Let’s talk about Polycystic Ovary Syndrome

Maya Yousif sheds light on a hormonal condition affecting women around the world

Content Note: This article contains detailed discussion of body image and mental health.

Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) is a common hormonal condition said to affect 1 in 10 women across the UK. It is incurable, and often (but not necessarily) diagnosed around puberty. Whilst living with PCOS can be challenging, it is ultimately far more manageable than its rather frightening name would initially suggest.

When I was diagnosed aged eighteen, I was devastated. I’d never even heard of this condition before, so, naturally, I began to fear for the worst. I was both reassured and confused upon being told of its notably high prevalence among young women: if it is indeed so common, then why is it not taught in schools? And why aren’t more people aware of it?

This is in part due to a failure of our education system in its impractical (and often absent) teachings on sex, health, and wellbeing. PCOS is caused by elevated androgens (male hormones) in women, and this can cause higher levels of facial and body hair, irregular periods, non-existent periods, fatigue, ovarian cysts, weight gain, acne, sleep apnoea, irritability, depression, mood swings, and infertility. Not everyone experiences all symptoms, and many experience them to varying degrees.

“Young women are taught that there is a normative, monolithic experience of female health.”

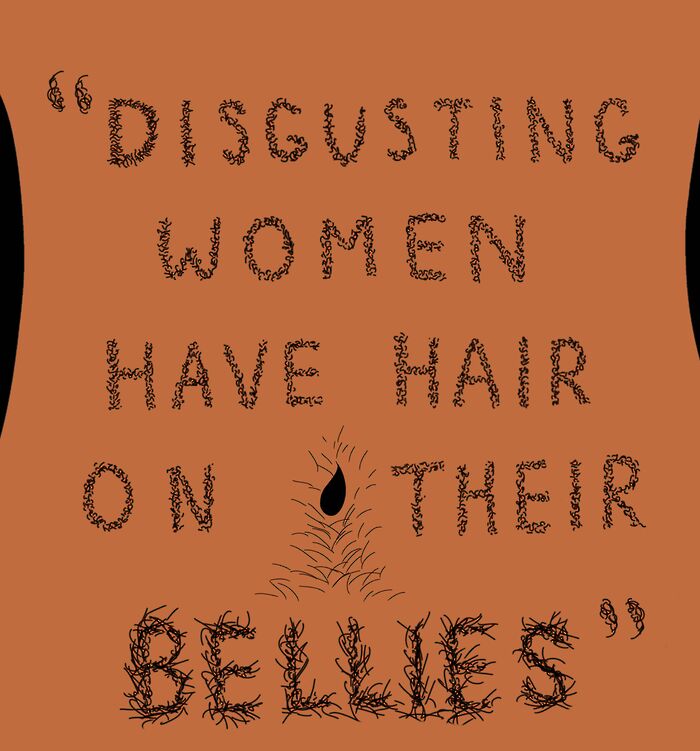

The manifestation of these symptoms in pubescent women without sufficient education can cause feelings of shame and social embarrassment. As we are all well aware, mainstream culture has popularised a standard of female beauty that is already unattainable by women. Our incessant exposure to images of slim, clear-skinned women with little to no body hair has popularised an ideal that is both deeply desirable, and fundamentally impossible. The pressure for teenagers and young women to conform to such an ideal is heightened for those exhibiting symptoms of PCOS, and girls without a diagnosis can look to their own developing bodies with an elevated sense of self-consciousness, frustration, and anxiety. This can feel alienating: you are in a perpetual battle with puberty, and always feel that your body is not quite right.

A lack of discussion and awareness around hormonal conditions combined with this pressure to conform to a particular aesthetic means that many feel embarrassed about their symptoms and turn to dangerous practices. One study in particular has shown that the number of women with eating disorders and PCOS was over four times the rate of eating disorders among women without PCOS. Statistics like this are emphatic in their demonstration that there is a significant gap in the way that schools teach issues of sex, puberty, and well-being.

Young women are taught that there is a normative, monolithic experience of female health. At around age 11 we’re told that one day we’ll menstruate once a month. In following years, we are taught about STIs, and then we learn how to put a condom on a plastic phallus. That tends to be the extent of it. So, when we don’t discuss irregular menstruation, mental health, or the variegated experiences of puberty with young women, the statistics concerning disordered eating and PCOS unfortunately make sense.

When we learn about hormones, it’s often hard to remember that they are not simply answers to GCSE biology questions, but real things that form a vital part of our physiologies and impact on both our mental and physical health. Women with PCOS are 40% more likely to experience anxiety and/or depression, but are not taught the multitude of ways in which this can be managed. Many turn to the pill, which is an oft-espoused treatment of PCOS due to its regulation of periods. However, many girls report mood swings, irritability, anxiety, and depression. There is not one solution for all.

While the pill may work for some women, many studies show the overwhelmingly positive impact of regular exercise and a balanced diet on managing symptoms of PCOS. On the arduous path to understanding my body and my condition, I’ve had to learn these things through trial and much, much error.

I am optimistic for a future in which sex education will make room for such discussions, meaning that teenage girls who struggle with PCOS or similar hormonal conditions will feel less alone in their struggles. For now, let’s keep the conversation going.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026

News / New movement ‘Cambridge is Chopped’ launched to fight against hate crime7 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025