Translating the untranslatable

Cecily Fasham writes about the trickiness of translation, how it relates to religion, and how she keeps falling in love with the untranslatable

There’s a certain glamour about untranslatability. Words like hygge, zeitgeist or flâneur (to name a few) have become buzzwords denoting particular aesthetics. They are apparently ‘untranslatable’, expressing concepts so peculiar to their own culture that there is no equivalent in other languages, and so they have come into English untranslated (though probably horribly mispronounced).

The fascination is that these words give names to concepts that are somehow simultaneously alien or indescribable, and intensely familiar – who hasn’t experienced schadenfreude (German: pleasure deriving from other people’s misfortune) or seen komorebi (木漏れ日 – which, according to the internet, is the Japanese word for sunlight filtering through trees)? Often, untranslatable words also offer ideas which are beautiful or thoughtful: my personal favourite is the Swedish smultronställe, a ‘wild-strawberry place’, which is a special, secret place that you must only visit with someone you really love (according to the Eva Ibbotson Young Adult romance novel, Magic Flutes, which I obsessed over as a teenager, at least). Untranslatable words give us ways of naming things that we might never otherwise have been able to quite put our finger on or adequately describe.

“Moments like this are why we love our languages.”

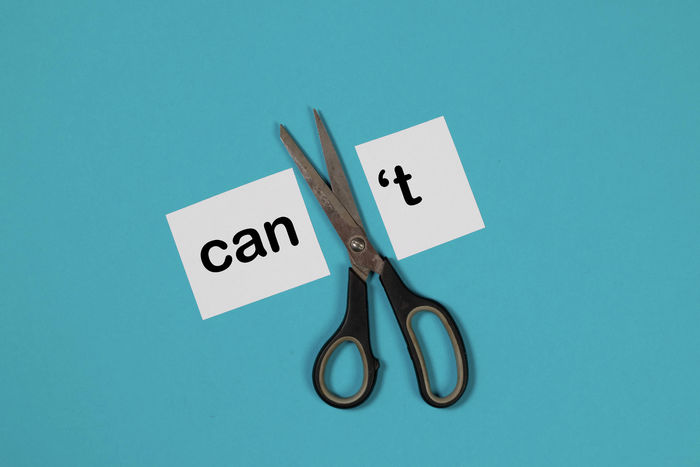

Untranslatable words are a paradox in that sense. On the one hand, they seem to show us how much we all experience the same things; we meet these words in other languages and think, ’oh, there’s a word for this thing that I feel – it’s not just me’. But, at the same time, they demonstrate the rifts between people caused by languages, the gaps between my English-language comprehension of the world and the understanding of someone who speaks a different language. Untranslatable words are moments when the impossibility of perfect, fluid translation crystallises: you cannot convey all the meaning.

In spite of its impossibility, I still see translation as a necessity. For me, as a Christian, this is theologically rooted: language barriers are a result of a fallen world; languages are designed to separate us – to curb our arrogance in thinking we could set ourselves up against God, as we did when we built the tower of Babel (Genesis 11) and God introduced languages as a source of confusion amongst humanity.

But my God is also a God of translation. The first act of the Holy Spirit at Pentecost was an act of translation: the disciples came out into the streets and proclaimed the good news of Jesus, and everyone heard them speak in their own language. As a protestant, Biblical translation – the ability to encounter the Word of God in my own language – is fundamental to my faith. People died during the Reformation so that I can hear God speak my own language. Translation projects remain a form of missionary work: my church, Holy Trinity Cambridge, supports a member of the church who works in Tanzania to translate the Bible into local languages, so people there can meet God in their own language. I have to believe that through God – through the work of the Holy Spirit – trustworthy translation is possible. After all, as Jesus himself said (though referring to salvation rather than translation): ‘with man this is impossible, but with God all things are possible.’

“Untranslatable words are what make you fall inescapably in love with a language, and what keep you pursuing it.”

On a secular level, being able to share astonishing concepts only found in other languages with monoglot readers who would never otherwise encounter them is the dream. Difficult as it is, it’s what we do translation for.

Kate Briggs writes eloquently in This Little Art, her book on translation, about the frustration and fascination of untranslatable moments. One thread of the book is about the correspondence between the 20th century French novelist, André Gide, and his English translator, Dorothy Bussy. In the letters, it’s clear that Bussy is in love with Gide. Her direct-indirect expression of this is to write, ’Je vous aime, cela sonne mieux en français.’ Briggs writes, ’I love you, it sounds better in French (would be the obvious – the only? – translation). But the vous. It is striking and important: what it is to make a declaration of love with a formal ‘you’.’

It might take a whole book to express what here is expressed in such ‘small compaction of language’, she explains: ‘I could write something for you on this moment, of this moment, but I’m not sure I’d call it a translation.’ It’s a moment that stops the translator in her tracks, but it’s also part of why this exchange is so interesting, so electric. Moments like this are why we love our languages.

For me, the word is ’trover’. It’s a word from medieval Insular French (the French spoken in Britain after the Norman conquest). According to the Anglo-Norman dictionary, it means ‘to compose’ or ‘to invent’ (usually in writing), but it also means to find, seek, meet with, come across, and is the origin of the Modern French ’trouver’, to find. As I keep telling everyone, it’s almost as if everything were already written, somewhere, somehow, and writing is somehow just finding some part of a thing that already exists.

I met this word, trover, while working on a set-text for translation in the Post-Conquest paper of the English tripos. For the exam, I’d have had to translate it as ‘find’ or ‘write’, depending on context. But to do that felt like such a loss; I’ve been obsessing over it for so long that it’s become a pinpoint of my thinking. I’m planning to do a third year dissertation on the play I met it in, in large part because of it.

My fascination with impossible, untranslatable words like this is what has kept me studying Insular French, despite it being an objectively hideous language. Think French, but someone’s put it through a washing machine and tumble dryer on the wrong settings; it’s peppered with k’s and z’s, all the syllables are pronounced, and you can speak it in whatever accent you like.

These things are like that. Untranslatable words are what make you fall inescapably in love with a language, and what keep you pursuing it. They’re total nightmares for translators, but trying to translate them reveals the shadow-work at play in particular words. They show us what learning other languages is about, why we keep doing it, trying to translate, because you can’t get the same intricacy of understanding if you never reach beyond the limits of your language.

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025 Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025

Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025 News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025

News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025