From Chanel to Yamamoto: When did black become black?

From the little black dress to Japanese art-design culture, Fashion Editor Isabel Sebode looks at the recent roots of the colour black and how it became a staple in our understanding of fashion

We understand the “new black” is an idiomatic phrase that represents a rise to popularity. Yet, the basis of this statement relies on our acceptance that for something to be the “new black”, black itself has to hold some kind of intrinsic value. Why?

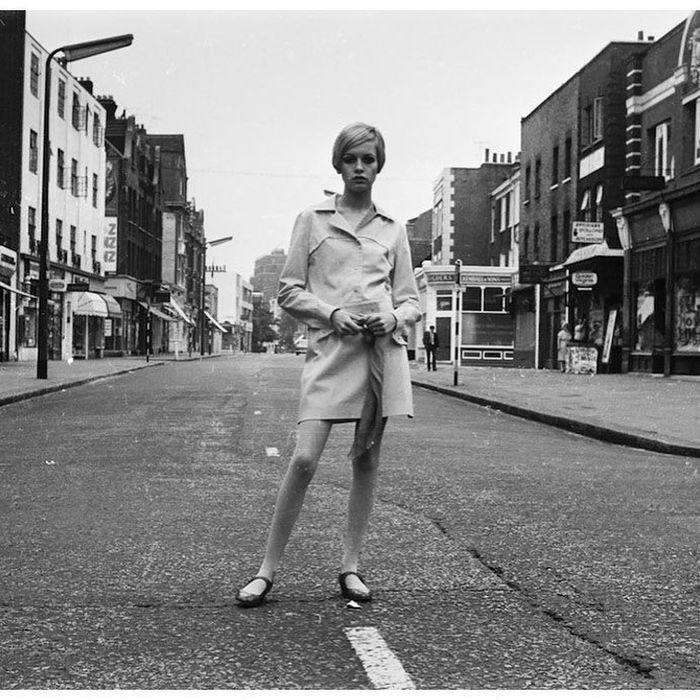

Whilst physics explains black as the absorption of all visible light, society has reinterpreted the colour not as what we don’t see, but as a sign of protest, grief, peculiarity, eroticism and chic, among other meanings. Rather than being a signifier of absence, black has become a classic in fashion, associated with various iconic looks and figures. Take for instance Holly Golightly, who stuns in "a slim cool black dress, black sandals, a pearl choker" wearing the dark glasses that dominate her slim face. Her character in Breakfast at Tiffany’s has become a symbol of what it means to be ‘chic’ or en vogue. The black accentuates her figure, without any colour or embellishments obstructing the smoothness of her silhouette. She is wearing the Little Black Dress.

“One is never over-dressed or underdressed with a Little Black Dress.” ― Karl Lagerfeld

In 1926, Vogue introduced the short black dress by Coco Chanel to the world as “a uniform for all women of taste”. A rather ambitious statement, which almost a century later turns out to be fulfilling its promises. Yet, Chanel’s creative decision is attached to a profound history of clothing, in which the colour and design was associated with the working-class girls, rather than the socialite elite that later popularised it.

In the 1890s, the black dress was the working attire of the ‘shopgirls’ – unmarried, young women working in dress and accessory shops and department stores. The simple black silhouette prevented the employees from being mistaken for the rich clientele, who wore more elaborate clothing. Thus the little black dress initially acted as a symbol of modesty, appropriate to the lower class, with the colour being even and inconspicuous in shade, as well as a distinction between the rich and poor.

Over the decades the black dress evolved, with Coco Chanel’s reinvention allowing the dress associated with the youthful shopgirls to be worn by more mature women. They adopted their style and reputation, particularly their youthfulness and femininity, that was a product of their age and interests. With the girls being unmarried, fashionable and self-sufficient, Coco Chanel saw in the black dress a potential for pauvreté de luxe or “luxurious poverty.”

“Some people think luxury is the opposite of poverty. It is not. It is the opposite of vulgarity” writes Chanel. Rather than defining luxury through distasteful pompousness, for the fashion pioneer luxury lies within the poverty of accessory and the wealth of taste and fashionable sensitivity. This is what the Little Black Dress embodies: a feeling of taste, a chic silhouette and an image of confidence in those who decide to wear it.

Black in fashion has naturally evolved from being limited to the chic little black dress. Skipping over decades of fashion history, we turn our awareness towards goth culture, which has merged the colour with intricate accessories as a defining feature. Simultaneously, the colour has become prominent in the scene of Japanese designers such as Yohji Yamamoto. Here black is the foundation to the artistic designs, who use texture, mass and form to explore the potential of the colour. Yamamoto in particular experiments with the shape of the clothing that is filled with darkness, and which drastically plays with the silhouette of the person wearing it; or as Tolstoy writes in Anna Karenina “the black dress with luxurious lace was not seen on her; it was just a frame, and only was she seen.” The visual allure of black clothing seems to be associated with its aesthetic integration: the entire composition is wrapped in the black mask, creating a sleek, coordinated and harmonious appearance.

Black is a colour that can provide modesty and provocation. Whilst a black turtleneck with jeans becomes a stylish gender-neutral look, a black silk dress is seductive both in the bedroom and at a party. Meanwhile, a black summer dress feels oddly depressing, whilst a black wedding dress is outright absurd. Hence, what is significant about black is precisely the fact that it is not just one style, one mood, one aesthetic or even just one colour. With an upper class reinterpreting the fashion of the lower class, one age group imitating another, we see that what is most significant about the colour is that it is natural for everyone.

I have only barely touched the surface of a deep history of the colour black in fashion. Yet, what quickly becomes apparent is that being the new black is not being ‘the next new thing’. Being the new black means being a new vessel for creativity, being a new form of artistic malleability, being the new unifying colour, which satisfies every aspect of what fashion is to us today and what it stood for in the past.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025