‘At best negligent, at worst malicious’: Students on double time

Varsity uncovers the unnavigable process behind ‘double time’, Cambridge’s little-known alternative to intermission

A toxic idea has permeated this University: that study is meant to be ruinously hard. That it is normal to work until 2am, then get up at 7am and start all over again, trapped in a torturous, academic Groundhog Day.

If you have a chronic illness or disability, that can be impossible. The rate of production Cambridge expects is often not viable for someone with chronic fatigue, mobility issues, learning disabilities, or mental health problems. Add the endless hospital appointments and health related admin, and suddenly juggling the daily reality of their conditions and their Cambridge workload puts many disabled students at risk of burnout – or even worsening their illness.

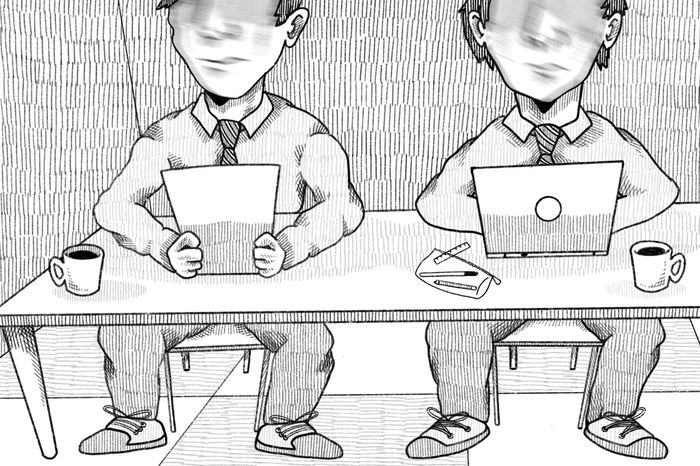

Extension to Period of Study (EPS), known colloquially to students as ‘double time’, is a little-known provision the university offers for disabled or unwell students. It allows the candidate to continue with their degree by spreading the workload of, for example, three years across six.

Part of the Adjusted Mode of Assessment (AMA) process, it is intended for students “where standard examination access arrangements to the standard mode of assessment do not adequately address the specific, substantial disadvantage experienced by a disabled student.”

Richard was told there was “no point applying for double time” as they would be rejected

The application for any AMA is comprised of medical evidence and application forms, and is made by the student’s college to the Exams Access Mitigation Committee (EAMC). It is then discussed at one of their meetings, and a decision is rendered.

Take one look at double time support forums, however, and you will find disabled students hanging by a thread, turning to those who have made it through the process for information that the University should be providing.

Some students I spoke to felt they had been urged not to talk about their experiences, or feared repercussions in the form of rejection of future applications. Almost all asked to remain anonymous. Some even later retracted their statements.

Their desperation is evident. I spoke to Richard (not their real name) about their experiences with the EAMC. Having spoken to staff for help, they were told that there was “no point applying for double time” as they would be rejected, despite significant evidence of disability.

Since graduating, Richard has been diagnosed with autism and ADHD. These diagnoses could have eased their experience of the AMA process, but there was simply no route available to pursue a diagnosis.

Richard was told by support staff that despite being “very obviously autistic, they couldn’t do anything to help.” Approaching the EAMC about alternative arrangements, such as coursework, they were met with further baffling resistance: “The primary concern of a faculty chair was that a reasonable adjustment to my exams – removing the timed element – would place me at an unfair advantage compared to other students.

A report published in 2020 found that “neither staff nor students were usually aware of double time”

“He repeatedly cited the need for parity as a reason to reject my requests, which is ironic since the reasonable adjustments are intended to attain just that.”

Dani, a student who was granted EPS, highlighted the challenges that they faced even after their application was accepted. They found that each year they had to have their application re-approved, and go through the entire process anew.

For Dani, this was incredibly frustrating. They had been chronically ill since their teens, with no sign of recovery, yet even this wasn’t enough to qualify for permanent arrangements. Going through the entire process over and over again was “a waste of time and energy, causing unnecessary stress”.

A key element of the frustration regularly experienced by disabled students who wish to pursue some sort of AMA is the lack of awareness of the details of double time – or even simply its existence – among university staff.

A report published in 2020 found that “students with long-term health problems were usually offered either full time study or intermission, and neither staff nor students were usually aware of ‘double time’”. This is despite double time’s positive reception: “Were double time an option, 70% of respondents considered themselves likely or more likely to be able to finish their degree”.

The report recommended that “all staff and students should be made aware of EPS as an option”. The EAMC claims it has implemented workshops for staff, but widespread awareness is still lacking.

“Behind all the admin and paperwork is a student who is really struggling”

Charlie’s experience echoes this. At first, their tutor told them that double time simply didn’t exist. Several months later, their tutor finally uncovered a document mentioning double time “on the last page and in tiny writing”. Charlie had developed chronic fatigue syndrome at the end of their second year; they put in an application in July and were informed of the EAMC’s verdict – approved – three months later.

They were comparatively lucky. After waiting six months for their application to be finalised and processed, Sophie was told that it was too far through the year for double time to be put in place. Instead, the EAMC recommended that they be granted exam access arrangements that had missed the point of their application, and they ended up having to apply for allowance to progress.

The waiting period is another issue that crops up consistently in my conversations with double timers. Students are left for months with no answer, not knowing what their future looks like. On top of this stress, they are expected to continue working at a rate detrimental to their health.

This isn’t an accidental quirk in the system; it is deliberate. As the 2022-23 guidelines for AMA applications states: “until the point of approval, the student should continue their study without any changes”. Students such as Sophie are left with no choice but to intermit, forced into an option that is in no way tailored to their needs.

In their role as SU double time officer, Charlie recalls many more students who were forced to intermit or drop out due to the process being “unnavigable”. Their verdict on the EAMC is damning: “at best, negligent; at worst, malicious.”

Cambridge is meant to be intellectually stimulating. It should not also be physically debilitating and mentally ruinous. Intellectual stimulation does not have to mean to utter exhaustion. We are conflating academic challenge with working ourselves into the ground.

Improvements in training and an overhaul of the system would, ironically, also make life easier for the university. With fairer treatment, there are fewer cases calling for review. With better informed staff, decisions can be made faster, at a lower level.

I contacted the students who had kindly spoken to me for this article a few days after our interviews, and asked them what they would say to the EAMC if they got the chance. The responses ranged from despairing frustration to inviting dialogue and better communication between all those involved.

As one applicant summed up, “I did not choose to become disabled, but you did choose to be a part of the EAMC. I would urge you all to consider the impact your decisions have on others.” Or in the words of another: “Behind the admin and paperwork is a student with a disability or long-term health condition who is really struggling.”

All students’ names have been anonymised at their request.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025