Irvine Welsh’s punk poetics

Tommy Gilhooly explores the work of punk writer Irvine Welsh and his revolt against the traditional novel

Who said punk was dead? Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting is notorious for its portrayal of heroin, bar fights, psychopaths, grimy criminality, and benefits fraud. Oh — and who can forget the ceiling-crawling, somehow-talking, dead baby. It is perhaps the defining novel of punk literature, and it steals the award as the most shoplifted book in Britain. Welsh’s writing — with its raw Scots dialect, disjointed typography, and fragmentary narratives – crafts a punk poetics that affronts and abrades the safe, bourgeois, ‘Standard English’ novel which dominates contemporary British literature.

“In Welsh’s writing, the text itself is political”

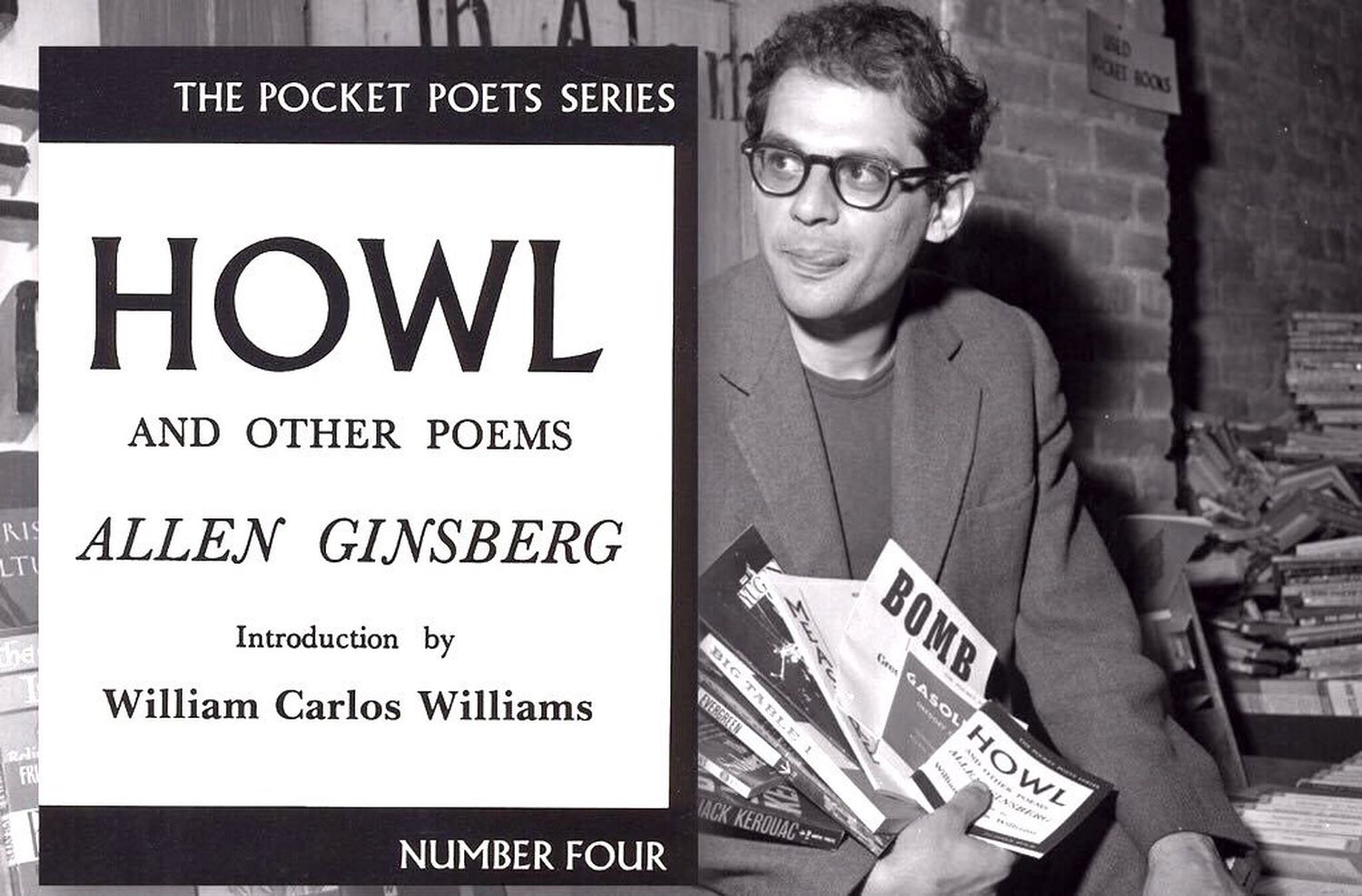

Key to Welsh’s work is the figure of ‘the junkie’. Its genealogy lies in the 50s Beat Generation. Alexander Trocchi — the ‘Scottish Camus’ — was a massive influence on Welsh. Rebel Inc, the countercultural printing house of Alba, published Trocchi’s mostly forgotten post-war novels. Trocchi utilised the addict figure to gain an outsider’s perspective on society — a stranger morally, intellectually, and narratively. Trocchi was an addict author too, selling a few pages of his Cain’s Book to his publisher in regular instalments, to get his next hit of heroin. In Welsh’s development, the addict figure has the misfit perspective on the fallout of Thatcherism in a post-industrial Scotland. Welsh’s main preoccupation in Trainspotting seems to be in locating the place of a proletarian youth in this political and economic new order, an era of deindustrialisation where Welsh saw drug addiction replace traditional manual labour.

In Welsh’s writing, the text itself is political. The raw Scots dialect and colloquialism he uses grind against the Standard English language ubiquitous in contemporary British literature; it grazes the PR accents of audiobooks. Welsh’s choice to employ such language is more than just scene-setting. It harks back to medieval Scottish literature, to the ‘makars’ Henryson and Dunbar, who, from a distinctive Scots language, derived a distinctive literary voice. Welsh wanted Danny Boyle’s immortalising film adaptation of Trainspotting (1996) to carry harder Leith accents, even more than the novel, so the ‘spoiled middle-class brats who want to shop around for their next culture fix’ would find it all the more impenetrable. For all of Welsh’s abrasive tone, he establishes a nuanced dissection of the connection between language, knowledge, and power.

Another component of Welsh’s poetics is pertinent here. As Alice Ferrebe notes, Welsh is more acquainted with, and influenced by, music lyrics and soap operas than ‘the classics’. Think EastEnders rather than Virgil or Iggy Pop instead of Homer. With the mystification of certain areas of knowledge — locking particular people out with dead languages and snobbish flippancy — so too can Welsh forge his own interpretability. Welsh locks in the knowledge and enjoyment of the underclasses’ narratives through his own linguistic decisions.

“He establishes a nuanced dissection of the connection between language, knowledge, and power”

The idea of a ‘main character’s journey’ — be it romantic, intellectual, moral, or financial — is what we expect, as consumers, when we walk into Waterstones to buy a novel. Welsh’s narrative construction displaces any sense of a journey, linearity, or progression. With Welsh we are continuously, sporadically flying around different characters. The breaks within Trainspotting can hardly be called chapters; instead they are episodic. This erasure of a protagonist’s journey is Welsh’s ultimate, punkish denial of progress which serves as the framework for the standard, bourgeois novel of contemporary British literature. It is reminiscent of the Sex Pistol’s wailing end to ‘God Save the Queen’: ‘no future, no future, no future for you!’ Welsh’s more recent short story collections operate well within this fragmentary feel. In The Acid House (1994) we move from stories of lightning induced brain exchanges to Cambridge fellows ending up in car-park fist-fights over their philosophical positions.

Seamlessly shifting from philosophical observations to acts of crime, Welsh’s narrative clashes together different discourses in a technique called heteroglossia. Trainspotting’s ‘Courting Disaster’ episode is a key moment. Characters Renton and Spud have stolen books from Waterstones. Renton’s defence case? He was interested in Søren Kierkegaard’s existentialism and had stolen the books to analyse them philosophically. Renton — the addict and petty thief — follows with a hilariously eloquent deconstruction of Kierkegaard’s bourgeois, individualist philosophy. Here Welsh perfectly juxtaposes a high-brow philosophical critique against a narrative of low-born criminality. It is as hilarious as it is powerful in Welsh’s postmodern mastery of black comedy.

‘Choose a life. Choose a job. Choose a career. Choose a family. Choose a fucking big television. Choose washing machines, cars, compact disc players and electrical tin openers... Choose DIY and wondering who the fuck you are on a Sunday morning. Choose sitting on that couch watching mind-numbing, spirit crushing game shows, stuffing junk food into your mouth. Choose rotting away in the end of it all, pishing your last in a miserable home, nothing more than an embarrassment to the selfish, fucked up brats you spawned to replace yourself, choose your future.’

So goes the infamous soliloquy of Trainspotting with its repetitive viciousness, its biting cynicism, its curt confession on the hollowness of modern consumer culture, in the end, resembling nothing better than the heroin addiction it follows. Welsh’s repetition of ‘choose’ is, ironically, its own repudiation. Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting is, as The Sunday Times (somewhat patronisingly) reviews, ‘the voice of punk grown up, grown wiser and grown eloquent’. And Welsh is the founder and perpetrator of an unforgiving, self-consciously disruptive punk poetics. Hold the defibrillator — punk seems very much alive.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025