5 history books you should read if you hate reading about history

A fool-proof list of history books you will actually find interesting

Isn’t it funny how the popular history books that top bestseller lists are oh-so-often the least readable? I’m talking barren accounts of dates after dates; slews of unfamiliar names and places which stumble into chapters like last-minute invitees. Short introductions have an irritating tendency to assume their target audience has already read another, better short introduction, while even the most talented historian will struggle to cram China’s entire history into 200 pages. God forbid, if your standard popular history stretches over the 500 page mark, you’d better start saying your prayers: buckle up to read about twice as many decisive events in just as little detail. It’s draining, reductive, and just plain dull. And it begs the question – why do these kinds of books keep selling?

“Popular history becomes more about dragging yourself through a book because it’s cultural capital, and much less about actually engaging with and enjoying the history in question”

Like many Cambridge students, I’m no stranger to imposter syndrome. That self-conscious voice that snakes itself around rational thought, whispering that you’re not smart enough, that you’re not academic enough. As a History undergraduate, I used to wonder why I hated reading pop history books in my own free time. I had this giddy, lofty idea in my head that a Historian (with a capital H) should settle down in a comfy armchair by a raging fire and be content to spend hours leafing through names of battles and the dates that they happened, effortlessly retaining information. The Important Events were the events which everyone older than me had learned about before, and that mostly meant a depressing amalgamation of politics and war. It’s downright pretentious, but I think it’s this kind of misconception that means popular history bestseller lists are dominated by the convoluted.

The things is, popular history books play a complicated game. They need to stay accessible to readers with no background in history, but also let them feel as if, by reading a history book, they’ve suddenly gained access to the exalted ranks of the intelligentsia. A lot of the time, this means the books are crammed with strings of dates – because, you know, that’s what History’s about, right? – with very little analysis or perceived superfluous detail about things like family life, culture, or women. Popular history becomes more about dragging yourself through a book because it’s cultural capital, and much less about actually engaging with and enjoying the history in question. It is this ego-boosting balancing act which has ruined so many popular history books for me. Nonetheless, by the same token, those history books which I have enjoyed stand out as proof that it isn’t that I hate reading about history, but just that I hate reading the wrong history books.

And so, without further ado, here are five of my favourite history books, especially recommended for people who think that they hate reading about history.

1) A Kim Jong-Il Production by Paul Fischer

It’s the 1970s, and North Korean dictator Kim Jong-Il is movie-mad. Really movie-mad. So movie-mad, in fact, that he kidnaps his favourite South Korean director and forces him to make films for the state for seven years. If that’s not enough, he also kidnaps the director’s ex-wife, forces the two of them to remarry, and has her star in many of the new movies. But Kim Jong-Il doesn’t realise that they’re plotting a daring escape to America.

A Kim Jong-Il Production is a really engaging, entertaining book about events so bizarre that they read like fiction. You’re spoon-fed a lot of information about the North Korean regime, their film industry, and their hushed-up record of kidnapping, so that you learn a lot but it never feels like work. However, this book does tend to fall into the trap of presenting life in North Korea as a show to be gawked at, which means that it doesn’t always stick to the most critical perspective.

2) 1913 by Florian Illies

I’ve come to realise that a lot of people already know this fact, but when I first read Florian Illies’ 1913 in the summer of year 12, I was shocked to learn that for one month of that titular year, Hitler, Stalin and Tito were living on the same street. 1913 is divided by month to follow the lives and careers of cultural figures as Europe geared up for WW1, and could perhaps be summarised as a book of early 20th century celebrity gossip. You can’t help but feel sorry for Kafka as he tries and fails at love! The writing style is very dreamy, so it all makes for easy and evocative reading.

3) Controlling Desires: Sexuality in Ancient Greece and Rome by Kirk Ormand

Controlling Desires was the first ‘academic’ history book that I can remember racing through. Although ostensibly about sexuality, everything is analysed through a cultural lens, so readers are also treated to some of the best Sappho fragments and Aristophanes excerpts. The chapter on visual arts and pottery is also surprisingly vivid, and includes an interlude explaining why it was a trend to decorate your home with windchimes in the shape of phalluses. This book completely altered my understanding of ancient gender and sexuality, and is the user-friendly, bona fide introduction that every topic needs its own equivalent to.

4) A Very English Scandal by John Preston

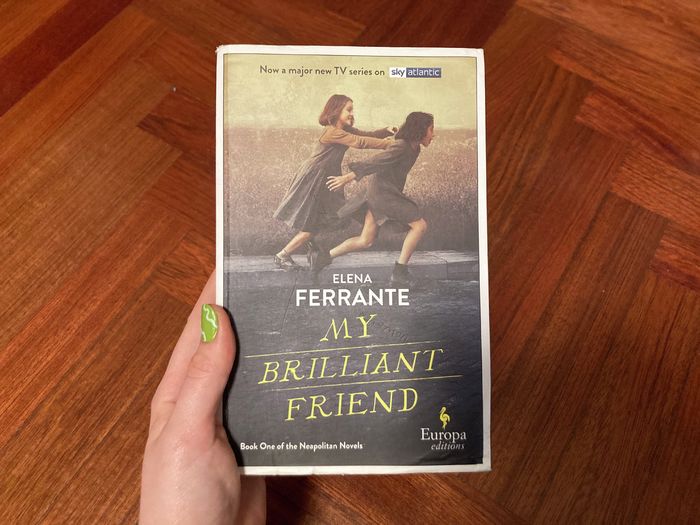

Galentine's Reading: My Brilliant Friend

You might have already come across A Very English Scandal in the form of the Golden Globe winning BBC drama, which aired as a three-part mini-series in 2018. Like the show, the original book is well worth your time: it focuses on the charismatic leader of the Liberal party, Jeremy Thorpe, who had a secret, illegal gay affair with an unstable model during the 1960s. After the couple broke things off, Thorpe enlisted his friends and colleagues in a plot to assassinate his ex-lover, fearing that revelations of his homosexuality could potentially ruin his political career. However, as things turned out, the scheme (sometimes humorously) did not go to plan, and the result was the revelation of a scandalous, sordid tale of blackmail, lies, and attempted murder. The book is written almost like a crime novel – with this in mind, however, note that Preston has taken some creative license in recreating key figures’ thoughts and emotions.

5) The Astronomer and the Witch by Ulinka Rublack

The Astronomer and the Witch is another recommendation that is probably better categorized as academic history than popular history (I first came across it on an essay reading list), but that doesn’t hinder its readability. The astronomer in question is none other than Johannes Kepler; the witch is his widowed mother, put on trial for witchcraft in 1615. Written vividly, Rublack narrates how Kepler risked his burgeoning career to conduct his mother’s defence in a tense and prolonged criminal trial, shining a light on a Lutheran Germany in the throes of scientific revolution, Reformation and witchcraft alike.

These are just a few historical recommendations that I personally found easily readable and engaging. If even these don’t hit the spot, the next best thing is probably well-researched historical fiction: I’d point to Maria McCann’s criminally underrated As Meat Loves Salt, or Hillary Mantel’s Wolf Hall…

But these are recommendations for another day, and another article.

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025

Theatre / We should be filming ADC productions31 December 2025