Slowing life down in Cambridge’s tiny streets

Looking for an essay distraction? Forget King’s Parade, and get lost in one of Cambridge’s many passageways, argues Niall Quinn

“Aww! Look at that tiny passageway, guys!” utters a wonderfully enthusiastic tourist. Frantically stumbling along King’s Parade on a blistering Saturday morning in early May, this phrase stops me in my tracks. Turning a blind eye to more pressing matters (the embarrassingly ancient pile of dirty clothes back in my room), my feet become sentient. They lug my laundry-panicked, supervision work-anxious mind into the cosy confines of St Edward’s Passage. This feels good, I think, as the adjacent Georgian bricks shelter me from the sun’s wrath — and my laundry.

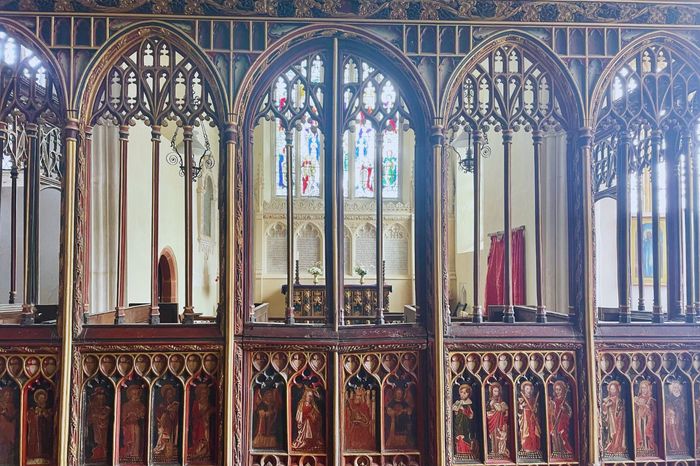

This has happened before. On many a brisk walk home, I have found myself loitering in one of Cambridge’s numerous tiny streets. Whether jumping to catch a glimpse of a graduation ceremony in Senate House Passage or admiring the neo-Gothic windows of All Saints Passage, spending time in passageways — passaging, if you will — has become a fundamental part of my Cantabrigian life. And I will even be so bold as to say that these crevices are a fundamental part of Cambridge’s being such a fine place in which to study.

“Cambridge’s passageways reflect the ‘cheek-by-jowl nature’ of the early town”

Why? Partly because they provide the antiquarian with a perfect field day. Cambridge has, of course, a surplus of architectural features that make one feel like a medieval monk. Towering gatehouses, itchy gowns, Latin dinner graces, vellum manuscripts aplenty in our old libraries — it’s a noble reward for all the hours spent memorising Othello quotes at A-level. But the passageways take this experience one step further. As the city council put it in 2016, in reference to fourteenth-century St Edward’s Passage, they “preserve a sense of the cheek-by-jowl nature of the early town”. In other words, the streets allow the passenger to soak up the atmosphere of Cambridge’s bustling, not merely its cloistered, medieval past.

Much like visiting the Shambles in York, it is difficult, when finding yourself in St Edward’s Passage, to resist becoming part of a tightly-packed stream of people on a market day. And because of the pedestrianised nature of the passage, you are free from the modern sources of distraction that usually yank you out of al fresco daydreaming. There is little chance (probably) of being hit by a tyrannical bicycle here. Gone are the Instagram notifications, the emails, the laundry baskets, and the Google Docs suggestions. All that remains is birdsong and teaspoons clinking, framed by a delightful mishmash of architectural styles.

“Narrow streets force us to examine the minutiae of life”

As his 1658 The Little Street attests, Dutch painter Vermeer was enamoured by this quality of petit streets. In that work, the street’s narrowness forces us to examine the minutiae of life. As the right-hand building collapses — almost with a sigh — into a modest, enticing alleyway, our minds undergo recalibration. Forget the world and its stressors, it instructs us: what exactly is that lady in white crafting? What is the other lady washing in that barrel?

A similar process occurs on Trinity Lane. The soaring, gargoyle-buttressed, nineteenth-century north range of Caius gently ushers the pedestrian toward the rugged bricks of Trinity’s medieval Nevil’s Gate. Now in a showdown with the two “CLOSED TO VISITORS” signs at the end of the street, a rewind is certainly in order. What on Earth are those patches of cheap red brick doing on a piece of Trinity? Are those gargoyles giving Trinity the metaphorical finger? Little streets, in short, make us better observers.

“Can tiny streets, then, be art?”

Here lies the most rewarding part of visiting small passages. Gently, if a little hypnotically, inducing us into a detail-finding bender, these spaces encourage us to discover and try new things. When I walk down St Edward’s Passage, for example, I find it testing not to wander into The Haunted Bookshop or St Edward King and Martyr Church, the “cradle of the [English] Reformation”. Replacing such distractions as egotistical BMW drivers with an abundance of enticing new spots, the tiny street leads one off course.

For many Cambridge students, myself included, it is difficult to truly let loose. Essay deadlines, supervisions, and laundry naturally take priority over mindless wandering. But spending some time, even for a few minutes, in the caring hands (or, should I say, walls) of the city’s tiny streets unleashes one’s subconscious curiosity — just the kind of faculty that will aid you in nailing that tricky proof, or working out what that Kant bloke was knocking on about. Can tiny streets, then, be art? If art is loosely defined as any human creation that conveys emotional or creative ideas, I would vehemently say yes.

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025

Arts / Modern Modernist Centenary: T. S. Eliot13 December 2025