School girl obsession

The fashion industry has a dark fetish for young girls. Fashion editor, Eva Morris, investigates just how far this obsession goes

There are some conversations which run clear in my mind long after I’ve had them. Not because of anything particularly said or revealed, nor do I particularly remember each specific word said, I just have a clear image of it. One of these conversations was with a friend last summer. I can’t remember exactly what I wore, but I do remember stack socks and tan loafers. I say this because the conversation was about fashion’s unhealthy obsession with young, prepubescent girls and had started with a comment on how a lot of models are spotted at the very young ages of 13 or 14.

Stack socks, or loose socks as they are sometimes called, are a Japanese trend worn by high school girls as part of kogal culture. Kogal culture evolved in the mid 90s and involves wearing outfits in the style of Japanese school uniforms with alterations such as very short skirts. The girls who took part were named ‘kogals’ or ‘gyaru’ (Japanese slang for the English ‘gal’), even having their own text language. At the time, this trend received a lot of attention from the media which both sexualised and shamed kogals, with articles showing how to dress like one while also casting them off as vulgar.

“Only when the male gaze was added to the equation did the original signs of rebellion start to reek of fetish and objectification”

Miller (2004) described kogals in an article for the Journal of Linguistic Anthropology: ‘instead of restraint, there is self-assertion; in place of modesty, there is self-confidence’. So, perhaps this trend is instead something to be admired, a subversion of docile femininity and a reclamation of sexuality. Yet there is an obvious dark side of focusing on the sexuality of young girls as it can easily turn into claiming their sexuality. In modern day Japan, the trend has turned into nothing short of fetish (for example: the Guardian article, ‘Schoolgirls for sale’). It didn’t start this way with the kogals. They started off as an empowering symbol. Only when the male gaze was added to the equation did the original signs of rebellion start to reek of fetish and objectification. But this fascination with school girls is not limited to Japan.

Fashion isn’t easy to contain. The obsession with young girls elsewhere is more subtle maybe, but no less prominent. Just look to the 2010’s — everyone remembers all the pinafore dresses and tunic dresses so frequently worn by influencers like Zoella. Both of these items were staples of a typical Victorian school uniform. But this is not fetish, you might say, there’s nothing sexual about Zoella. Let’s take a look at a different example: Hedi Slimane’s Yves Saint Laurent, a fashion house associated with extremely thin models. Models with no boobs, and very little fat elsewhere.

“She can be vulnerable, feisty, vulgar, inaccessible and distracting. But never is a school girl the leader”

This kind of look is near impossible for most women to achieve, yet such small frames are common on prepubescent girls. Before puberty hits, girls are often skinnier, lacking boobs and curves, while after puberty most girls develop more of a figure and gain more fat all over the body. The kind of body type seen on younger girls, whether explicitly in uniform or not, was being perpetuated by both Western and Eastern media. If you’re not convinced this is a close enough connection, consider Kate Moss’s first photoshoot with Vogue. In spring 1993, Kate was 19 and the shoot took place in her old school in Croydon. She’s photographed in all white with a strap falling down her arm, clutching her arms around her. The very picture of schoolgirl innocence.

It’s hardly a surprise to see that fashion still projects these ideals. Although the Western fashion industry has changed and continues to change, including different body types and ethnicities and involving other genders and masculinity more often, a lot of the first Western designers purely targeted rich, white women. Rich, white women were the ones buying dresses for their debutante and to attract the attention of suitors. In the Victorian era, young girls were able to marry from the age of 12, but tended not to until 18, and so there has always been a short timer on the desirability of women.

There are obvious dangers when combining sexuality and school girls, but one thing I don’t think is talked about enough in this context is what it represents a school girl to be. According to these tropes perpetuated by the school girl image in fashion, she can be vulnerable, feisty, vulgar, inaccessible and distracting. But never is a school girl the leader. Even when seen in a more positive, harmless depiction — take Hermione Granger in Harry Potter — she is known for her smarts but always answers to the male hero. Whenever a decision is made or action taken, Harry says when, where and how. The school girl is forever the side character.

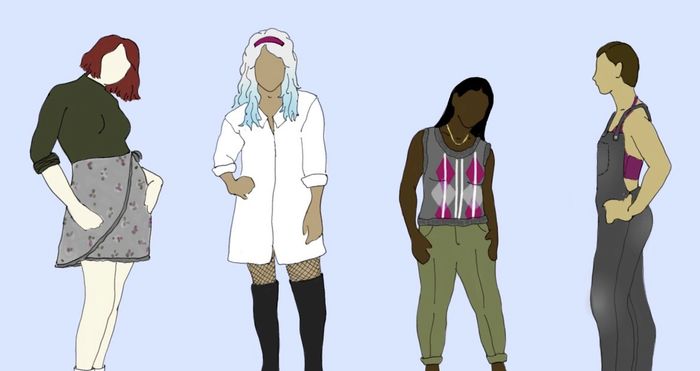

Even in Cambridge, I see these styles again and again: long socks, short pleated skirts, bows in long hair. There is nothing inherently wrong with these styles and we can’t escape them. For some, they can even be freeing — like for the kogals. But, when wearing my stack socks again, I will make sure to be just a little more loud, a little less modest and certainly won’t take any spot as a side character.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025