Academy Honorary Award 2017: Le Bonheur is tainted by hypocrisy

While celebrating the incredible career of Agnès Varda, Madeleine Pulman-Jones finds a sense of discomfort in the sudden recognition of one of the finest living film directors.

“It was a big event, very serious, full of meaning and weight - but I feel that between weight and lightness, I choose lightness. And I feel like I’m dancing – the dance of cinema.”

“It is impossible to overlook the hypocrisy of the Academy’s decision to reward a filmmaker whose work they ignored for decades”

On 11th November 2017, paid tribute by Angelina Jolie and Jessica Chastain who she referred to as her “feminist guardian angels,” legendary French avant-garde director Agnès Varda became the first female director to win an Honorary Academy Award. Towards the end of her acceptance speech, eighty-nine-year-old Varda declared, “I feel like I’m dancing – the dance of cinema.” Eternal playfulness and sense of humour intact, standing with arms outstretched, draped in the swathes of her chiffon scarf, Varda looked less like she was dancing, and more like the human embodiment of one of Monet’s brushstrokes.

Varda is without doubt a spiritual foreigner on Hollywood soil. The land in which Varda and her films have always dwelt defies the definitions of both Hollywood cinema and French cinema. It is one of ‘lightness’ – one of possibility and colour, of weathered faces and wildflower, of fur hats in summer and people’s faces printed on wall-size posters. That the Academy have chosen to honour Varda is without doubt a hopeful step towards the recognition of women in filmmaking, but as Varda herself noted, this is “a side Oscar,” even going so far as to call it, “the Oscar of the poor.”

A lifelong leader of the anti-Hollywood European avant-garde, Varda is linked most strongly to the French nouvelle vague and more specifically to its intellectual, leftist, ‘Rive Gauche’ subset which included filmmakers such as Alain Resnais and Chris Marker. Varda’s debut feature, La Pointe Courte predates the two features generally accepted as the first films of the nouvelle vague, Resnais’s Hiroshima mon amour, and Godard’s seminal Breathless (he refused to travel to pick up his Honorary Oscar in 2010), by around five years, leading many to regard it as the true root of the nouvelle vague movement.

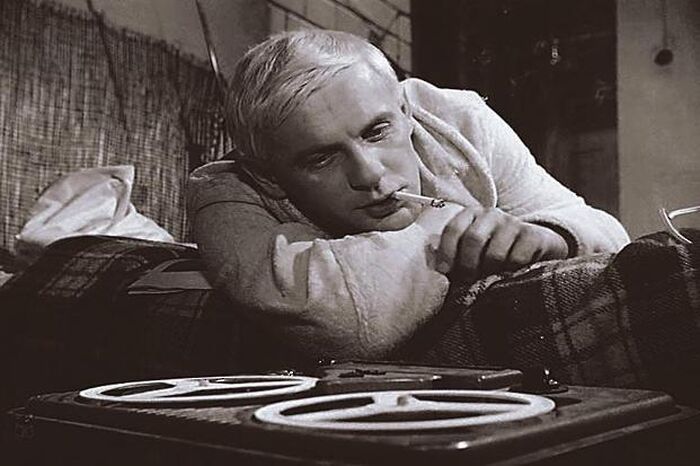

During the nouvelle vague, Varda made masterpieces including Cléo from 5 to 7 (1961) and Le Bonheur (1965). Since then, she has continued to make films that push the boundaries of narrative cinema, such as One Sings, The Other Doesn’t (1977) and Vagabond (1984), moving in later years towards documentary and installation art. Indeed, it was most likely her 2016 collaboration, with French artist JR, Faces and Places, a feature length documentary, which catapulted her back into the collective consciousness of the industry and led to this award.

In her 2008 self-portrait The Beaches of Agnès, Varda stated humorously that she, “tried to be a joyful feminist, but [she] was very angry.” Varda’s particular brand of feminist filmmaking is at once a call to arms to female filmmakers, and also a form of intimate portraiture. In Cléo from 5 to 7, Varda not only revolutionised French cinema by affording a woman the same attention and scope for existential questioning as her male contemporaries, but also feminised traditional notions of cinematic time by capturing an hour-and-a-half of Cléo’s life in real time. This preoccupation with the filmic expression of female lived experience has also been reflected in Varda’s encouragement of women to train as technicians and take agency over their own representation in cinema.

It is beyond question that Agnès Varda is a pioneering, iconoclastic director in regard to the fight for equal representation of women in the film industry, but in regard to her place in the cinematic canon, Varda is all-too-often defined by her gender rather than her artistic genius. Her honorary Oscar will no doubt alert a whole new generation to her inspiringly idiosyncratic cinematic world as well as her revolutionary feminist activism – which is hugely positive.

However, Varda herself had her reservations about the Oscar, saying in a recent interview with the New York Times, that “It’s ridiculous. I’m well known but still remain poor, with poor audiences and poor box office. [The prize] is like a consolation.” From Varda’s perspective, mainstream recognition in this form is perhaps unwanted. She highlighted in her acceptance speech her difficulties in finding financing for her ambitious and unconventional films, and it is impossible to overlook the hypocrisy of the Academy’s decision to reward a filmmaker whose work they ignored for decades, quite possibly in a bid to make themselves seem more diverse amid the #OscarsSoWhite and Harvey Weinstein scandals.

Of course, this may be an ungenerous interpretation of a genuine display of appreciation for a true master of the form, but one cannot help but question the sincerity of this award

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025

News / Unions protest handling of redundancies at Epidemiology Unit30 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025

Features / ‘Treated like we’re incompetent’: ents officers on college micromanagement30 December 2025 Science / Astronomical events to look out for over the break29 December 2025

Science / Astronomical events to look out for over the break29 December 2025