Why you should want to be ‘woke’ – and it’s not for personal gain

Responding to Gabriel Barton-Singer’s disavowal of ‘woke’, columnist Siyang Wei argues that mainstream caricatures of the term misunderstand structural problems

On Sunday, Gabriel Barton-Singer argued that the proliferation of the word ‘woke’ among the student left encourages a “conspiratorial” and “competitive” mindset, pushing us to look deeper and deeper for structural injustice where there is, in fact, no such injustice to be found.

“Sometimes,” he says, “we don’t have to think about the bigger picture or underlying structures”. If we took this on board, we could all presumably enjoy a nice, conflict-free life.

Counter to his assertion that ‘woke’ is a widely-used term in Cambridge, I am not sure I have ever heard someone use it without irony during my (fairly extensive) participation in left-wing student activism. His criticism of the groups on which he aims to comment appears not to come from any real experience or understanding of them, but instead from an exposure to the ‘political left’ that comes mainly from mainstream media outlets.

By placing problems such as structural racism in the psyche and morality of the individual, we lose the possibility for structural analysis

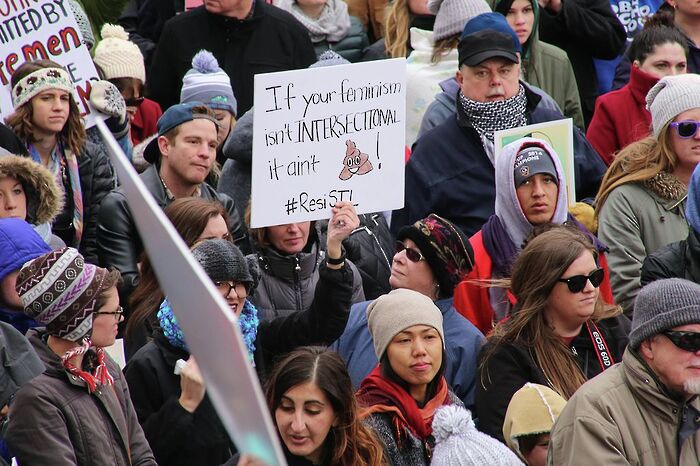

As several of those commenting point out, the history of the word ‘woke’ is long and far from straightforward. Despite Barton-Singer's attempt to frame it as emblematic of issues with Cambridge’s student left, the term in fact arose from a very different context – that of the black American struggle – and gained greater mainstream prominence with the Black Lives Matter movement, particularly among black Twitter users. Part of an urgent response to police brutality and mass incarceration, the maxim of ‘stay woke’ meant an awareness of systemic racism and violence, and a commitment to organising against it. Originally, ‘woke’ was less a term of political debate than a call to radical action for survival.

This, of course, is where social media and mainstream outlets come in. As Charles Pulliam-Moore writes, “it was only a matter of time before “woke” was co-opted by the mainstream (read: white) internet.” Since 2013, ‘woke’ has been transformed through its widespread misuse and memeification – by now, the original meaning has been all but lost, and the term is rarely used in earnest.

The relationship between activism and the mainstream manipulation of activist language is hugely ambivalent, as it simultaneously makes such activism more visible and limits its possible impact. Buzzfeed, Jezebel, Teen Vogue and others do not talk about cultural appropriation because they are the vanguard of the political left. They do so because it is easy, it generates hits, and it also generates a form of (white) social capital – and, in the end, it is profitable.

A criticism of ‘woke’ as it now appears might in fact discuss the way in which words that emerge from contexts of political struggle become devalued and appropriated, facilitated by the watchful monitoring of anti-racist and other radical communication online. Barton-Singer’s argument falls at the very first hurdle in presuming to make judgements about some essence of ‘wokeness’ without looking beyond its mainstream bastardisation. If we want to avoid a “social media ruckus” in search of something more productive, the solution is not to pretend that structures of racism and other modes of stratification may not exist after all.

That which we should focus on instead can be found in the example drawn upon by Barton-Singer. He refers to a white woman who posted photos from her prom on Twitter in which she was wearing a qipao; a Chinese user retweeted the photos, commenting: “My culture is NOT your goddamn prom dress.” The exchange subsequently received significant attention, with the tweets liked hundreds of thousands of times and erupting into a conversation about cultural appropriation. According to Barton-Singer, the “whole situation was decidedly unpleasant”, but “could have been avoided if we weren’t, as a society, searching for the evidence to support our woke theses and prove our political convictions”.

This incident, including Barton-Singer’s comment upon the competitive nature of the ensuing debate, is the perfect example of the result of the mainstream co-option of ‘woke’. We have entered into what is termed the ‘Woke Olympics’, where racism is presumed to “reside in persons and in objects rather than systems and institutions”, resulting in the misguided belief that locating racism within a person will enable us to eliminate it. By placing problems such as structural racism in the psyche and morality of the individual, we lose the possibility for structural analysis or collective organisation – that for which the term ‘woke’ meant initially to stand.

Like Barton-Singer, I am unsure about the utility of tweeting at one woman about her dress a thousand times – not because she and her qipao fall outside the bounds of racial interpellation, but because they are only one small and relatively inconsequential example of a far wider problem, with far more deadly effects. The real danger lies in a mainstream understanding that locates racism within her as an individual, thus obstructing a more radical, unsettling, but fundamental conversation.

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025

News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025 News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025

News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025 Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025

Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025 News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025

News / Varsity ChatGPT survey17 April 2025