EU youth mobility is exactly what the UK needs

The major parties’ rejection of more mobility for young people in the EU shows that the UK is not ready to deal with the effects of Brexit, even when it would benefit us most, argues Elsie McDowell

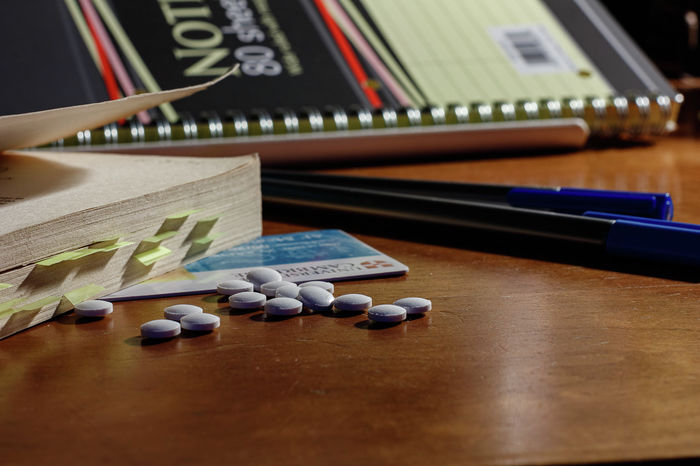

Midway through a procrastination-fuelled scrolling session, I got a notification with the headline: ’Brussels proposes return to pre-Brexit mobility for UK and EU young people’. I couldn’t believe it – as someone who had studied Spanish for years, working in Spain was something I had always dreamed of doing. Suddenly, it felt within my reach. After five minutes of excitedly texting my boyfriend about how much easier this was going to make his year abroad, it dawned on us: there was no way the UK was going to let this happen.

Unfortunately, we were right. This country remains one that is unable to deal with the self-inflicted harm of Brexit – and the UK government certainly isn’t ready for a conversation on anything as remotely sane as a youth mobility scheme with the EU. It took Labour and the Conservatives just a matter of days to shut down the plan. While I had grown to expect nothing more from the Tories, even as an increasingly disillusioned Labour voter, I held out a crumb of hope that Starmer would finally make a decision that felt like it was actually appealing to the student vote. Instead – with vague commitments to improving UK-EU relations in other ways – Starmer yet again failed to deliver for the young people of this country.

“I held out a crumb of hope that Starmer would finally make a decision that felt like it was actually appealing to the student vote”

Perhaps the most obvious impact of this scheme would have been cultural; aimed specifically at facilitating mobility for “students and trainees”, this scheme would have made it much easier for British students like me to train and study in the EU, and vice versa. My dreams of Spanish immersion aside, the European Commission stressed that “mobility would not be purpose-bound”, meaning that it could have helped tackle some of Britain’s worker-shortage-induced economic woes too. Looking beyond Sunak’s “stop the boats” soundbite, the UK is in dire need of immigration. As one of the only European countries whose workforce has not recovered post-COVID, in part because of Brexit, the UK would benefit from smoother mobility for young Europeans in order to fill some of the UK’s job shortages.

Above all, it would have been an important step in improving our post-Brexit relations with our continental neighbours. Instead, both of the UK’s major parties have fallen back on scapegoating the EU for problems they have caused – and failed to manage – themselves.

This appears to be just the latest instalment in the UK’s “one rule for us, another for them” mentality when it comes to the EU. Since the beginning of the European Economic Community, the predecessor of the EU, the UK has sought to have an especially advantageous position – all while not having to adhere to the criteria that other members in the bloc do, such as adopting the Euro.

So, just like when we were in the EU, the UK government is looking to “cherry pick” which bits of the EU it likes best by trying to pursue bilateral youth mobility schemes with individual EU states, like France.

Except now we can’t. In a way, the youth mobility scheme were a peace offering from the EU to a country that has continuously behaved like a spoiled child. Instead, true to form, our politicians have proved that they are not ready to provide an actual vision for what post-Brexit UK-EU relations should look like, by yet again shooting ourselves in the foot.

“In a way, the youth mobility scheme was a peace offering from the EU to a country that has continuously behaved like a spoiled child”

Brexit has damaged the UK immensely, sparking years of political and economic chaos. If the next Prime Minister of this country were sensible, they would accept a youth mobility scheme like this one. A full return to freedom of movement was never on the table – instead, it would simply mimic existing schemes the UK has with other countries, such as Canada and Australia, that still require background checks and proof of sufficient funds. It would be a relatively simple move that an incoming Prime Minister could make to show that they are willing to move on from the deep divisions that Brexit inflicted on the UK.

Economic and cultural benefits aside, in signalling that he would accept an EU youth mobility scheme, Starmer would be acting in his own electoral interests.

There is not much danger of many young people voting for the Conservatives; unlike political trends across much of the world, young British voters have essentially “abandoned” conservatism. However, this does not mean that they are turning to Labour: for Starmer, the danger is that they will not vote at all. Between 1964 and 2019, voter turnout amongst 18-24 year olds fell by more than twenty percentage points. Given Starmer’s recent u-turn on his climate policies, and his slow support for a ceasefire in Gaza, Starmer cannot take the youth vote for granted when his party is one that increasingly shuns the issues that concern young people.

Yet again, Starmer – in fear of the right-wing media – has shied away from a prudent policy. It is time for the UK to grapple with the effects of Brexit and make concrete plans for what it wants its relationship with the EU to look like in the near future. It does not look like Starmer is the man to do this.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025