Cambridge commies or student sell-outs? The legacy of the University’s left-wing tradition

Claire Gao investigates the legacy of Cambridge’s left-wing tradition within student politics.

It’s the 1930s, and five students and fellows are recruited at Cambridge, embarking on their journey to eventually becoming spies for the Soviet Union and claiming their infamous “Cambridge Five” moniker. Flash forward eighty years, and the King’s College Student Union votes to take down the communist flag that has hung in their bar since 2004, home to where the future Soviet agents often had meetings. While the symbolic hammer and sickle may be gone, left-wing ideologies still thrive at the University.

It is no secret that Cambridge’s student demographic has long been dominated by the privileged and “bourgeois” classes. King Charles for instance, tried to join the Cambridge Universities Labour Club (CULC) during his time here. Cambridge’s reputation for being the more progressive of the Oxbridge pair leaves it vulnerable to allegations of champagne socialism, a stark contrast between lifestyle and ideology. Even the aforementioned spy ring, who passed on British intelligence to the communist Soviet Union during the Cold War, were composed of Etonians and Pitt Club members – some actually radicalised by Eton history teacher “Red” Robert Birley, I’m told by Andrew Lownie, biographer of spy Guy Burgess.

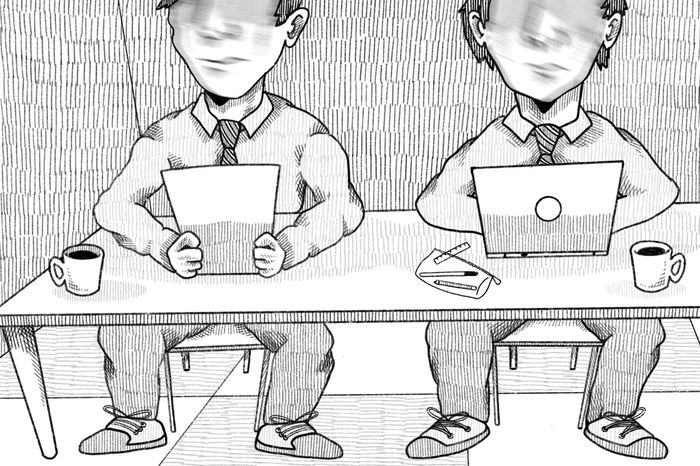

Today, student socialists face new criticisms of their ideological purity in the form of “briefcase socialism”. The term was coined by student Hassan (timestamp 38:00) at former Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis’ talk at the Cambridge Union. They tell Varsity that it describes “the phenomenon of Cambridge students who will protest against big corporations and businesses and talk about ‘capitalism and its ills’ and then at the same time contribute towards those businesses by taking internships or jobs at those corporations”. It feels particularly rife at Cambridge, which seems to funnel its students into cushy finance jobs.

“It feels particularly rife at Cambridge, which seems to funnel its students into cushy finance jobs”

Perhaps Cambridge leftists of today are less likely to be recruited by the KGB, but the wide umbrella of “the left” means that there inevitably will be a disparity between career choices, as the heads of various left-wing student organisations in Cambridge all recognise. I chat to the co-chairs of CULC, Katie Heggs and Lauren Tucker, and co-founder of the Cambridge University Solidarity Forum, Alex Horan.

They do acknowledge the existence of “those who decide to go from the Labour doorsteps to investment banking” (Katie) and “communists who will end up working for Slaughter and May” (Alex). However, the first-year communist to third-year LinkedIn warrior pipeline is certainly not a universal one, and while Alex notes that for some “diehard Blairites” and “welfare capitalists”, “you would absolutely expect [them] to go into corporate work” which aligns with their beliefs, Katie remarks that most of the former CULC co-chairs that she knows have gone to work for the Labour Party, civil service and journalism. Marxist Society members might utilise the society’s relationship with the revolutionary Socialist Appeal.

“We can’t expect everyone to be an activist – we all need to survive”

But Alex maintains: “We can’t expect everyone to be an activist – we all need to survive.” In recognition of wealth disparity and our existence within capitalism, I notice an agreement among left-wing student politicians in favour of social mobility: the view that for many, studying at Cambridge allows for “opportunities their parents could never dream of. That might mean working for a large corporation, or working for a not-for-profit. In the midst of a cost of living crisis, I have respect for those who choose either – as long as they keep their Labour Party membership!” (Katie). People contribute to social change in whichever ways they can, and Lauren suggests perhaps the critique of briefcase socialism “undermines the progress of student socialism”.

While representation in left-wing student politics has drastically changed from the monopoly of public school Old Boys, Katie says that “more female and enby voices are always welcome (especially those with northern accents).” The scene can be divisive and factional, and a former student and cabinet minister allegedly told CULC co-chairs that the Club was as, if not more, factional back in their day. But Lauren encourages more people who “feel that in any way you don’t belong in student politics” to get involved and get their voices heard.

Student politics clearly is a lively and active part of life here, but perhaps for the silent majority, it is little more than drunk debating that ignores tangible problems outside of the student bubble. For others, membership fees, significant conservative influence and “gender-critical” speakers frequently given platforms make the scene inaccessible. Cambridge is by no means a commune, but it has historically been and is still a breeding ground for radical thought and action.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025