World Cinema in 2020: No Longer the Underdog

Is it finally time for non-English language films to dominate mainstream cinema? Film & TV’s staff writer, Anika Kaul, discusses her top picks for a year which witnessed the release of some of the greatest international films of the century.

Last year, as theatres were forced to close their doors and the majority of filming came to a grinding halt, the cinema industry became one of many severely impacted by coronavirus. However, this disturbance was not reflected in the quality of the films released. Quite the opposite: from South Korea to South America, exploring topics as relevant and broad-ranging as sexuality and socio-political issues, 2020 will be remembered as one of the finest and most versatile yet for world cinema.

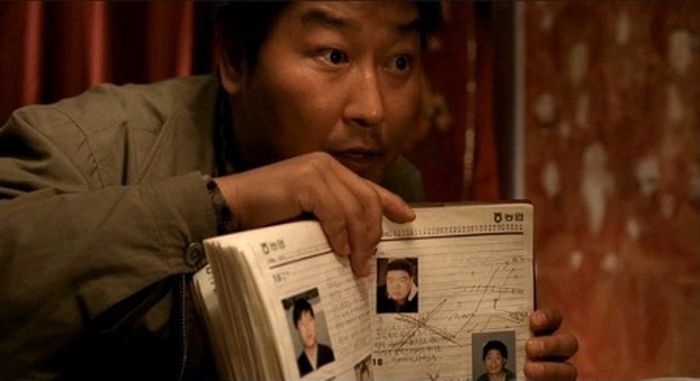

Parasite – Bong Joon-ho

Parasite’s performance at the 92nd Academy Awards was perhaps the most memorable moment in 2020 world cinema. Bong Joon-ho’s subversive film was awarded four Oscars, most notably and controversially being that of Best Picture. Certain critics (including the then-President of the United States) objected to the Academy’s decision, believing that a non-English-language title should remain confined to the category of Best International Feature Film. Appreciation for the unparalleled artistry of Parasite nonetheless overshadowed these condemnations. Alongside numerous accolades, it became film app Letterboxd’s highest rated picture.

"Bong Joon-ho masterfully captured the difficulties faced by the working class and the obstacles which prevent them from social and financial advancement."

Perhaps the reason for its extreme success was not only the stellar direction, cinematography and acting within the film, but also the socio-political messages it delivered. Bong Joon-ho masterfully captured the difficulties faced by the working class and the obstacles which prevent them from social and financial advancement. Through his distinctive tragicomic narrative, viewers were entertained by the antics of the Kim family whilst being confronted with the severity of the South Korean social divide: an effective juxtaposition attempted by many filmmakers, but achieved by few. Fortunately for audiences, Parasite wasn’t the only international film to subvert filmic and social mores this year.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire – Céline Sciamma

Despite the recent surge in titles centred on femininity and sexuality, an over-saturation of cisgender male directors has often resulted in the on-screen fetishisation and subsequent objectification of lesbian relationships (see: Abdellatif Kechiche’s Blue is the Warmest Colour). Céline Sciamma’s Portrait of a Lady on Fire overthrows this cinematic norm to depict a relationship between two multidimensional women from a female perspective, rejecting the male gaze which typically characterises female romance in film. While avoiding major displays of emotion and melodrama, the subversiveness of Portrait of a Lady on Fire rests in its subtlety. Its prevalent themes of representation and feminism are finely woven into the plot, ultimately creating a liberating effect rather than a didactic one. Although the film primarily excelled within the realm of French cinema, receiving prizes at Cannes as well as the César Awards, it was also recognised overseas, earning praise from critics in both the United Kingdom and the United States.

Bacurau – Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles

Unfortunately, many international films remain overlooked by the Western world, regardless of their quality. Such is the case of Bacurau, a Brazilian satire focused on political exploitation and oppression. In the film, civil unrest, historical tensions and economic strife lead to class warfare, which plays out through skillfully shot sequences of extreme violence. Directors Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles utilise these displays of brutality to illustrate the magnitude of the injustice faced by the poor. It is through its undiluted gore that the duo produce the film’s unforgiving anti-capitalist satire, exposing Brazil’s complex monetary and political problems.

"Filho and Dornelles reinforce the notion of cinema as a powerful political medium."

Viewers might interpret a vilification of the current Brazilian leader, Jair Bolsonaro, whose right-wing government has been accused of threatening human rights, and has even been likened to a dictatorship. This extremist environment has served to deepen the divisions of race, class and geography within the country, and by reflecting and commenting upon these issues through their film, Filho and Dornelles reinforce the notion of cinema as a powerful political medium. Even though Bacurau has been overlooked in the majority of the West, it was awarded the Cannes Jury Prize, outvying several anglophone films. It seems that, albeit gradually, non-English language films are finally gaining a well-deserved appreciation.

Titles from the USA and UK, dominating the film industry, are often regarded as some of the most progressive. Nonetheless, it is world cinema that repeatedly manages to confront tradition and break stereotypes whilst, decades-on, Hollywood still perpetuates the same beliefs and perspectives. From the backlash against Parasite’s Academy Awards victory and the dismissal of other international pictures, it is evident that the Western world, its industry and audience alike, continue to withhold a prejudice against world cinema. Until as recently as 2020, the Academy Awards still referred to international films as ‘foreign’, implying a normative and superior Western narrative while associating non-English language films with ‘otherness’. Though the category has now been renamed ‘international’, it begs the question of when world cinema will stop having to tackle attitudes of xenophobia and racism. Hopefully not for long, as 2020 has shown that world cinema is becoming increasingly successful; critically, financially and creatively.

Ultimately, each of these films is revolutionary in its own right. The often straight, typically male and almost always white narrative which governs anglophone cinema is overdone, and perhaps in these times of great exhaustion and trauma, in which days seem to repeat themselves in Groundhog Day fashion, a change is not only welcome, but necessary.

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025 Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025 Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025 News / Cambridge Union to host Charlie Kirk and Katie Price28 April 2025

News / Cambridge Union to host Charlie Kirk and Katie Price28 April 2025