How hustle culture robbed me of my childhood

‘Work now, play later’ was a mantra very familiar to staff writer Zoe Olawore as a child; in this piece, she considers how it has caused her to relive those years in the now

Childhood is meant to be your glory days, I was told. Omniscient aunties and uncles would say that life, while I was young, was the best that it would get. And, though they said this in softer terms, life and its enjoyments would plateau once I was old enough to work a 9-5 and pay my taxes.

I am still aware of what an ideal childhood should look like. Literature and films are full of romantic depictions of childhood. One’s early years should be filled with imaginative play, nonchalance, and an engagement with the present rather than the future. But whilst I could successfully observe what childhood was meant to be, I never necessarily experienced it. Not because my younger years were terrible, nor because my small experience of adulthood has been great. It is because this rigid distinction between childhood and adulthood has never existed for me. My adolescence was not characterised by “life and its enjoyments” but rather by concerns about the job I would have, how hard I could work, the house I would own – if I could even own one – and how much money I would have.

“It became easy to forget that I was a child”

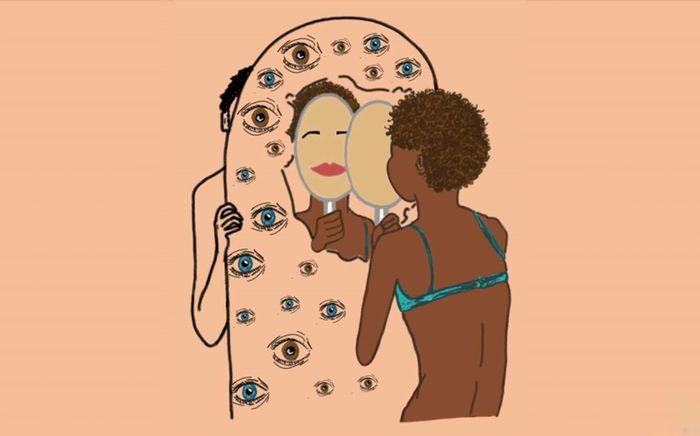

I found myself engaging with and supporting the myths of hustle culture from a young age. This is a culture where your career takes priority over other parts of the human experience like relationships. During early years, friendships should generally be characterised by a genuine enjoyment of being around each other, free from ulterior motives. In my mind, friendships were just a means for something greater — a looking glass for my future. They were, in fact, just another way for me to become “the best version of myself”. I binge-watched corny YouTube videos which described friendships as a determining factor of how much material success I could achieve. As a result of being parented by hustle culture, I commoditised the people around me. From Year 8 onwards, I developed the seemingly healthy habit of distancing myself from people who prioritised things other than work. It became easy to forget that I was a child: I saw childhood as this waiting room for adulthood — when my life would truly start. In primary school, my idea of small talk was asking my classmates what job they wanted to have in the future.

“My adulthood is now filled with the missing remnants of my childhood”

Hustle culture creates this impression that work should be at the centre of one’s life. Everything and everyone else is secondary. Because I internalised such a message, I would demean the value of just allowing myself to play. In secondary school, the career advisor’s office became my second home (and this is ironic because I am still not sure about what I want to do). After class, once the bell rang, I hastened to go to the library to do more work rather than spending time with my friends. In hindsight, it is clear that these habits I developed did not make me better. I was merely ignorant about the value of the present.

Being a daughter of immigrant parents also impacted the way I internalised hustle culture from a young age. My Dad, who migrated to England around the age of 23, was far too familiar with the rat race: success is scarce under capitalism and, unless you benefit from nepotism, intimidatingly competitive. As a result, my Dad was keen to ensure I would not lose. With a militant demeanour, he would repeat mantras like “work now play later”. In my Year 7 holidays, I was instructed to work six hours a day. While I scoffed at such suggestions, adopting this habit felt inevitable. Later when I was revising for my GCSEs I prized myself on how hard I worked — despite the majority of this work being futile.

So, while my glorification of hustle culture tainted my childhood, I am cautious to not let it take control of my adulthood. Despite receiving the dreaded comments that I had ‘changed’ once I'd done this, I was nonetheless eager to create a life that was truly mine. This meant resting from work when I was tired rather than pushing myself and perceiving this as a sign of strength. I began to pursue mental wellness once I realised that my contentment was more important than my achievements. Perhaps the biggest change was when I started to dedicate time and effort to my relationships both familial and platonic. Quite ironically, my adulthood is now filled with the missing remnants of my childhood.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025