Ghost towns, or why you can never go home again

Columnist Jesi Bailey delves into memories of her first home and contemplates the transience of childhood identity

Two days into visiting my hometown, I texted my boyfriend: “Every time I come back to San Diego I remember why I don’t come back to San Diego.” He replied: “Lana Del Ray lyric sounding ass.” Both statements were true.

When I think of growing up in California, my mind seems to show me only the best memories. I create a montage of the perfect life: playing video games with my brothers, dancing in my yellow bedroom, carving the initials of my first crush into the tree in my front yard. My best friend Lauren lived in the house across the street from mine, and I never had to knock on her door before I entered. This city was the entire world and, within it, there was nothing I couldn’t know. I was defined, subject; if someone were to describe me, I knew exactly which words they would use first. Things were simply organised into boxes, the way they can only be for children who haven’t yet learned that loving something does not guarantee its permanence. In this world, everything was sacred, and I couldn’t have imagined it would not remain so forever.

“My childhood home was now impossibly empty”

By the time I decided to move away, I was under no such illusions. I was sixteen and terrified, feeling the foundations which I had spent my life standing upon crumbling. The fact that some changes had been inevitable did not make them easier to shoulder. My brothers had gotten older and moved out of the house, as did my father once my parents divorced. My childhood home was now impossibly empty, impractical and expensive for just me and my mother to be living in. Weeks after the “For Sale” sign was posted in our front yard, Lauren’s house got one to match. It was the final crack to shatter my rose-tinted glasses, and I fled at the first opportunity offered to me.

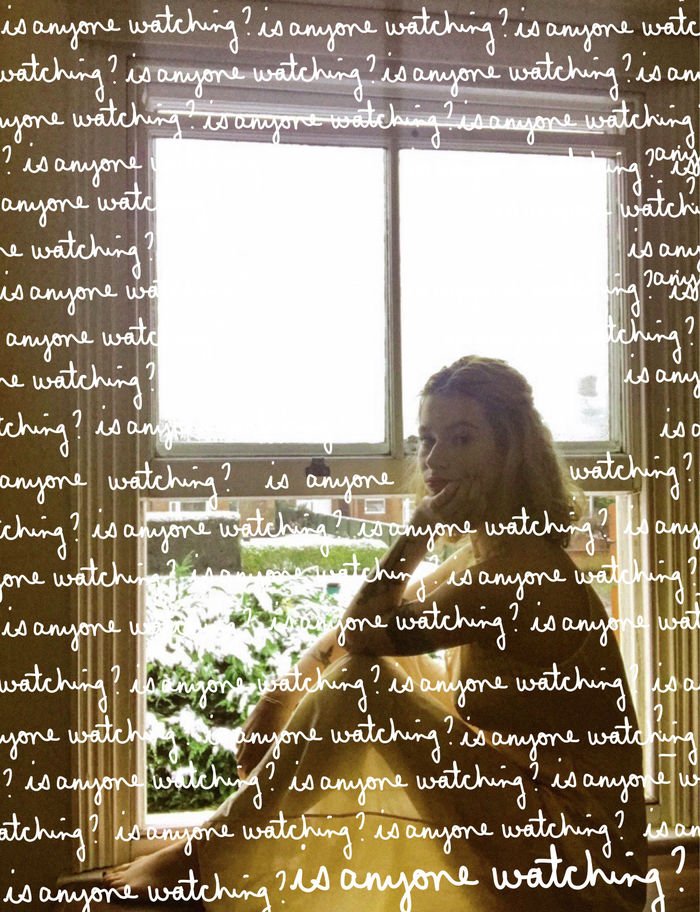

The fact is, I couldn’t stand to watch things end, and I ran somewhere new to make myself feel as if I had some modicum of choice in the matter. I spent years covering a city in my fingerprints, breaking bones and going on dates, all the while imagining that this act of worship would be enough to make these places holy and therefore protected. During my last night before leaving, Lauren and I convened among the packed boxes in my bedroom, attempting one last sleepover like we had grown up having. The walls had been repainted white for the sale of the house, and it upset me to look at. We laid on the floor and stared at the ceiling instead, spending hours silently watching the headlights of passing cars move across the room. They looked like ghosts.

“The people I love are kind, and they allow me the false pretence of my argument”

In December, I flew to California for my first visit in over three years. I don’t go often, and I don’t stay long – when I miss my siblings or Lauren too desperately, I cajole them into visiting me instead, arguing the superiority of adventuring to someplace entirely new. The people I love are kind, and they allow me the false pretence of my argument. But the terrible truth of it is that going back to San Diego only reminds me that I can’t go back home, that I can’t ever reinhabit the identity of the version of myself who lived there.

The girl who grew up in California is different from the girl who left it. The woman who comes back to visit is more of a stranger than ever. I know this isn’t inherently tragic; in many ways, I feel I’ve honoured promises I made to my past selves about who I would become. I moved to England. I got into university. I finally started seeing a therapist, and I don’t even lie to her in order to make her like me more. But I know there are also a great many dreams that I’ve let go of in the transition from my life as Her to my life as Me. In order to exist as I do now, I have had to grieve the possibilities of all of the other people I could have been and all of the people I no longer am. To revisit once-familiar spaces and find them alien and changed makes this starker than ever. It forces me to accept that the golden world I grew up in doesn’t exist anymore, that maybe there’s no way to go home again once you leave. Maybe we can never stop becoming new people.

On this last visit, Lauren and I went to look at our old houses and found that they weren’t our houses anymore. They belong to new families now, strangers who have their own arguments and traditions and lives playing out within those walls. My old tree, which previously stood large and imposing in the front yard, had been cut down. I wonder if they had problems with its roots like we did, or if they just didn’t like the look of it. I wonder where these new children will document their first crushes’ initials, and what colour they painted the bedroom I spent so many years in. For their sake, I hope it’s yellow. I hope their entire, wonderful world shines golden.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025