The Politics of Style

Fashion Editor Lara Zand unpicks our fascination with the way women in power dress

‘Politics is hell in general,’ Margaret Atwood tells Mary Beard in an interview for BBC Two’s Front Row Late, ‘but I think it’s probably double hell for women because not only do you have to have a position, you have to have a hairstyle.’

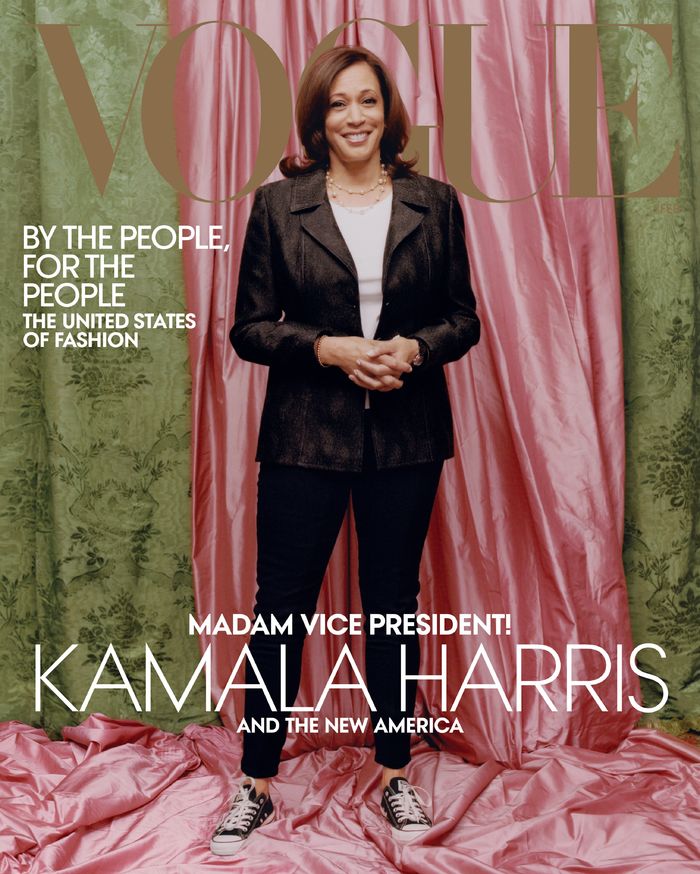

It’s not a stretch to say that fashion at the 2021 Inauguration attracted more fanfare than the average Met Gala. A grand-scale event involving high-profile individuals dressing up and coming together seems like a relic from a distant past, such that a handover of political power ended up catching not only the eyes of the public, but of fashion critics and connoisseurs far and wide. Spotlight on the wardrobe of Kamala Harris, in a majestic purple ensemble, continued, off the back of a campaign trail that saw her become a regular fixture in both Politics and Fashion sections: ‘Kamala Harris is the modern beauty icon the world needs,’ insists the Telegraph; ‘Kamala Harris Will Change Power Dressing Forever’, declares Vogue UK. She’s not the only one; last year Nancy Pelosi’s masks and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Telfar bag quickly became internet sensations. These three women were generally lauded for adding an unapologetic personal touch to their work wardrobes. But when fully registering the way in which these politicians’ clothes have become international topics of discussion, a Hillary Clinton tweet from 2019 comes to mind: ‘Bottom line: a good pantsuit is important. But never more important than what a woman has to say.’ So, as we attempt to look beyond the veneer of Girlboss celebration, perhaps we should be stopping to pose the age-old question: to what extent should female politicians’ dress sense be an object of focus at all?

That female politicians have always experienced a tricky relationship with fashion is undeniable. This dates back to the very moment that ‘female’ could be understood in the definition of ‘politician’. Official and unofficial dress-codes have existed (and continue to exist) since the day women were allowed to run for office. The early twentieth century welcomed the first female MP in Parliament and the first woman in Congress, yet wearing trousers was not acceptable until as late as the 1990s. Attire should be dark and demure: not too feminine, nor too conservative. There was no sense then that 100 years later, a record number of women would be sworn into Congress, among them women wearing a traditional Pueblo dress, a thobe and a hijab.

“Dress nicely but not too nicely; wear makeup but not too much; be feminine but not too feminine.”

But congratulating ourselves on the pace of change would be premature; we don’t have to look further than the press treatment of a politician like Hillary Clinton over the course of her career to see that. Though Marie Claire may now hail her as ‘the undisputed fashion icon of our generation’, the self-proclaimed ‘pantsuit aficionado’ was ridiculed for decades for her bold colour choices and experimental silhouettes. In one piece (on the then presidential candidate), Daily Mail called a classically feminine dress ‘frumpy’, yet a more androgynous waistcoat with cargo pants was ‘out of place’, and a loose cardigan ‘aged her and hid her figure’. If you’re wondering exactly what they wanted from her, you’re not alone. Even the adoption of her inoffensive signature pantsuit would not pacify critics. ‘Why must she dress that way?’ moaned Project Runway’s Tim Gunn in 2011: ‘I think she’s confused about her gender. All these big, baggy menswear pantsuits? No, I’m really serious.’

“Does a lack of appropriate vocabulary to speak about women in power suggest a discomfort with that very concept?”

Vanessa Friedman of the New York Times has famously defended the decision to cover politicians’ fashion, citing, for one, the many male politicians whose attire has also received attention. It’s true that it’s an increasingly common, though not nearly equal in measure, phenomenon; the layers of meaning behind Joe Biden’s Ralph Lauren suit at his inauguration, for example, were carefully dissected. It’s also worth noting that there’s coverage of politicians’ dress and there’s coverage of politicians’ dress. There’s a New York Times analysis on the significance of Kamala Harris’ white suit as a symbol of women’s suffrage, and there’s the Daily Mail’s infamous ‘Never mind Brexit, who won Legs-it!’ front page featuring Theresa May and Nicola Sturgeon.

The scrutiny in the press can only be a reflection of scrutiny in the real-life work environment. Dress nicely but not too nicely; wear makeup but not too much; be feminine but not too feminine. A handful of moments that made headlines give us a telling insight into the day-to-day: former French minister Cecile Duflot being noisily catcalled in the French Parliament in 2012 (in a dress that later took on a life of its own as somewhat of a women’s resistance symbol); the vitriol directed at Labour MP Tracy Brabin last year after her dress slipped off her shoulder in the House of Commons. ‘I get constant comments on the clothes I wear,’ Labour MP Jess Phillips told Vogue UK in 2019. ‘People will send you policy emails, being like, “I actually think it’s quite reasonable what you said about Brexit, but we couldn’t concentrate because you could see a bit of your cleavage.”’

What does this fixation say about us? That we still can’t take women seriously? That the only way we know how to talk about them is image-based? That we can still only exclusively associate them with the front pages of fashion and beauty magazines and not political columns? Does a lack of appropriate vocabulary to speak about women in power suggest a discomfort with that very concept?

And so, whether she actively opts to express herself through fashion or not, a woman’s dress choices will be subjected to scrutiny. But this surely tells us something we’ve always known about clothing: that it holds immense power. That it can send an unspoken message. That it can act as one more tool at the disposal of women in power. And recent years have seen an increasing number of women consciously harness this tool.

Politicians have time and again donned white, for example, to pay tribute to the women’s suffrage movement – from Shirley Chisholm to Geraldine Ferarro to Kamala Harris. Democratic Congresswomen wore all-black to the State of the Union in 2018 in solidarity with the #MeToo movement, whilst last year Michelle Obama let her viral ‘Vote’ necklace speak as loudly as the contents of her Democratic National Convention speech. There’s no doubt that fashion is made an object of political fascination. But a generation of women in power are using it to their advantage, taking back control of something that was for so long used as a weapon to distance them from the very idea of their profession. Ocasio-Cortez encapsulates this outlook in her response to criticism she faced for appearing in a loaned designer dress: ‘Sequins are a great accessory to universal healthcare, don’t you agree?’

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025