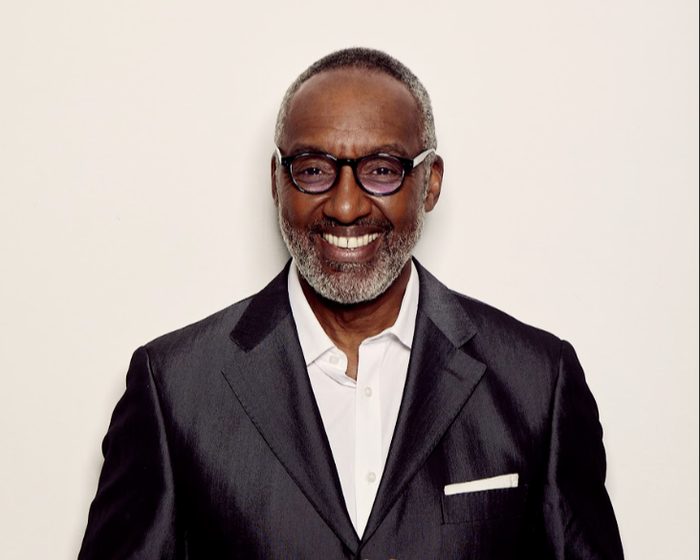

‘I try to speak for those who don’t have a voice’: Lord Simon Woolley, Principal of Homerton

Lord Simon Woolley discusses transforming British politics, tackling racism, and his mission to improve social mobility through education

Lord Simon Woolley’s political and social activism has been transformative for British society. As the founder and director of Operation Black Vote, Woolley is credited with creating monumental improvements in Black and minority ethnic representation in British politics that have indelibly changed our politics for the better. Becoming a member of the House of Lords in 2019, and the Principal of Homerton in 2021, making him the first Black man to head an Oxbridge College, he tells me his new objective: to “inspire a generation to believe that they can do great things.”

Lord Woolley has not let the grandeur of his new position affect his character. Logging on to our Zoom call a few minutes late from his Homerton office, because he was busy making his PA a cup of tea, Lord Woolley begins by telling me how his childhood shaped him.

“I want to continue to fight for justice, equality, for dignity, for people who have less power”

Fostered and later adopted by a white couple, and growing up on a council estate in St Matthew’s, Leicester in the 1960s, Woolley recalls: “when you live in a council estate that’s where you live […] back then there wasn’t the stigma of living in social housing as there is today, caused by politicians who too often deem those in social housing as feckless and lazy.” Drawing from his own experience, Woolley strongly asserts, “Nothing could be further from the truth: working class meant that people were working and had social housing – and they had dignity.”

Woolley describes his awareness of socio-economic inequalities from a young age, “we aspired to have money […] because we knew it would give us agency over our lives.” He recounts how he learned resilience early on in life: “racism was alive and sometimes kicking […] we had to fight our corner physically. I guess those years have made me aware today, in part, that I want to continue to fight for justice, equality, for dignity, for people who have less power.”

Leaving school without A-Levels, instead getting an apprenticeship as a car mechanic, Woolley moved into sales and then advertising. Woolley left his job in order to pursue higher education through an access course, starting his undergraduate degree at Middlesex University in English Literature and Spanish at the age of 27. Woolley explains that part of his motivation for pursuing education later in life was that “I thought that people who had been to university, particularly Oxford and Cambridge, were better than me. I think a lot of working-class people might think that too, but nothing could be further from the truth.”

Joyfully, Woolley tells me his other main motivation: “I knew that it could be a wonderful journey of learning […] The goal was for knowledge, not for a first.” In particular, Woolley cites his travels to Latin America during his university years in the early 1990s as “one of the greatest learning curves of my life.” “I’d seen people there prepared to die for their cause. So I knew at home I wouldn’t get shot and I knew I wouldn’t get kidnapped, so I felt powerful and I had no excuse not to do this.”

“I’d seen people there prepared to die for their cause...I had no excuse not to do this”

Quickly joining Charter 88 after his return, a British pressure group that campaigned for constitutional reform, Woolley tells me how it became clear that “Charter 88 were audacious in ‘we can change the system’ and I saw that. What they couldn’t do was do anything for Black people.”

Woolley co-founded Operation Black Vote (OBV) in 1996 to lobby political parties to vie for the Black and minority ethnic vote, after realising that their participation in elections could change the outcome of marginal parliamentary seats. Woolley proudly explains the organisation’s name: “in the 70s and 80s, police interactions with Black communities would be called Operation Bluebird and Operation This or That […] we turned that on its head to empower us”.

OBV is non-partisan, a decision that Woolley stands by, especially when looking across the pond. “African Americans in the USA put all their eggs into the Democratic basket and look where they are now. You have the likes of Donald Trump, who cares not one jot about Black people, in part because they have no skin in the game in regards to who they select and who will elect. We thought we want all the parties vying for the non-white vote, and if they all vie then they know they’ve got to have greater representation.”

Operation Black Vote’s impact has been monumental, helping increase the number of Black, Asian and minority ethnic MPs from 7 in 1996 to 66 in 2023, making the UK one of the most representative democracies in Western Europe. However, if Parliament were truly reflective of the 16% of our population from minority ethnic backgrounds, this number would actually be 104 MPs.

Woolley highlights the significance of having an Asian Prime Minister in the UK, “not that Rishi Sunak would afford any credibility to Operation Black Vote to his pathway to the top office, but let me tell you, without us he wouldn’t be there. And that’s not an arrogant assertion. It’s a matter of fact.” However, Woolley admits that he does sometimes feel “saddened” that “some of those politicians […] are lording policies that their own parents would be prejudiced by if they had been in place at that time.”

From 2018 to 2020, Woolley worked with Prime Minister Theresa May as the advisory chair of the world’s first Race Disparity Unit. Woolley describes the Unit as “groundbreaking”: “it’s the first government in a Western democracy that has a unit that looks at disparities and seeks to close them […] if you’ve got the political will then you’re closer.”

Woolley has been a fierce critic of the 2021 government-commissioned Sewell Report that denied the existence of institutional racism, stating that it “is used too casually as an explanatory tool.” He tells me: “during that time the nation was at a critical moment in its history. You had COVID-19, a devastating impact that laid bare racial structural inequalities as never before: housing, teaching, jobs, health […] including the biggest factor that if you’re Black or Bangladeshi you were six times more likely to die. So that, alongside the death of George Floyd, caused the tectonic plates in our society to be shook.” He summarises the report’s message: “The narrative was we’re dying because we’re inferior, we are poor because we’re work shy. It was heart-breaking to see a Black man front that.”

Turning to discuss his experience and work as a member of the House of Lords and as Principal of Homerton, I ask Lord Woolley how he deals with being part of an establishment that he has spent his life trying to challenge. He jokes: “I like a challenge, don’t I? [...] I think that the short answer is, be true to yourself, respect the institutions, but it mustn’t preclude you from wanting to change them within […] I try and use my agency to speak for those who don’t have a voice.”

Woolley has been open about the impostor syndrome he sometimes feels as a member of these institutions. However, he is aware of his importance in these spaces: “I can bring a lived experience that adds to the Cambridge experience and that gives others who look like me and others who have come from a council estate that this place is for them too, not just to survive, but to thrive.”

“I can bring a lived experience...that this place is for them too, not just to survive, but to thrive”

As the first Black man to head an Oxbridge College, Woolley tells me, “I’m not weighed down by it, if I’m honest with you I feel blessed. However, I know it means I mustn’t mess up […] Sometimes I feel like it’s a lonely place. I still feel frustrated that not all my colleagues get the enormity of being Black in an institution like Cambridge University. But for the most part, they’re wonderfully generous, and I couldn’t have asked for greater support. Although sometimes I think ‘argh’ we could do this quicker, better.”

A key focus of Woolley’s, as Principal of Homerton, is to improve social mobility through access to education. Cambridge’s Foundation Year is something that he is particularly passionate about, having had a similar route into education earlier in his life. “It’s fantastic! I just think that we have to begin to look at how we view potential talent, because too often we do it in a narrow parameter: triple A*s, which some communities will benefit from by having a more privileged education than others.” However, Woolley has even higher aspirations: “I think it shouldn’t just be the Foundation Year. I would argue we need to do much more work upstream in primary schools and in schools, coming to Cambridge is about not just being smart but it’s about understanding the code […] If you don’t know any of these you can’t get past go.”

When asked what he hopes his legacy at Homerton will be, he replies, “I often get asked that question and I don’t think I’m driven by legacy. I’m driven by acting today, doing the best that I can, and empowering others in this space.”

Why did you take the job as Principal of Homerton?

Time is everything and I’ve worked 25 years in politics. When Homerton came calling I thought this is the time for the next chapter.

What is your favourite part of the college?

Oh, the grounds. We have the best grounds here in Cambridge. I said to the students when they get a bit frazzled, because they’ve got to read so many books for their essays, go on a walk in the orchard, see the different seasons, join the gardening club.

The best and worst thing about being head of a college?

To be in a privileged position to inspire. Raising money to keep the lights on.

If you had to be the master of another college, which would you choose?

I wouldn’t.

What would you say to your successor in this role?

Be you, own you and enjoy it.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025