I watch, therefore I am: the rise of philosophical TV

Upon the release of Season 3 of The Good Place, Michele Sanguanini explores the prominence of philosophical shows

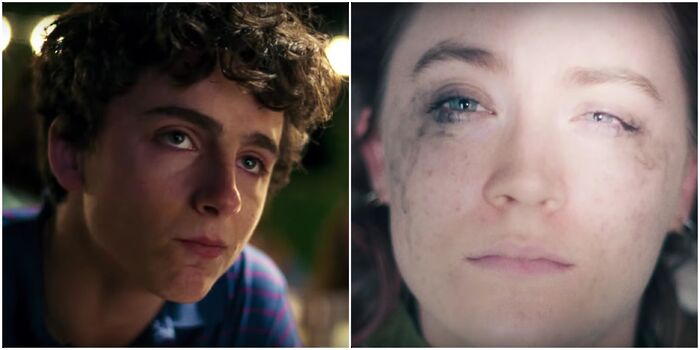

A wise man once wrote that you have to have a very high IQ to understand Rick and Morty. For that matter (and nothing really does), the same holds for The Good Place, whose third season is currently being released on Netflix, an episode a week. With its direct references to Aristotle, Kantian ethics and utilitarianism (yes, trolley dilemmas included), The Good Place is only the most outspoken of a slew of recent TV series with a focus on philosophy.

BoJack Horseman, another Netflix gem, is a dark tale of self-discovery and self-destruction. Its characters struggle to find happiness, a sense of belonging, or just some meaning in life. A further show dealing with existential questions is Rick and Morty, probably the most polished piece of epic fiction since Neil Gaiman’s graphic novel series The Sandman. Two absurdist anti-heroes travel across parallel universes, fighting against implausible creatures, fly-like humanoid bureaucrats and POTUS, because why not? As the lead Morty says, “Nobody exists on purpose; nobody belongs anywhere; everybody's gonna die. Come watch TV?”

Why is this rise in explicit philosophical messages in TV series happening? Is it a fluke in established trends of digital media content making? Or is it telling us something more profound about our society and the 'millennial' generation?

Easy jokes are intertwined with sharp and nihilistic statements on life and existence.

I like to think that we are living at the dawn of an era of disruptive creativity and deep interrogation of tradition, much like the end of the Belle Époque. Rick Sanchez is the digital Man Without Qualities, BoJack our Leopold Bloom. Easy jokes are intertwined with sharp and nihilistic statements on life and existence. In The Good Place, the almighty Judge (Maya Rudolph) who determines whether someone should be doomed to ‘The Bad Place’ for all of eternity is found binge watching NCIS and getting excited over her burrito. BoJack struggles with being given a free churro because his mum died – a story that resulted in an episode-length monologue from BoJack, taking place at the funeral of his mother.

It is attractive to explain the meme generation’s fondness of dark, self-deprecating, nihilistic humour with the perfect storm of environmental challenges, enormous global and local inequalities, and political uncertainty inherited from past generations. After all, retirement is probably a mirage, and we can't even be reassured that our quality of life will be as good as that of our parents.

However, something is missing in this story. In a sense, with tagging each other in content or sharing how volatile our experiences and emotions are, we are forcing ourselves to face existence in its own chaos and fascination. The baby boomers’ ethos of hiding the burden of existential pain and crisis control is neither valid nor pursued anymore. Hank Hill (King of the Hill) would stick all feelings of existential angst into a pit deep down in his stomach. Instead, we expose ourselves to the nihilistic content of dank memes or to the effect of wholesome pics: a digital-era re-purposing of the same feelings of sublime and connection with human misery that led to the first development of existentialism in the nineteenth century.

These two sides of millennials’ behaviour on social media are represented well in the contrast between the dark and cynical view of existence in BoJack Horseman and Rick and Morty and the somewhat optimistic attitude of The Good Place. Whereas the former two shows are distinctly nihilistic, The Good Place maintains an optimistic tone, despite the threat of being sentenced to eternal suffering. Life might be devoid of purpose; existence might be pain – however, what the main characters from The Good Place show us is that meaning can be found. It simply comes from caring from each other. Perhaps this is what stops BoJack or Rick and Morty from being too depressing – we may laugh at the cosmic meaningless of life, but in engaging with other fans and sharing these memes, we find meaning in each other.

Perhaps these shows, despite portraying life as meaningless and absurd, show us how to find a meaning in life after all.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026