The Spirit of Shakespeare & Company

Tilda Butterworth reminisces about a distant summer, living in Paris’ most famous bookshop

The summer before beginning my degree at Cambridge, I was a tumbleweed at Shakespeare & Company, the famous English-language bookshop on the Left Bank in Paris. The requirements of being a tumbleweed are simple: read a book a day, help with opening and closing, work a two hour shift each day, lend a hand with weekly events, write a one page autobiography for the archive – and in return, you can sleep in the bookshop. Over 30,000 tumbleweeds have passed through since 1951 – according to its former proprietor, George Whitman, it is a “socialist utopia masquerading as a bookshop”.

I arrived in the middle of June 2019. Several long-term tumbleweeds had just left, so the three of us sleeping in the shop were entirely new to it all. We romanticised everything – the clattering of the typewriter in the street outside the window; the cryptic, longing love letters left in the books upstairs; Notre-Dame across the road, charred and clad in scaffolding. We went into raptures at the feeling of the cool tiles under our bare feet as we brushed our teeth around the miniscule sink in the library, and at the euphoric experience of falling asleep surrounded by walls of books. After a night spent drinking cheap wine by the Seine, or watching the buskers of Rue de la Bûcherie, we’d transform the sofas into beds, whispering goodnight to Aggie the cat and the portraits of writers above the staircase. I often tossed and turned for hours, feeling like electricity was running through my veins, certain that the spirits of long-departed tumbleweeds were watching over me.

Whitman referred to the bookshop as “a place where I can safely look upon the world’s horror and beauty”

Days passed with all the distortion of time in a dream. Throwing boxes down to the storeroom and lugging chairs up from the basement for the weekly readings, sweaty and exhausted. Helping with a storytelling workshop for children. Going to the laundrette or the creperie with a disintegrating paper bag full of coppers, after fishing euros out of the wishing well which reads ‘Feed the starving writers’. Listening to Leonard Cohen on the riverbank in the dark.

The weather was changeable, to say the least – Paris in summer feels like an alternative dimension. The bookshop was as humid as a greenhouse as tourists crowded into it. On my last night, there was a freak rainstorm which sent us running back to the shop through the empty streets of Paris, the pavements awash and the elements whirling around us. Whitman referred to the bookshop as “a place where I can safely look upon the world’s horror and beauty”, and that is what I felt that night, entering the sanctuary.

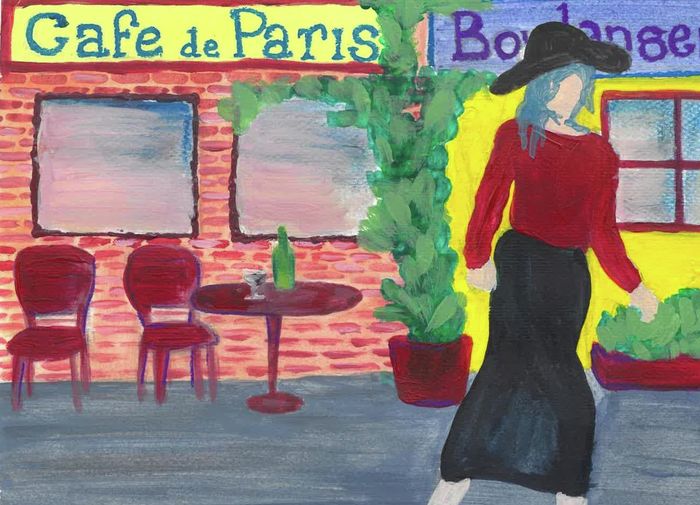

Shakespeare & Company is the favourite haunt of dreamers seeking soulmates and thus, a place of constant strange serendipity. There are those who stay for hours on end and those who simply pass through, their treads wearing away the tiled floor. Every morning, while setting up the café tables in the sunlight, we met tourists, flaneurs and vagabonds. Cradling enamel mugs of black coffee, we listened to their life stories. Then there were the overly chivalrous Americans with suitcases and the disillusioned foreign students, one of whom hit me on the head with a book in a (failed) effort to be flirtatious.

“Shakespeare & Company is the favourite haunt of dreamers seeking soulmates, and thus a place of constant strange serendipity.”

I couldn’t stop marveling at how present the literary world and its history felt within the walls of the bookshop. I read the works of James Baldwin and the diaries of Anaïs Nin while sleeping where they once did. On my first night, Deborah Levy (the writer-in-residence at the time, and mother of my childhood best friend) gave me a bottle of wine and a book of essays, to thank me for helping her with her suitcase the following morning. One of the many books I read while tumbleweeding was M Train by Patti Smith. I devoured it in only a few hours, full of awe and wonderment. The next day, Patti posted on Instagram that she had passed the shop on a nighttime walk. It felt as though we were in the right place at the right time, and that if we stayed we always would be.

As is evident from my experience during the fortnight I was there, tumbleweeding relies on communal living, and Shakespeare & Company relies on its readers. Since the pandemic struck in March, there has been an 80% decline in sales. France’s second national lockdown means that the bookshop and café (considered ‘non-essential’) will have to close again. Recently, the bookshop posted a plea to support them if you have the means, by purchasing books, gift cards and merchandise from the website.

It is heartbreaking that a place founded on kind-heartedness, generosity, trust and hospitality to strangers, has been hit so hard during this global crisis; the qualities it stands for should never be considered anything other than ‘essential’. The joy of Shakespeare & Company lies in its deep history of course, but also in those who inhabit it: strangers with whom one has fleeting, meaningful encounters, the booksellers, the tumbleweeds, the baristas in the café. It is an atmosphere of complete liberation and communality; a place of happenstance where anything can and will occur. It may be an uncertain time for the bookshop now, but in the words of Hemingway, “There is never any ending to Paris… We always returned to it no matter who we were or how it was changed or with what difficulties, or ease, it could be reached.”

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025

News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025 Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025

Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 News / Zero students expelled for sexual misconduct in 2024 25 April 2025

News / Zero students expelled for sexual misconduct in 2024 25 April 2025