The CUCA walkout is what political correctness should look like

Connor MacDonald explains why he walked out during James Delingpole’s address at this week’s CUCA Chairman’s dinner

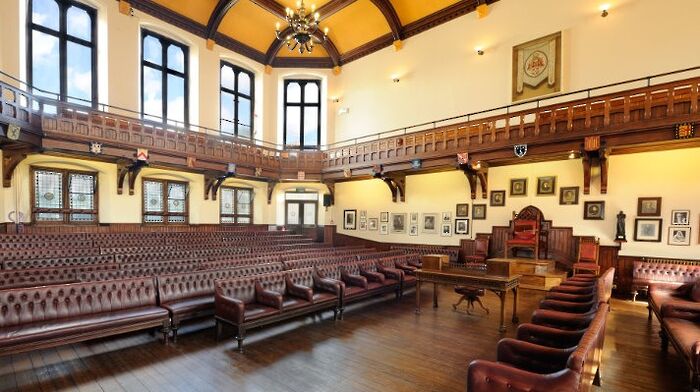

I was expecting James Delingpole to be rather bad, but certainly not that bad. Not 15 minutes into the speech, and he made some jokes about AIDS, compared himself (positively, I think) to Jimmy Savile and Rolf Harris, and had exclaimed in a voice that could only be described as genuine disgust that men did “not need to be lectured about how not to rape”. It was the kind of eyebrow raising performance one expects at a seedy late-night comedy club, not at a Cambridge University Conservative Association (CUCA) Dinner.

Then I walked out. About a third of the audience followed. Conservatives have long prided themselves on being the party of free speech, so why did we walk out? The answer strikes at the heart of the question of ‘political correctness’, and reveals an area where the left may have a point. The left is generally correct in claiming that no one should be compelled to listen to speech they detest.

For ‘political correctness’ to be intellectually robust, it has to demand a standard separate from the views themselves – a standard of conduct

When faced with speech that is clearly vulgar, there is absolutely no reason that one would be under any obligation to continue listening, not even under the auspices of ‘free inquiry’. It is the equivalent of saying that one must stay to watch a production of what you thought was The Crucible, only to discover its actually burlesque review, simply to preserve “artistic integrity”.

Similarly, the claims made by the small minority who stayed to listen fell back on the tired trope of “challenging” the speaker. If we were expected to constantly “challenge” those who make no attempt to offer a coherent argument, offering instead obvious displays of gratuitous vulgarity, life would be insufferable. This would only be exacerbated for those of a minority status, made to constantly defend their position in the face of those who, like Delingpole, say things such as “make a lot of money so you can send your kids to private school.”

However, my reasons for walking out were not straightforwardly political – and this is key. I did not walk out because he compared himself to a sexual predator, or because of his views on consent workshops, or because of his seeming unawareness on how AIDS is transmitted. I walked out because at no point did James Delingpole ever seem to grasp the seriousness of what he was talking about. There was not even an attempt to try to say anything insightful or meaningful – it was just a litany of inane babble.

It is here though that those, often on the left, who often argue about political correctness must be exceedingly careful. To dismiss someone as being politically incorrect, it is not enough to find their views stupid, or absurd, or harmful. For ‘political correctness’ to be intellectually robust, it has to demand a standard separate from the views themselves – a standard of conduct. Delingpole’s callous willingness to disregard one’s political opponent did not meet this standard of conduct.

That is why I felt the CUCA walkout had so much power. Given our commitment to freedom of speech, no reasonable speaker could have thought “they walked out because I’m too right-wing”.

When certain groups no platform indiscriminately (as in the case of the left with Jacob Rees-Mogg), ideological conformity abounds. What’s more, people like James Delingpole believe that they are simply being persecuted, rather than seeing the standards they are failing to meet. Surely this only stands as a further obstacle on the path towards healthy political dialogue.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025