Plein air painting and seeing with the eyes of love

Ryan Vowles speaks to Cambridge artist Sarah Allbrook about the unique beauty of plein air painting

Why are Monet’s paintings of his garden at Giverny so beautiful to us? Is it technical skill alone that makes Constable’s pictures of Suffolk so powerful? These artists often worked outdoors, depicting landscapes to which they felt connected. When we see a painting of a familiar place, or a familiar object, a great painter makes us think, “I had never noticed how beautiful that street, those hills, that bridge could be.” I believe the role of the artist is to remind us of beauty, not to create it, and that the quality of great landscape painting derives from the artist’s connection to and love for the subject. As William Blake said, the artist should “see Heaven in a wild flower” and should teach us to see in the same way.

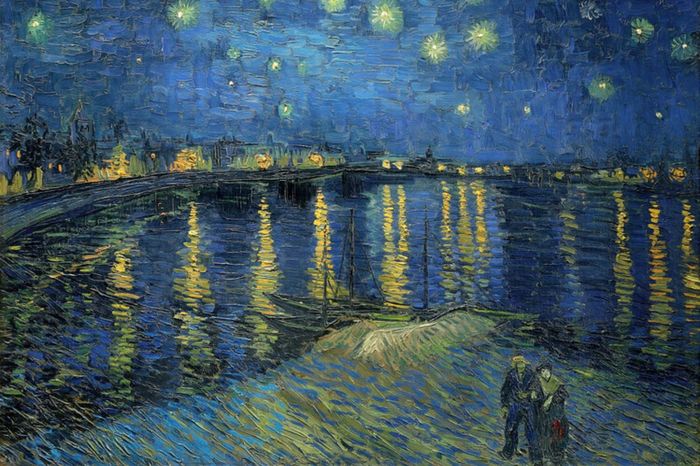

I recently had the pleasure of meeting the local artist Sarah Allbrook in her studio. Her paintings make immediate the beauty of this city, of the fens, the Cam, and the common greens. Allbrook works en plein air, which means to paint outdoors within the landscape. Pioneered by Constable, this method of landscape painting came to prominence with the invention of the sealed paint tube. For Allbrook, plein air is “trying to capture a fleeting moment, or a beautiful view… something that you think is worth recording.” Her work is produced quickly, in direct response to nature, as she told me “the light you want to paint, the exciting light, is very short-lived.” Just as Monet “desired to paint the air which surrounds the bridge, […] the beauty of the air in which these objects are located,” her approach is about atmosphere rather than form. This outdoor method, as was practised by Sargent and Van Gogh, is about immediacy, direct response, and intense observation.

“Just as Monet ‘desired to paint the air which surrounds the bridge, … the beauty of the air in which these objects are located’, her approach is about atmosphere rather than form”

Plein air is also about connection to place. Speaking of clichéd subjects such as King’s Chapel, Allbrook told me that she “didn’t go to the University, and so feels they’re a bit touristy, [she] doesn’t have a connection with those places so much. [Her] connection with Cambridge is as a city, and especially the rivers and the green spaces”. As art moved outdoors from the studio, so too did the subjects of Western art shift from the Greek myths and royal portraits to the fields, cottages, and streets of Europe. Beauty, which according to Kathleen Raine is “the real aspect of things when seen aright and with the eyes of love,” was found and portrayed in everyday places by those artists who inhabited and loved them.

Allbrook grew up in the countryside, and feels most connected to rural subjects. Trees and water give her “more freedom, whereas complicated architecture means you can’t be as loose.” Allbrook depicts the rural quality of Cambridge. For her, plein air is the most emotive form of landscape “because you’re responding to the weather and the day and the scene and the people passing. […] On a relaxing day your painting is going to reflect that, but then on a cold and freezing winter day you’re going to produce something different, maybe more rapid.”

“A quality of landscape, most famously exaggerated by Monet, is the uniqueness of each moment and the transience of light”

A quality of landscape, most famously exaggerated by Monet, is the uniqueness of each moment and the transience of light. In his words, “a landscape does not exist in its own right, since its appearance changes at every moment.” In his 25 repeated depictions of his neighbour’s hay-stacks, as in his 250 paintings of waterlilies, Monet described the relationship between that which is constant – the objects and the earth – and that which is dynamic; light, air, and weather. This idea is essential, that the artist depicts the moment and not the place. “For the scenes that I might choose to go back on,” says Allbrook, “it’s because I’ve seen that scene on a different day and I’ve seen the way the light is.”

Many of us will have cycled past Sarah Allbrook, or seen others out painting in the city. People often come up to her and comment “Did you do that just now?“, “You must be very cold”, and “That looks relaxing”, which she has learnt to enjoy. “It’s not relaxing at all really,” she told me. Instead, she paints for the satisfaction, and to appreciate nature. “You appreciate the place more deeply; you notice subtle things. If I’m with someone who isn’t an artist, they won’t notice all the things that I’m noticing, and I might point out the colour in the sky or the light through the leaves, something that they would just walk past. Quite often, when people see me out there they stop and remark at my painting. They look at the view differently, it makes them look at the view.”

As is the role of the artist, Allbrook reminds us of beauty; sunlight dappled on Jesus Green, Magdalene lawn reflected in the Cam, and the yellow of a winter sky at dusk over the town. She feels the purpose of her work is “to make people notice things and appreciate their surroundings.” Likewise, Monet’s connection to his garden, and Constable’s to Suffolk, charged their work with a profound love of place. By intense observation, by noticing the play of light and nuance of colour, we can begin to see the world as the artists do. Plein air painting, for me, is about learning to see the world “aright and with the eyes of love” and teaching others to do the same.

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a letter to letters@varsity.co.uk or by using this form.

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025

Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025 Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025 News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025

News / Cambridge professor paid over $1 million for FBI intel since 199125 April 2025 Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025