Botticelli in Cambridge

Loveday Cookson reviews the Fitzwilliam’s exciting new exhibition housing Botticelli’s ‘Venus and Mars’, speaking to the curators behind the relocation project

“The collection belongs to the nation”, announces the National Gallery’s website. Sparked by the purchase of 38 paintings by the British Government in 1824, the National Gallery has always been the collection of the masses. 200 years on, their new initiative, ‘National Treasures’, sees them lend 12 of the nation’s most iconic paintings to galleries across the UK. Monet’s ‘The Water Lily Pond’ finds residence among the cobbled streets of York, the other Venus in the programme, Velàzquez’s ‘The Rokeby Venus’, has a stint in Liverpool, while the Fitzwilliam in Cambridge is temporarily home to Botticelli’s Venus and Mars. The typical London-centrism is diffused in this project, sharing the spoils of artistic brilliance with those typically unable to access such a collection and offering a much-reduced commute, with the added interest of viewing these works in a different context of a mass celebration of artistic heritage.

“The typical London-centrism is diffused in this project”

I inquired into the decision making-process, finding an odd dissonance between placing Gentileschi’s self-portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria in Ikon, Birmingham’s contemporary art gallery. The Director of the National Gallery, Gabriele Finaldi, explained that all the galleries jumped at the chance to display the ‘National Treasures’, remaining elusive about the pairing process. It is not one I am dismayed at, as there is something extraordinary about the Botticelli. Having captured the imagination of viewers for generations, even having been previously overseen by the Fitzwilliam’s current director, Luke Syson, this Venus is arresting, complex, alluring, and entirely simple. The painting possesses a captivating portrayal of love and intrigue, inviting the viewer to delve into its enigmatic narrative and unravel the timeless secrets it holds.

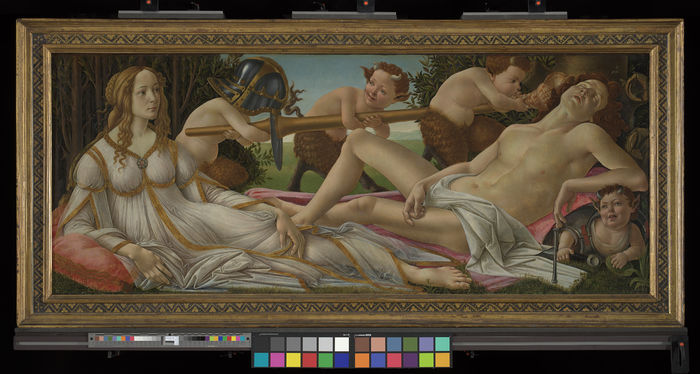

Mars languishes, his limbs sprawling in unconscious revelry, nude bar a single draped cloth, while Venus – in a departure from Renaissance convention – sits clothed in translucent white, her fixed gaze pulling the focus from the infantile games of the satyrs. But it is less the painting that is so captivating than the exhibition itself.

Swathes of fuchsia provide the backdrop. Above each display is a location – ‘in the bed chamber’, ‘in the study’, ‘at the dinner table’ – removing them momentarily from the narrowness of the gallery walls, reinstating their function and history and allowing us to dream as Mars does. Unlike its previous position at the National Gallery, viewers can get within inches of the painting, inspecting every brushstroke and interacting with it with the same intimacy as if it were hung in our bed chambers (or uni rooms).

“Viewers can get within inches of the painting, inspecting every brushstroke”

As attendees we are asked a single question: “what do you see?”. So simple, and yet it unlocks the painting, insisting we engage in the simple act of looking, compelled to forgo any need for artistic jargon and to return to the simplest of engagement. Discussing with Syson what he sees, he explains that “no matter how many times you come back to it, it changes”. He cites his recent noticing of faint sketches on Mars’ abdomen, clear attempts to refigure the proportioning until perfection and puzzle out the geography of how Venus is sat. “The painting didn’t really move” in its previous iterations, Syson says, but something about the dialogue it holds with the Fitzwilliam’s own ‘Venus and the Lute Player’ and the pops of pink it is pasted against brings a newfound dynamism to the once static work. Posing Boticelli alongside Titian invites visitors to engage in “looking out and looking in” as Syson describes. Botticelli’s Venus is fixed squarely on her lover, consumed entirely by admiration and their scandalous narrative, while Titian’s Venus throws her gaze outwards, entirely disengaged from her serenader: she is the single occupant of her narrative, crowned by cupid, but casting her attentions elsewhere.

The information panels offered are not there to feel “instructive”, Syson hopes: they aim to invite ways of looking, rather than telling you what to see. When asked about the experience of revisiting a painting he was so familiar with, Syson laughed. “It was just fun”, he told me, finding the process like “revisiting the past”. This embodies the aim of the exhibition, to revisit the past in the exploration of these Renaissance triumphs, but to have fun as we do, engaging with the painting on our own terms rather than the prescription of an information panel.

Finaldi aims to intercalate more of the gallery’s collection across the nation, hopefully making this one in a series of treasures we may experience from the comfort of Cambridge. While we may never have a Botticelli adorning our bed chambers, we do, for the first time, have one on our doorstep – and it’s your painting too, after all.

‘National Treasures: Boticelli in Cambridge’ is now open at the Fitzwilliam Museum until 10th September 2024.

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025

Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025 Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025 News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025

News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025 Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025