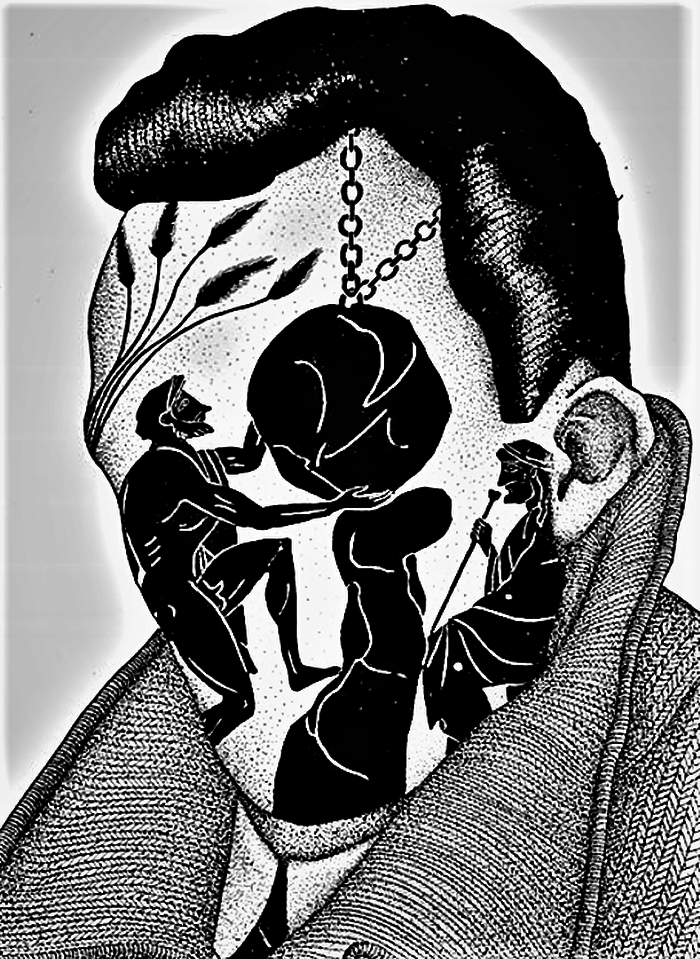

Herman Hesse’s proposal of life through self-discovery in Siddhartha is appealing, yet somewhat problematic, Andreas Charidemou writes.

Content Note: This article contains brief mention of suicide.

‘Your soul is the whole world,’ Siddhartha pondered before he began his journey of self-discovery.

Quarantined at home after leaving Cambridge, still shocked by the abrupt end of my second year, I felt rather disillusioned. I sought a read to take my mind off things. My brother recommended Siddhartha; a surprisingly fitting classic by Herman Hesse, which earned him the Nobel Prize in 1946. It takes place in India, and follows the spiritual journey of a young man in the age of Buddha (who cleverly shares his first name), as he attempts to discover a higher state of being, or “Weltanschauung” of a philosophy of life. The book is short, the prose beautifully written.

The problem does not lie in finding perfection but instead in achieving completion.

Siddhartha begins his life as a Brahmin’s son, and is on his way to become a promising Hindu priest. However, one day he realizes that his soul has been left unsatisfied by his devotion to duty and religion. He is at a dead end, and leaves home to become Samana, an ascetic monk. By experiencing the extremes of deprivation, he hopes to empty himself completely of all physical desires in order to hear his soul and find peace. This brings him no closer to happiness. He’s reluctantly convinced by his companion Govinda to go and hear the teachings of Gotama Buddha, a man who was said to have achieved the blissful state of Nirvana they are seeking. In one of the book's most iconic passages, Siddhartha encounters and converses with Buddha, then spurns him. After meeting the best teacher the world has to offer, it becomes clear to him that the way of salvation cannot be taught, that words are empty sounds, and that each man must find his own way.

The autobiographical elements of the story are thinly concealed. As young man, Hesse himself rebelled against the orthodoxy of his parents. A firm believer in self-education, he rejected their strict religious beliefs and ran away to shape his own life. This aligns with the main truth highlighted by the book, which appears to be the impossibility of achieving enlightenment or Nirvana through learning and religion; it is made clear that this can only be reached through self-reliance. This work, alongside Hesse's other novels, were considered the literary gateway drugs of the youth of the 1960s and 1970s, primary symbols of the counterculture. In the wake of two World Wars, the possibility of asserting the meaning of life appealed to many.

Searching for meaning in life through self-discovery and distilling wisdom from experience are wise occupations for the solitary weeks ahead.

In the second part of the book, Siddhartha experiences the material world. As a merchant, he experiences the heights of opulence and becomes the lover of the enchanting courtesan Kamala. Worldly affairs gradually enslave him, making him feel more lost than ever. He abandons everything and is close to committing suicide by drowning in a river, when the mysterious word “OM”, a Hindu word signifying the essence of the ultimate reality, comes to his mind. Following this revelation, he becomes a ferryman and devotes his life to understanding the secret of the river. The secret appears to be that the concept of time does not exist. The river has no past, no future, no beginning, no end: it is merely present. The protagonist discovers that happiness is real only when causality or time ceases to exist for him. The problem does not lie in finding perfection but instead in achieving completion.

However, one cannot help but feel frustrated with the inherent arrogance and selfishness attached to the individualistic philosophy of life that Hesse advocates. In order to reach enlightenment, Siddhartha must abandon society entirely, this including his companion and child. His attitude towards humanity is patronizing, belittling; he consistently refers to normal human beings as “children”. Hesse seems to suggest the fundamental incompatibility of living with people and being authentic, of forming bonds of friendships and remaining true to oneself.

This is a view that I find hard to accept. The parallels between this philosophical position and Hesse’s own failures as a father, husband and scholar during the rise of Nazism are blatant. Yet perhaps now, at a time when so many of us feel and are isolated against our will, Hesse's words in Siddhartha have a ring of truth. The idea that one should seek meaning in life through self-discovery, distilling wisdom from experience, is a wise suggestion for the solitary weeks ahead.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025