‘How do you live a wise life?’: understanding education with Min Jin Lee

Ella Howard discusses writing, identity and metaphysics with award-winning writer Min Jin Lee

Like so many others, I first became enamoured with Min Jin Lee through reading her novel Pachinko, swept up in the multi-generational history of the struggles and survival of a Korean immigrant family. In the years since, I have gone from citing Lee in my university application to attending her Ra Jong-yil lecture at Cambridge, culminating in the full-circle moment of emailing my carefully worded interview invitation.

Meanwhile, Lee has earned an array of fellowships and prizes, with Pachinko voted one of the New York Times “100 Best Books of the Century” and recommended by both Barack Obama and Queen Consort Camilla. Her debut novel Free Food for Millionaires opens with the line ‘competence can be a curse’, but for the award-winning author it appears to be anything but.

Yet despite such meteoric success, Lee’s career has not always been smooth sailing: she published her debut novel in her late thirties after quitting a job in corporate law. Speaking on her unconventional route into the industry, Lee told Varsity that “I have experienced a great deal of failure as a writer and in other parts of my life”, [but] I do not believe that I am an imposter.”

“In order to be an imposter, there must be the original. I think each of us can be original”

She continues on the subject of “alleged imposter syndrome” describing it as “oversubscribed and reductive”. “I think Theodore Roosevelt may have said ‘comparison is the thief of joy.’ In order to be an imposter, there must be the original. I think each of us can be original.”

For Lee, this “original[ity]” is “informed by genetics, physiology, culture, family history, and received education.” She is particularly interested in the last influence, noting that although “education may overcome deficiencies, …I do not believe that an educated person is always a moral person”. Indeed, Min Jin Lee explains that in her upcoming novel, American Hagwon, she is “trying to understand the purpose of education”.

Lee tells me that “the more I research, the more I understand the questions I wish to address. One of my questions for my current novel, American Hagwon, is: how do you live a wise life? This question seems right for my age. I am 55 years old. I have several of these kinds of metaphysical questions, and usually, my answers form a thesis statement. Like any thesis statement, it is an assertion, and it is both arguable and provable.” Lee has a habit of using the opening line of her novels as thesis statements for the entire book, giving each one a clear and succinct purpose.

“I try to take difficult and hard-earned knowledge of scholars and attempt to integrate it into fiction”

When it comes to writing the remainder of her novels, research is just as necessary. “I find the anti-intellectual sentiments in advanced economies/democracies to be nothing short of shameful and foolish,” says Lee. “I read a great deal of scholarship, and I am in awe of what scholars have achieved and attempt to achieve.” Such scholarship provides an essential foundation for Lee’s own thoughts. “I try to take difficult and hard-earned knowledge of scholars and attempt to integrate it into fiction. I do not know if I am successful. No matter what, I know that learning from courageous scholars has transformed me,” she adds. Given the immense value Lee places on research, it’s not at all surprising that she wishes “that the important academic scholarship of numerous disciplines was more available to ordinary people… It is troubling that scholarship, which demands extraordinary sacrifices, is so improperly or rarely disseminated. Academic scholarship can save lives.”

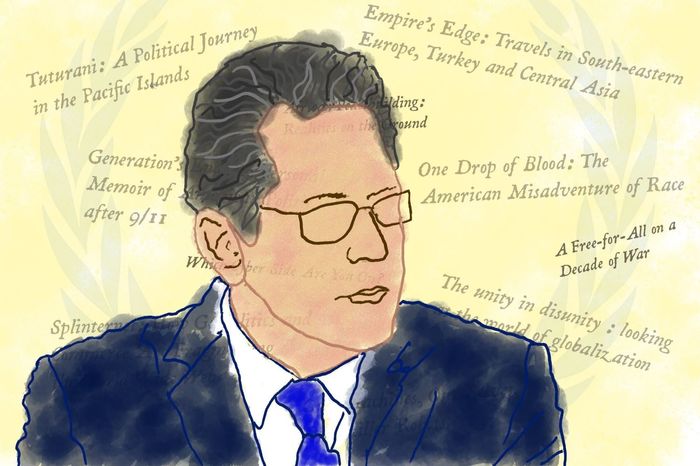

‘It was like a license to ask questions’: Scott Malcomson on his journalistic jaunts

Of course, this is equally as relevant for the student as it is for the writer; regardless of its purpose, education is a privilege. I am happy to hear Lee’s passion and admiration for academia mirrored in my own, though I am unsure if my supervision essays are quite on the level of saving lives just yet. There are other similarities between both kinds of writing: describing her writing process, Lee tells me that she “does not write everyday” preferring to “write for several hours, take a break, then write again when I can” whilst doing “everything [she] can to avoid distractions.” Although she claims not to have a “typical writing life,” the struggle she describes is one relatable to many a university student I’m sure. Min Jin Lee ends our questions with a few lines of advice, directing new writers to “choose the important over the urgent.” She emphasises: “Do the work. Do the work as well as you can. Never waste the reader’s time. Consider deeply what you want to say.”

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025 Features / In-person interviews through student helpers’ eyes20 December 2025

Features / In-person interviews through student helpers’ eyes20 December 2025