Why I’m not a girlboss

Daisy Stewart Henderson argues that a culture of corporate feminism risks alienating women who do not fit the girlboss image

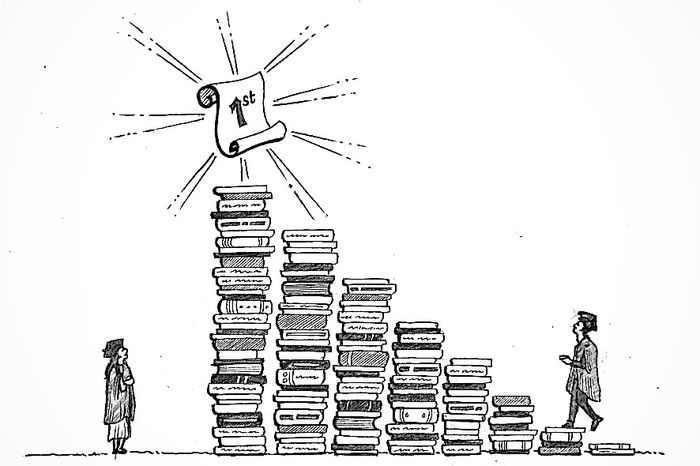

It’s easier than ever to be a girlboss these days. Internships offering young women the opportunity to enter the corporate world, or technology, or law, are widespread in 2025. Feminist societies and initiatives also often appear achievement-oriented. Don’t get me wrong: it’s great that you can go to a women’s only gym hour or running club, or aspire to be a woman in STEM or business. But a focus on self-improvement within feminism risks entrapment within the fallacies of the ‘girlboss’ trope, in which being an empowered woman becomes synonymous with careerist ambition and material success. It implies that to be sensitive, or content not being a leader or a pioneer, or to hold more traditionally ‘feminine’ aspirations such as being a mother or a wife, is incompatible with feminism. It endorses perpetually bettering ourselves to fit societal conceptions of success, rather than making peace with who we are.

“I wonder if the girlboss trope has more to answer for than we realise”

Preparing to study History at university, I noticed the encroachment of the girlboss trope into the biographies of historical women, where the label is teleologically applied to female historical figures at the cost of their complexity. Of course, strong and innovative historical women deserve our attention, but it always frustrated me that we don’t expect widely studied historical men to be ‘inspirational’ in the same way. Ultimately, Tsarina Alexandra of Russia was essentially the only female historical figure mentioned in my personal statement. Alexandra interested me, I think, because she was the antithesis of the girlboss. She managed to simultaneously embody pretty much every sexist trope I can think of: the hysterical mother, the Lady Macbeth wife, even the lewd adulterer, if you take Boney M’s word for it. Alexandra certainly wouldn’t qualify as a girlboss. But her reputation as a woman whose sheer hysteria brought down an empire has a great deal to teach us about how we view womanhood.

I recently went to a lecture about historical biographies, where Beatrice Webb was used as the case study. Webb was a pioneering social scientist dedicated to the eradication of poverty in Britain, who, along with her husband Sidney Webb, is best remembered for founding the LSE and the New Statesman. She also wrote three million words worth of diaries. In these, she discussed her political and intellectual interests, but also, at great length, her ill-fated affair with the liberal politician Joseph Chamberlain. Despite her outward appearance of girlboss empowerment, the countless emotionally-charged pages agonising over her enduring unrequited love for Chamberlain were, in Webb’s own words, “wanting in dignity and nicety of feeling.” Through her own writing, Webb emerges as both intelligent and deeply emotional, progressive yet assured of male superiority, a model partner, and also someone who described her husband as having a “tiny tadpole body”. These may not be the words of a girlboss, but, to my mind, they don’t undermine Webb’s status as a pioneering woman. They just make her human.

“It endorses perpetually bettering ourselves to fit societal conceptions of success, rather than making peace with who we are”

Perhaps I empathise with Webb because, according to the parameters the term sets, I’m not a girlboss either. On a superficial level, I suppose I could fit the bill. I’m at a prestigious male-dominated college, where I churn out essays on weighty topics, like Machiavelli and Stalinist ideology. I have spoken to important people with the appearance of confidence, and was even featured on a 30 Under 30 list of young women in Scotland, and dubbed “inspirational” on Twitter.

But the girlboss veneer does not do justice to the version of me that gets upset about Stalinism and children’s rights, and who is insecure in supervisions and while giving speeches. And that’s the valiant side of it. The real anti-girlboss within me has been known to become more hysterical over boys than I’d care to admit, and has spent more hours analysing Taylor Swift lyrics than the Discourses on Livy. Does this render me incompatible with empowerment?

I wonder if the girlboss trope has more to answer for than we realise. After all, could the characterisation of female strength as coldness be part of the reason why we are so reluctant to elect women? Could the alienation women like me feel from the demands of this trope be part of the reason why only 34% of British women identify as feminists? And if the benchmark of success is traditionally masculine stoicism and the ruthless pursuit of ambition, what hope is there for men to break free of toxic masculinity?

So no, I’m not a girlboss. Maybe it’s because I’m just too emotional for it, or maybe it’s because I want to be more than a masculine vision of success as determined by wealth and status. I want to be strong, but I am also fundamentally sensitive. But I don’t see why these need to be antithetical. Empowered womanhood should not come at the cost of our humanity.

Want to share your thoughts on this article? Send us a letter to letters@varsity.co.uk or by using this form.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025

News / Girton JCR publishes open letter expressing solidarity with Palestine25 December 2025