Lessons from lockdown: relationships

Navigating the new terrain of virtual relationships is difficult, but it’ll help prepare us for life after Cambridge, says columnist Jess Molyneux.

If you’re not currently spending a disproportionate amount of time re-evaluating everything you thought you knew about how friendships function, then your exams probably haven’t been cancelled. Lucky you: the rest of us are being put through the trial of connection catastrophes and getting to grips with too many new platforms.

One enjoyable thing about the pandemic’s reduction of all extra-household socialising to video calls is the way I’ve been forced to sit down and have one-on-one conversations. Rather than just expecting to find my friends in my kitchen or snatching a catch up in the library, a surplus of time coupled with heartache for Cambridge and everyone in it has made me carve out social time in ways that the pressure of term rarely allows.

Personally, calls easily beat the more constant but always staggered contact of a message conversation; they make you interact in a more focussed and absorbing way than we’re used to when talking to people who we see every day, let alone who we occasionally message.

“Lingering behind even the best of catch-ups as you hang up, is that bittersweet feeling of having recaptured a piece of Cambridge life only to let it all go again.”

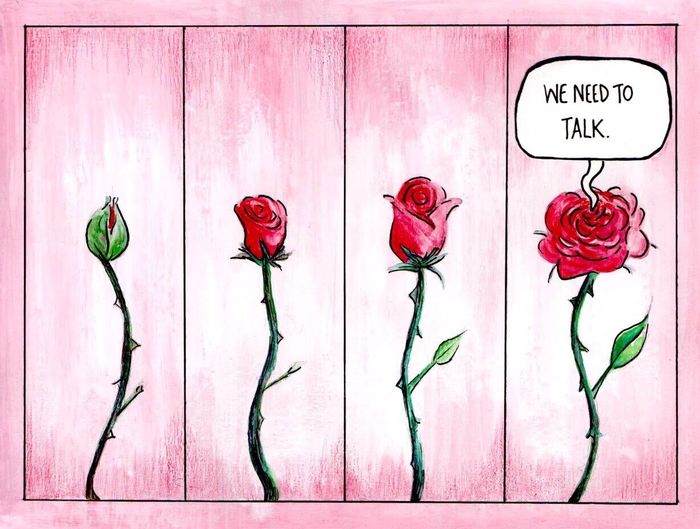

Whether you get into deep and meaningful territory or just share the mundane details of the past few days, calls at this time can make us feel more connected than ever, because we make the effort to set aside an hour or more, to ask about each other’s projects, family life, or mental health statuses, for example. This way of staying in touch resembles, more than anything, the dating which begins and sustains romantic relationships: a great way, then, to get to know old friends and new ones better.

But it’s not all pixelated smiles. Some people hate the pressure of keeping up a one-on-one call, even with close friends, especially when no one has much big news these days. And sometimes you just want to get lost in the group chatter, to be absorbed and passive but present in a way which isn’t possible over Zoom.

Gone are those lecture anecdotes which you catch when you run into someone in the college cafe, those unscheduled dinner dates with your housemates, that flying banter as you pass someone dashing to a supo. What can’t be replicated is shouting across the room to someone at pres, switching between two conversations either side of you at formal, getting distracted by a wandering friend in the library.

“People become placeless, and this layer of connection, integral to a lot of friendships, dissolves.”

Instead of shifting in a single day between all those different versions of yourself which come out with different friends and in different groups, the variety of interaction which perks you up as you go about your business is siphoned off into more defined but less constant ‘I’m on the phone!’ time slots.

Instead of having people you have dinner with every day, people you have coffee with once a term, people you study with, people you live with, people you see at the Union or at the theatre or on King’s Parade, and all the almost imperceptibly varying aspects of your personality which each of them brings out, you have people you call and people you message, with any finer distinctions provided only by differing frequency. People become placeless, and this layer of connection, integral to a lot of friendships, dissolves.

It isn’t something that we’re unaccustomed to, having spent at least first year conducting long-distance relationships outside of term. But what got us through, then, was looking forward to a real-life reunion which was never more than five or six weeks away. Facetiming was a stop-gap; message threads were resurrected only to dissolve upon real contact time; a train ride for a weekend house-hopping in London wasn’t illegal.

But now the temporary techniques of friendship have become semi-permanent, and lingering behind even the best of catch-ups as you hang up, is that bittersweet feeling of having recaptured a piece of Cambridge life only to let it all go again.

It isn’t just that absence makes the heart grow fonder. Figuring out how to sustain relationships when absence is the norm makes you realise which ones really matter and why. Though it’s a little heart-wrenching to consider, what this global crisis is giving us second years (and freshers) is a taste of what it’ll be like when we graduate and are flung into the far corners of the real world, no longer concentrated in Cambridge.

It’s giving us the chance to test what saying goodbye will look like, the time to practice letting go - and learning how to hold on - before we have to do it for real. And it’s hopefully showing us that if our friendships can stand the test of a global pandemic, they’ll certainly make it through graduation and out into the big wide world.

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026

News / Cambridge academics sign open letter criticising research funding changes22 February 2026 News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026

News / Student and union protesters hold ‘Trans Liberation Solidarity Rally’ 24 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026

Features / Beyond the porters’ lodge: is life better outside college?24 February 2026 Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026

Theatre / Footlights Spring Revue? Don’t Mind if I Do!25 February 2026