‘Grief is something felt more acutely in the face of trials’

The person you lost would want you to face trials and tribulations head on, writes columnist Ana Ovey

It’s not a revolutionary statement to say that Cambridge is a high pressure environment. Nor is it one to say that all of us, as students here, may approach failure with a less forgiving mind-set than we ought to. But as with all things, grief exacerbates the feelings that anticipate and follow failure.

Bereavement, paired with not just a university working environment, but the Cambridge one at that, makes for greater despondency in the face of adversity. It’s easier to feel burned out, more exhausting to carry on in spite of dud essays and awkward classes. Multiplied with anxiety or depression, failures, setbacks, or missing the mark or deadline, are painful and overwhelming. Concentration is knocked, anxieties build with the loss of the unconditional support and encouragement a parent often provides, comparisons of personal failings with the successes of others are crushingly constant. It’s infinitely more difficult to feel proud of your achievements when the person who would feel proud of you isn’t there to express it.

“My dad was always at the side-lines, commentating, beaming, cheering me on”

And, naturally, grief is something felt more acutely in the face of trials. I will still feel a particular kind of sadness at the thought of my father when surrounded by my friends, playing music and dancing, joking and laughing. But despondency numbs me and removes me when I’ve had a bad day, when I’m lonely, when I haven’t achieved what I wanted to – and I can’t call my dad and talk to him about it. Being bereaved at university is not something I anticipated in the years of envisioning my education after school. And even if it had been, I hardly know how I would have foreseen the acuteness and strangeness of every sorrow. As it was, it was a constant comfort to know that, even at university, if I were ever confused about what I was learning or upset about how things were going, I would be able to contact my fiercely intelligent and always consoling father about anything, never being made to think them insignificant. To have that removed, to be unable to articulate why I felt entitled to the presence of my dad, even in the background of my university experience, makes the weeks when I’m struggling with deadlines, mental blocks or worries even more difficult.

“Graduation will be hard without my dad”

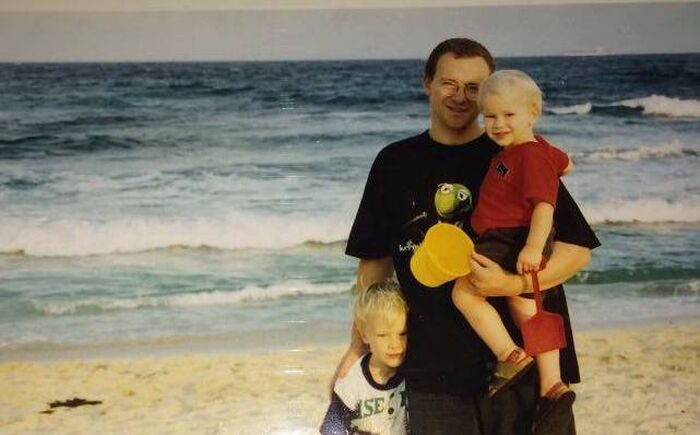

Talking to another girl whose dad had died, I was struck, in the sweetest and saddest of ways, by two things she mentioned while we were speaking of grief, particularly regarding our careers in Cambridge. The first was that, profoundly, ‘I feel as though I’ve lost one of my biggest cheerleaders!’ – which rang especially true. My dad was always at the side-lines, commentating, beaming, cheering me on and applauding louder than any other, after all of my victories – whether they were personal, academic, or extra-curricular. He made sure to love what I loved, and care passionately for whatever I attempted. He was also there, comforting me, booing the opposition, setting out practical comeback strategies in spite of obstacles, and shouting at the referee, after any of my failures. He never made me feel inadequate, despite his investment in my goals and successes. It’s a difficult thing to be deprived of that; it’s difficult to cope with it in a place as rigorous, intensive, and often unforgiving as Cambridge. Losing your head cheerleader, it turns out, is a big thing.

The other thing the friend mentioned, when we were discussing the academic and emotional impacts of grief, was her heartache at the notion that her dad would not be present for her graduation. It’s a particularly hard thought for children whose joy it was to make their parents proud. I remember my dad’s delight at my GCSE results, at my flute exams, at my writing, at my A levels, at my university offers.

I also remember the day I got my Cambridge offer and how inconsequential and foolish it felt. I got the email confirming I had a place the day I landed back in England from Sydney, after my dad’s death. What I had fretted over, what I had wrung my hands over, what I had hoped for after first being told I ought to try for Oxbridge, was suddenly utterly insignificant. In the moment I read I had an offer I realised I would always feel this way. Without my dad to hug me a warm congratulations, to laugh and exclaim, ‘Of course you got an offer!’, to say how proud of me he was – what did it matter? What was the significance of this small victory, when I was so overwhelmed with sadness?

Graduation will be hard without my dad – as will every failure and disappointment from now until then. But it’s a joy to reflect on all the kindnesses and encouragements he imparted to me, how much he would have loved to hear of all that I am learning, how he’d complain and roll his eyes and tut at anyone who made me feel as though I didn’t deserve to be here. It’s easy to forget these things. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed, it’s easy to feel hopeless and desire nothing more than to give up for the week, the month, the term. But, griefsters, it’s a bittersweet kind of bliss to remember how, more than anything, the person you grieve for would want you to be kind to yourself, would want you to succeed because it would make you happy, and vitally, would see your worth in spite of your failures. Endeavour to see it for yourself

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025 Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025 Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025

Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025