The paradox of the female muse

In her second column, Eleanor Antoniou explores contemporary artists’ attempts to reclaim the figure of the female muse

Female creators have long had a complicated relationship with the figure of the muse. In ancient Greek mythology, the nine Muses were goddesses who inspired the creation of the arts, literature, music, and sciences. This seems to suggest that they are meant to be active subjects, creators rather than crafted objects. And yet, when we think of a muse today, we most often picture a passive, reclining female model; she is powerless, perhaps nude, and posing silently in front of a man. Traditionally, a muse is always a woman, and the creator who uses her for his art is a man.

“Modern female artists are fighting back to reclaim her and to restore her creative power”

There is, then, a paradox at the heart of the concept of the muse. The notion of the ancient muses seems to enable female creativity: the muses are goddesses, who, in turn, inspire others to create art. However, as male writers and artists begin to shape their own creations, they also shape the muse herself. She becomes another part of their creation as they begin to appropriate her, so that our modern understanding of the muse is a passive and objectified woman. She is still an inspiration to the male creator, but inspires as a powerless object, as an emblem of idealised female beauty, rather than an active creator in her own right.

Even Sappho, the most famous female poet from antiquity, has been named as the tenth muse. In the passive understanding of the muse, this limits Sappho to an object for male writers to exploit. She becomes an object of poetry, rather than a poet. Indeed, it is Ovid’s version of Sappho that influences how so many people think of her today: the love-sick girl who threw herself off a rock to her doom, because of her overwhelming love for Phaeon. In her own poetry, Sappho presents women as subjects, and yet she herself has become a story and an object through history’s interpretation of her: the patriarchal myth surrounding her life all too often overlooks Sappho’s own subjective creativity.

Whilst male-dominated art history has moulded the muse into a powerless figure, modern female artists are fighting back to reclaim her and to restore her creative power: they are repositioning themselves as subjects and calling attention to the paradox of the subject/object dichotomy that has defined the muse throughout history.

In her self-portraits, Frida Kahlo creates herself as her own muse. She famously said, “I am my own muse. I am the subject I know best. The subject I want to know better.” Kahlo ascribes to herself a unique power, reclaiming her image and drawing creative inspiration from within herself.

“The male gaze is cancelled out here as women take the nude for themselves”

Yayoi Kusama does something similar by casting herself in her artwork as both subject and object. She becomes both the inspiration for the art but also the viewed image, inviting viewers to look at her body, sometimes nude, but always retaining her own power as creator of the image itself. Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Rooms further play upon the subject/object dichotomy, as those who walk through cannot photograph the art without themselves in the frame. We are irresistibly drawn to look at ourselves within the infinitely sparkling reflections, unable to separate ourselves as viewer of the art from the object that we are viewing. We become almost a part of the installation, adopting the position of a traditional muse, but always retaining our power to move freely and gaze at the piece as we desire.

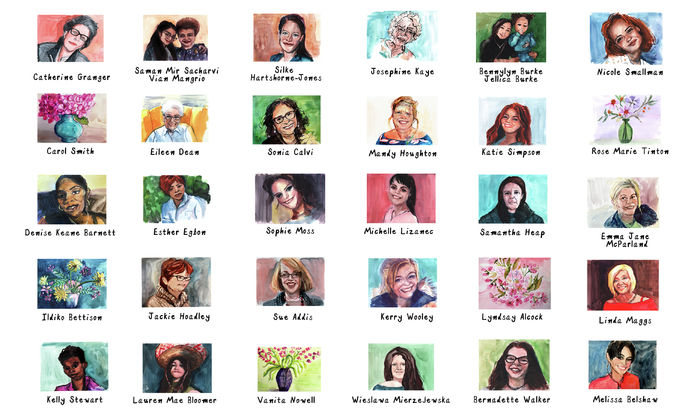

Today, it is perhaps the female nude above all which calls to mind images of the passive female muse posing for the male artist. But the beautiful watercolour paintings created by Blanca Schofield Legorburo on her Instagram page, Eve Taking a Nude, reclaim the female body and celebrate it. The male gaze is cancelled out here as women take the nude for themselves. The paintings are posted alongside the voices of each model, whose own words accompany each portrait, in stark contrast to the silenced women who have modelled for male artists throughout history.

Finally, last term, the New Hall Art Collection at Murray Edwards pushed against the boundaries and paradoxes surrounding the modern muse through their exhibition, The Centre of the Frame, which displayed Maud Sulter’s series of the nine Greek muses recast as Black women, calling out the Westernised beauty standards with which the muse has been burdened. Crucially, Sulter’s women all retain a sense of agency, and Sulter herself appears as one of the muses, Calliope. She places herself inside the frame, appearing as an equal alongside her other models, each accompanied by Sulter’s own poetry: she is both the artist and the muse here. In this way, the muse’s original creative power is finally restored through the works of women artists, and the objectified and patriarchal muse figure vanishes through the art of reclamation.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025