‘Bodies like buildings’: life drawing in Cambridge

Madelaine Clark talks to student Zoe about her motivations, nerves, and realisations while being a life model.

There’s jazz playing. The old man in front of me takes off his towel, and starts dancing.

At least, it looks like dancing. Really, he’s deciding on his poses – a knee up – his hand goes on the wall – after that, he tries picking up a nearby stool. When he’s done, the man nods briskly to himself, quietly pleased with the choreography but keeping up a stoic air. It’s an odd kind of theatre – the bit before the show when the orchestra starts to tune itself. I find it funny in a cruel way, watching this man try to maintain normalcy in his birthday suit.

But when the first minute of drawing begins, it begins with the logic of a dream. In front of me, like a sleight of hand, the man becomes something non-human. This thing has no clothes on, I’m sure of it, but it’s not quite naked either. It’s made of flesh. It’s also a building, somehow.

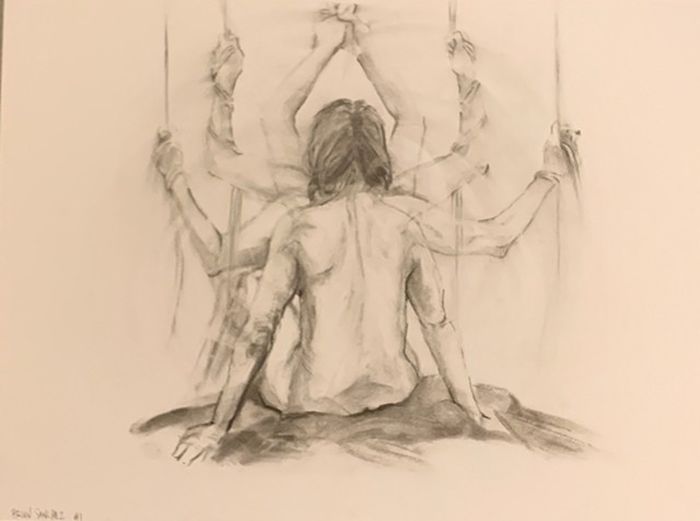

The five-minute pose begins: I trace the prisms of fat below his shoulder blade, and then each rib becomes a rectangle – six shallow flumes beneath just-sagging skin. The jaw and cheekbones look geometric. In his eye socket, I see a bay window, and in the curve of his stiffened arm, an archway. The room is still. Over the jazz, I hear drowsy pencils scuffing as the other students sketch. One girl smudges her shapes with black charcoal, pressing thumbs into paper and making it bruise; others are more diligent, opting for precision. I look up at the vault of the man’s back. The nodules of his spine curl and ladder upwards, like architraves on an old front door.

“This thing has no clothes on, I’m sure of it, but it’s not quite naked either.”

When I go to the ArcSoc sessions, I look at the models as if they were objects. But the experience doesn’t seem to carry any of the usual connotations of ‘objectification’. Sexiness never sparks. When we draw naked bodies, we break down the subject without any intention of dominating it, possessing it, or sexualising it. We look for shapes in skin.

In figure drawing, nudity is not something to shield or shy from. It rebels against clothed Victorian ideals. A Schiele painting I like – ‘Girl Nude with Folded Arms, 1910’ – portrays a feigned act of modesty, with the girl covering only her chest, leaving the rest bare – a comment on the arbitrariness of what we cover up. His work is queasy but often beautiful. Bodies fold and unfold themselves in gnarly sexuality; they’re shaped by a deformed kind of eroticism and they’re uncomfortable to look at. Schiele’s work, admittedly, was informed by his own paedophilic gaze, but its embrace of the aesthetic ‘obscene’ remains valuable. Despite her blood-glow, ‘Girl’ looks bored. It’s a quiet, mindless moment I see the models at Life Drawing get caught in. As I do every Friday, I find myself wondering what she’s thinking, if she’s thinking, why she’s there at all.

“Last year, at the end of the year, I got sexually assaulted by someone who I knew and still know. It’s not been discussed, and it kind of really fucked with me mentally.” Outside the cafe in Emmanuel, a few hours before the ArcSoc session this week begins, I sit with my friend Zoe, who modelled for them last term. I’ve asked her why she decided to sign up, given how awful the experience sounds on paper. “I’d always already struggled with body issues, but after [the assault] I felt like everyone was looking at me, always in a sexual way.” Zoe points out that the boy who assaulted her seemed “normal”, and so the feeling of being covertly sexually watched became a constant stress.

“Having been to life drawing a lot, I knew that it was a very non-sexual place. Going as someone who draws, you sit there, and you’re not thinking: ‘Ooh, yeah’.” She puts on a funny voice, imitating the ribald gruffness of a pervy American trucker. “You’re not there for any sort of gratification, so I knew that it was a very safe space.”

Was it not scary? “Beforehand I was very nervous,” she tells me. “Obviously you’re sitting there and you’re about to get naked in front of a room full of thirty strangers that you’ve never met. But I just had it in my head that I’m just shapes to them.”

“What they’re seeing –”, she pauses, thinking for a second. “They’re trying to figure out how to draw my shoulder and not how they can touch it.”

There’s an interesting tension in what Zoe has expressed. Being deconstructed – becoming a mere matrix of angles – somehow allowed her to feel more human. It marked a different kind of objectification, one which is not reductive, but which dismissed the body as a merely sexual token. I tell her a story from last year, when I saw a model I’d drawn on the corner of Silver Street and had the sudden realisation that she, too, had a body beneath her clothes.

“They’re trying to figure out how to draw my shoulder and not how they can touch it.”

“There’s such a disconnect between seeing people and then knowing that they’re people. I’ve seen some of them around, and they might still see me around – I don’t know who’s seen me naked.” She puts it bluntly when she reminds me that, cumulatively, “over 50 people saw me naked in one night.”

It’s a silly concept. When denaturalised, there’s something acutely ridiculous about paying five pounds each week to sketch a stranger’s posed, garbless, shivering body. But Zoe mentions how, by contrast, her friends and family find it taboo – “What do you mean you go – with the naked people?”, she ventriloquises with a scandalised flair.

The impoliteness of figure drawing is, in a way, its art. The sessions make perversity beautiful, and they highlight its importance in social dissent. To be truly perverse is to go against the grain. When we embrace taboo, we “stand critically outside one’s own society”, says literary critic Fiona Wilson, and “embrace a reflexivity that recognises that society itself is […] perverse.” Figure drawing balances artistic leisure with advocacy. It allowed Zoe to push against the violent event that altered her self-perception; it allowed an old man to become youthful as he danced around in a towel.

“The people who have seen me naked haven’t just seen me naked because they want something out of it. It was nice to go back to just being a body,” Zoe ends with. There are people still chattering in the cafe next to us, and I make a joke about this being a ‘Bare-All Interview’. When I leave her, she leaves me thinking about a quieter sort of rebellion – the kind that makes bodies tower like buildings – and that evening my pencil makes grooves with the jazz overhead.

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025

Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025 News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025

News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025