In defence of the arts

Emily Cushion argues that we must foreground the Arts, even if those branches lead to uncertain ends

Upon coming to Cambridge in medieval England, students initially studied "a 'foundation course' in Arts – grammar, logic and rhetoric", before entering a particular field. The existence and popularity of that course demonstrates that the University regarded the understanding of the English language as its students’ priority, a prerequisite to all other types of learning. Arts were therefore the roots from which sprouted an entire ecosystem of learning in a multitude of subjects, vital to the growth of the university and its students. If Arts were deemed such a necessity in Cambridge’s early days, there is a certain discrepancy between past and present attitudes towards these subjects, which seems such a shame considering their continued cultural relevance.

"Arts were the roots from which sprouted an entire ecosystem of learning in a multitude of subjects"

For example, Vladimir Nabokov, who wrote the highly revered yet enticingly controversial novel Lolita, has sealed his status as one of university’s most successful literary alumni in the selling of 50 million copies worldwide. Some of Nabokov’s lesser known, yet equally poignant works draw on his experiences as a Cambridge student; he does this most directly in "The University Poem". Nabokov’s poetic preoccupation is obvious here, not only through his use of such a medium to articulate his time at university, but also in his mentioning of other poets, including fellow Cambridge alumni Lord Byron. Nabokov undermines his own meta-poetry: "But to think of poetry was harmful / in those years", suggesting that an affinity for the Arts, most specifically literature, was beginning to be frowned upon in his time. Nabokov implicates his disillusionment with Byron – "I have cooled toward his creations…" in a way that subscribes to the rising detachment from poetry, and arts in general.

Despite this attempt to replicate the current attitudes towards the Arts, Nabokov’s poem perpetually positions them as integral to his Cambridge experience, in also describing affiliations with music, philosophy, and architecture, albeit not in a strictly academic sense. There is a certain irony in Nabokov’s attempt to escape the Arts, being that it is communicated through them, and with such frequent attention that inevitably reveals their hold on him.

Underpinning all of this is the fact that, despite his subsequent career in literature, Nabokov himself was not initially a literature student at Cambridge; as Beci Carver writes in her chapter "Cambridge" in Vladmir Nabokov in Context, "Nabokov began his career at Trinity as a scientist" – more specifically a zoologist. At first, then, Nabokov firmly fit the category of a STEM student, before making a drastic "switch to Russian and French in his second year". He therefore demonstrates the potential for success in both STEM and Arts subjects – these are not necessarily distinct categories, nor sides to pick and stay with. Indeed, Nabokov poeticised his experience as a scientist in his poem "Biology", literally written in a Cambridge laboratory – such an amalgamation of Arts and Sciences defies the notion that these should be separate categories.

"I have witnessed a ridiculing of the subject I have chosen to devote not only the three years, but really an entire lifetime to"

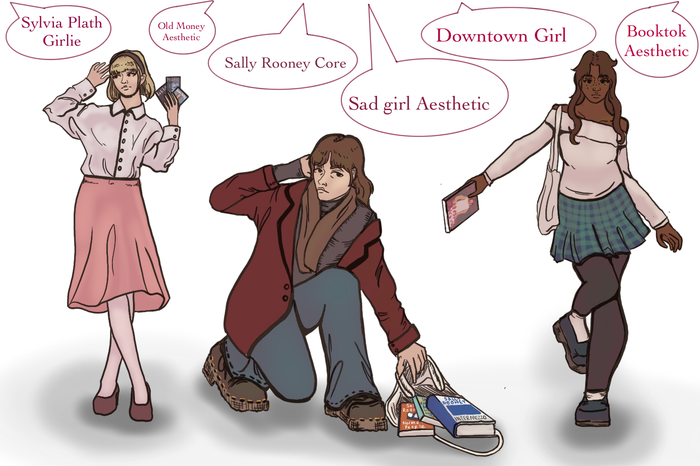

Across my time of studying English at Cambridge, I have certainly witnessed a ridiculing of the subject I have chosen to devote not only the three years, but really an entire lifetime to. English is consistently dismissed for being too easy, or less socially and culturally impactful than other subjects – an opinion that more than often comes from STEM students. Such an assertion seems laughable, considering the hold literature, and the Arts more widely, have on the world. They are inevitably entwined with everyone’s life, even STEM students, being the activities that we turn to most frequently to wind down after an intense working day. Watching a favourite film, making a Spotify playlist, choosing that one dog-eared novel yet again off a shelf that hosts a sea of academic texts – these are things we do on the daily, often without even thinking.

Literature is a medium used by every single Cambridge subject; it just so happens that in English, we write using the medium that we are discussing, making us doubly involved in this particular art. With its first examination having taken place little more than a hundred years ago, the English course at Cambridge is very much a new thing. While this might seem to reveal its uselessness as a subject, I would argue that the University has realised the necessity in permitting its students to study a subject so vital to everyday life. And despite, or perhaps even due to its disapproval, English seems to be needed now more than ever.

English, however, is not the only arts subject that is regularly dismissed – Philosophy, MML, Music, and many others all face the scrutinising sneer of a select few STEM students who, more than anything, simply view their work as more important. Such superiority ultimately stems (pun intended) from the notion that the sole and fundamental reason for a degree is to make money. I will not deny that English is less employable than many STEM subjects, or even other non-Arts based Humanities like Law, however my interactions with fellow English students in Cambridge have confirmed to me that nobody truly loves their subject as much as us. While I know other students, even STEM ones, must love what they do in order to be pursuing it at such a level, the rhetoric of internships and post-graduate careers permeating conversations has left me feeling disillusioned about the motivations behind studying at this university. The reality that comes with choosing a degree that doesn’t directly lead you into a high salaried career, even when that degree comes from Cambridge, cements the authenticity of this love for me.

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a letter to letters@varsity.co.uk or by using this form.

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge students are too opinionated 21 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025

Comment / Does the AI revolution render coursework obsolete?23 April 2025 News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025

News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025