‘Both poison and antidote’: The Mays 31 review

Despite some gooier, more generic pieces, Anna Wythe finds the latest edition of The Mays to be rife with fascinating images and precisely crafted prose

When I think of literary critics, I think of the devil. More specifically, I think of Bulgakov’s Woland – a particularly sordid version of Satan. I can only aspire to his insouciance, his black silk dressing gown and talking cat. Woland is the scourge of Moscow’s literary elite.

Much like a critic, the devil is creation’s negative principle. He’s the angsty counterpoint to all the pretty things God made. Fortunately, Bulgakov’s Satan is also the champion of failed novelists and proletarian poets. If I can find that particular brand of provocation in this review of The Mays, perhaps I will escape being decapitated by a Moscow tram.

The miracle of a small book is its capacity for corners and crevices. I was drawn to places where The Mays perplexed me. Some images rush up you like a Labrador, but others have to be coaxed out into the open and even then remain taciturn. Georgina Hayward’s ‘Calf’ stopped my speed reading in its tracks. To understand the strange four-legged symbol at the heart of this short story, I had to think with the murkier parts of myself.

“The tangled histories of land and water are merged and submerged”

In a similar way, Miraya McCoy’s ‘Grandpa’s Hands’ and Coco Cattam’s ‘Clowning’ transform the flat page into tidepools. My eye explored these photographs like a swimmer testing water with a hesitant foot.

Poetry is another pathway to the swampier grounds of heart and brain. Patrick Romero McCafferty’s ‘Draining Lake Texcoco’ is one of the few linguistically daring poems in The Mays. The tangled histories of land and water are merged and submerged. Layers of meaning pile up like sediment. The sinking streets of Mexico City echo across an ancient lake.

Plot gives us another, equally pleasurable, kind of layering. There’s a particular joy to being in the palm of the author’s hand, eagerly awaiting their next move. Cian Morey’s ‘Flipping Coins’ is a tightly coiled spring of a story. The reader can never quite find their footing in the unfamiliar mind of the main character. Rupa Wood’s ‘Delight’ is likewise an expertly controlled piece, luring the reader in and delivering sudden shocks of adrenaline in a way its narrator would surely approve of.

At times, my tastes parted company with those of the editors. Much of The Mays is concerned with the intimate and nostalgic: first boyfriends, warm summers, gooey fruit, cosy bedrooms. Unfortunately, the preponderance of these pieces was not only cloying but it also had the effect of making such personal experiences seem painfully generic.

“I became increasingly frustrated with the lullaby language of the love poetry”

The sweet and tender curdles quickly. I became increasingly frustrated with the lullaby language of the love poetry. Is art really about scooping up the past and putting it in a snow globe? I wanted something riskier, more experimental.

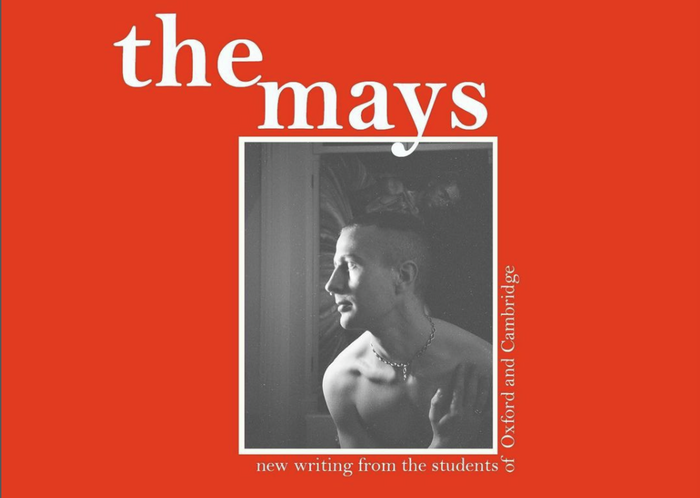

Perhaps the front cover should have warned me. On a peach-coloured background, a young child hesitates on a diving board. He has armbands and the water below is only a bath, yet he hesitates. Jump!

Obscurity has a bad reputation at the moment. It’s seen as the literary equivalent of emotional unavailability. Like baby penguins, we want everything raw and vomited directly into our throats. Chewing is a horrific proposition. I cannot help but prefer those pieces that latch onto something unfathomable, that risk being unintelligible in order to approach something hidden.

Some of my favourite pieces were those that managed to capture the intimate realm while simultaneously exploding it. Lily Isaacs’ ‘The Last Day of Rain’ initially seems like another narcissistic exploration of intimacy, yet Isaacs carefully interplays the power of emotion with the demands of community and survival. The narrator cannot bear the transformation of a willow tree, a symbol of her grief, into a communal work of art; it must remain a shrine to her private sorrow. ‘The Last Day of Rain’ reveals both the intense importance of love, and the dangers of unreflective wallowing.

Another short story, Maia Livne’s ‘On The Upperground’, brilliantly destroys the barriers that separate the intimate realm from the rest of the world. A perfect apartment is besieged by filth, both real and imagined. The sphere of intimacy is encased by privilege. The upperground requires an underground, and the heroine discovers that intimacy cannot survive unless it acknowledges that filthy other world.

The Mays is both poison and antidote. One moment I’m drowning in the strawberry milkshake of nostalgia, and the next my mind is being precisely diced by well-crafted prose. I threw it out of the window twice, but there are pieces I’m still re-reading.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025