From Dahl to Dostoevsky: how academia changed my relationship with reading

Nabiha Ahmed explores the distinction between academic reading and personal reading

I used to think reading a book was like an extremely satisfying hot shower, but for the mind. It was a way to cleanse myself, to spend time alone, then turn back to reality feeling like the best version of myself. Reading meant not exploring a world I wasn’t exposed to, but rather finding fragments of such stories in the life I was already living. Encounters with characters like Dahl’s Mr. Twit, and Blyton’s Saucepan Man, helped me to understand my feelings about the big world around me. I absorbed stories like water to feel happier in day-to-day life, or to alleviate any cynicism or dejection I was feeling at the time.

“I could temporarily remove myself from dealing with the world around me”

Reading was a portal through the pages, giving me a break from having to think about my life, yet also teaching me how to feel about reality once I’d put down the book. I could temporarily remove myself from dealing with the world around me whilst simultaneously immersing myself in a fictional version of it. Parts of me would be disguised: my boyish desire to break rules hid in Mr. Twit’s beard, and my fear of not being able to understand the needs of others was smothered in crockery with Saucepan Man. These kinds of books, typically fast-paced, were an easy way for me to learn what feeling meant; this was also why I felt like I couldn’t stop reading. It was a non-stop relay from cover to cover – that is, until we began our GCSE English course. Then, there was a dramatic shift in the way reading was presented to me.

During a Year 10 English class, our teacher took us to the library. I remember her saying something like, “top set should be reading either a classic, or an adult-level book outside class.” Would I no longer miss the type of books I used to read once I willingly tried with these more sophisticated ones? I had never delved into classic novels for pleasure, but I was told that they would assist in accruing a more ornate vocabulary. They were usually less concerned with action, and more concerned with style. These were books that would increase your reading age, but not necessarily ones that helped you understand the age you were at. The strain put on reading “academic” books was imposed on me not only by my school but also by myself. I convinced myself it was literary canon’s time to let loose. It was time to ditch the Dahl for good and bring on the Dostoevsky.

“Each tangential line felt like a cardio workout”

I left the library with The Great Gatsby that day. It made me read in a way I had never read before - like mental exercise, rather than a mental shower. Each tangential line felt like a cardio workout. And like a workout, sometimes it didn’t exactly feel good in the moment, but finishing made it all worthwhile. After finishing the book, I realised that reading academically, the kind of reading that teaches you how to think, was a realm that I had not delved into deeply enough up until that point.

The distinction between books that primarily made me feel and ones that taught me how to think became clear. Learning to think meant being able to find meaning in fictional realities that were important to others, and that it was fine if they weren’t my realities. It meant learning to find stimulation in a 150-page-novel where nothing really happens in terms of plot because it was occupied with the power of words, rather than the adrenaline rush I experienced in the action-packed stories I used to read. One helps you understand the validity of other people’s realities, whilst the other helps you work through your own. I found myself enjoying adult-level books, despite the fact that I didn’t understand half of the words at the time, and the reality that some of them were painfully slow. My “feeling books” were like an old friend I didn’t want to admit that I missed. But soon I realised that there was no shame in both types of reading; they were equally important in my personal development.

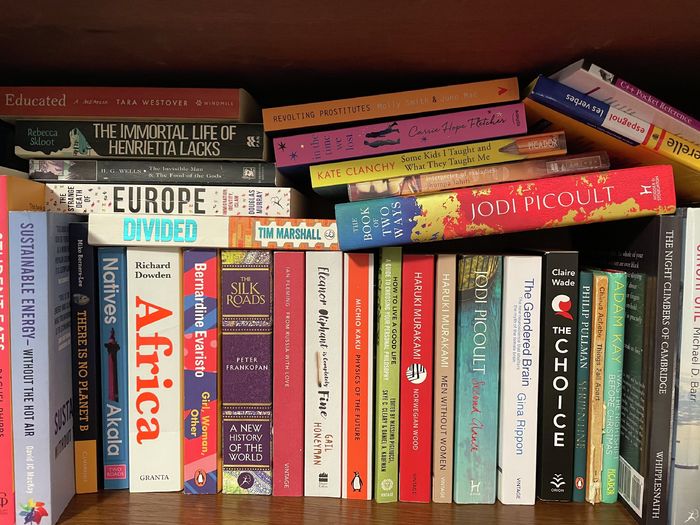

Reading for an English degree teaches you how to think - as George Saunders puts it, “a way of reading that evaluates a statement of truth, the way it behaves in relation to another mind (i.e the writer’s) across space and time.” Books that help you delve into the deepest part of your emotions (or ignore them) can be fun, but spending too long in those mental showers makes our skin shrivel up, to the point where we become unrecognisable to others. However, spending excessive time reading books deemed “academic” made me realise how important those other books were. Blending both together has helped me reap the best benefits of reading. Knowing that I can always spend an hour reading my favourite Harry Potter after a long day of Piers Plowman doesn’t mean I enjoy one over the other – it just means I’m training both my thought and feeling processes. One or the other in excess ruins the balance I have created between the two, and it’s great when I find a book that does both. I can read The Age of Innocence without letting it stop me from revisiting my own. I can enjoy mental workouts with reading, but I also give my mind the mental shower it deserves.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025