Found in Translation: Thai mysticism and spiritual tourism

This week, Madeleine Pulman-Jones considers the place of cinema in Thailand, and the Western awareness of its culture

“A student ticket to Cemetery of Splendour, please.” As he printed my ticket, the man at the kiosk tells me, “The director said that it’s good if you fall asleep during his movies because it means that you’re completely immersed in the director’s vision. I saw the film at Cannes last year and it really stays in your mind.” Suddenly I am concerned that I may have just paid seven pounds to sleep for three hours.

“At least a part of their mysticism is lost once their image is so widely accessible”

Walking up the stairs to the screen I mull over the words of the ticket salesman. I once watched an interview with Charlotte Rampling who said that she had fallen asleep during every Tarkovsky film she had seen, but people have told her “it’s normal” to do so. I remember disagreeing intensely. I have just come out of an exam, and my brain is fried – I am the perfect target for a film designed to make me fall asleep. I hold on tight to my bottle of Lucozade and hope for the best. I did not fall asleep in that empty cinema that post-exam afternoon, but I certainly felt like I’d been dreaming.

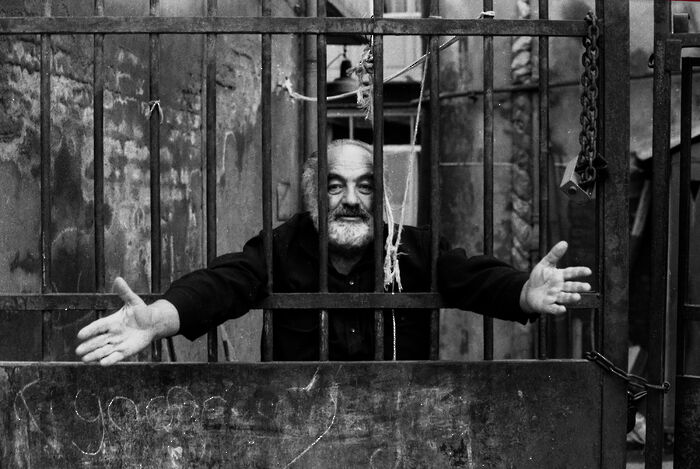

In urban mythology, it has long been rumoured that some cultures used to believe that a piece of one’s soul is taken away each time they have their photograph taken. As people, we have a degree of agency over how and when our photograph is taken. If we so desire, we might even attempt to ‘preserve our soul’ by ducking out of pictures and hiding from cameras. But what about places that possess a spiritual richness akin to a ‘soul’? For example, how many photographs of friends posing in front of the Wat Pho Temple in Thailand have we all seen over the past summer alone? Behind the smiling faces, the spires of the ancient temple stand somewhat awkwardly, like unsuspecting locals caught on camera in an on-location news report. This is not to criticise those who partake in ‘spiritual tourism’, but it is undeniable that, whether or not there is any spiritual significance to the abundance of photographs taken at these sites, at least a part of their mysticism is lost once their image is so widely accessible.

Enter Apichatpong Weerasethakul, ‘Joe’ to his friends (and the international cinematic community). Weerasethakul is indisputably Thailand’s premier film director. Over the past decade he has realised some of the most original and controversial work in arthouse cinema. Though Tropical Malady (2004), a spiritual interpretation of the romantic relationship between two soldiers in the Thai army, and Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (2010) won the Jury Prize and the Palme d’Or respectively at Cannes, Weerasethakul’s films are rarely widely released in his native Thailand.

“Weerasethakul’s lightness of touch in weaving the mundane with the spiritual is unparalleled”

The censorship controversy surrounding his 2006 film, Syndromes and a Century, which led Weerasethakul and other Thai directors to form the Free Thai Cinema Movement, prompted the Thai director of the Ministry of Culture’s Cultural Surveillance Centre to comment: “Nobody goes to see films by Apichatpong. Thai people want to see comedy. We like a laugh.” In a world where the right to agency of tourist hubs like Thailand over their own identity has been called into question by the prevalence of social media, Weerasethakul has become the international voice of Thai experience.

Cemetery of Splendour (2015) is Weerasethakul’s latest feature, and was screened to universal acclaim in the ‘Un Certain Regard’ section at Cannes. The film tells the story of a group of soldiers who, while digging up a building site, are stricken with a mysterious sleeping sickness and transferred to a makeshift hospital at a local school. The middle-aged Jenjira and youthful Keng are volunteers at the hospital. Keng has psychic abilities that enable her to communicate with the sleeping soldiers. She says that their disease has been caused by the spirits from the ancient cemetery of kings under the building site who are feeding off of the energy of the soldiers. Jenjira strikes up an unlikely friendship with Kitt, a soldier who has no visitors. Meanwhile, Jenjira is also visited by the spirits of two Laotian princesses, who appear to her in the form of well-dressed young Thai women.

Providing an example may be the only way of explaining what makes the film so mesmerising. One scene which is particularly moving is that in which Keng, possessed by the spirit of Kitt, washes Jenjira’s maimed leg. A scene that would otherwise seem sentimental or exaggerated is juxtaposed with the setting – a regular bench on the litter-strewn bank of a local lake. Weerasethakul’s lightness of touch in weaving the mundane with the spiritual is unparalleled.

He demonstrates the way in which we all engage with the spiritual in our everyday lives, while painting a portrait of Thailand as a country caught in limbo between its mystical, opulent past, and the inevitable onslaught of late capitalism (Jenjira and Kitt go for a surreal ‘date’ to a cinema in a clinically glamorous Thai shopping centre). The stunning temples, dramatic islands and white beaches we are sold as the essence of Thailand do not define the country, but rather inform its political and social evolution.

Cemetery of Splendour, or any one of Weerasethakul’s films, is more than worth watching – if only to experience a country so embedded in the subconscious of British youth in a different light

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025