Why it’s important to be a feminist in our relationships

Subtler patriarchal conventions seem insignificant in the face of global gender inequality, but they can spark conversation about the feminist agenda, says columnist Jess Molyneux.

Content Note: This article contains a brief mention of disordered eating, mental health in relation to body image, domestic violence and sexual assault.

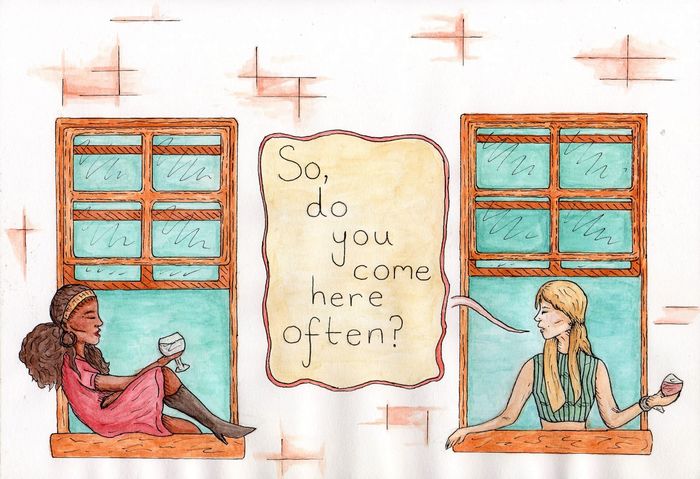

It’s interesting to wonder what a guy who insists on paying the bill on a date with a girl thinks about his relationship to patriarchy. He probably isn’t analysing it– but for most girls who date guys, insistence beyond a polite offer is one of those uncomfortable crossroads, with the choice between upholding the feminist principle or submitting to residual patriarchal convention.

It seems insignificant when we look at the broader project of gender equality outside this paradigm of a heterosexual, cisgender, consensual relationship between a probably white, probably middle-class man and woman. But I think this act, which plays outdated gender norms and is inextricably related to past and present economic inequalities, can be a useful starter for thinking about the broader, intersectional feminist picture.

“You don’t always want to become the ‘shouty feminist’ because what you’re calling out isn’t extreme, active misogyny or abuse and is often done out of ignorance rather than wilful oppression.”

That white middle-class men in the UK are able to insist on footing the whole bill has a lot to do with the global gender pay gap and the time men around the world aren’t spending doing 75% of unpaid domestic and care work. Many financially secure women feel comfortable standing their ground on paying for themselves, but that doesn’t mean that all women can escape more sinister financial coercion and abuse.

Part of the reason it feels important is because it’s an entry point. With male friends and boyfriends, it can feel like your responsibility, because you’ve got a unique point of access, to fill men in on periods, on violence as a gendered problem, on the body image issues and eating disorder pandemic which you can’t solve by telling a girl she’s beautiful.

But with someone you’re attracted to or in love with, you don’t always want to rant, to ruin a moment by explaining why something’s not okay. You don’t always want to become the ‘shouty feminist’ because what you’re calling out isn’t extreme, active misogyny or abuse and is often done out of ignorance rather than wilful oppression.

Take the example of sex: you know what equality and balance should look like, but asking for what you want in the moment can feel more selfish than empowering. The application of principle in practice is complicated, not by a lack of strength or a secret desire to take advantage of the perks of inequality, but by the fact that love and attraction complicate your priorities.

So you don’t always take the opportunity to apply a corrective to patriarchy, but the little pinpricks remain whether you act upon them or not, and it can sometimes feel like they’re separating you from the people you love.

This is a problem for a relatively privileged subset of women who are lucky enough to be able to opt in and out of engaging. But, firstly, this doesn’t mean their challenges under patriarchy, because less urgent, are invalid or irrelevant: experiences of sexual assault or disordered eating, for example, need our attention.

“The imperative to be part of the change only comes with making the connection between that bigger picture and the closer-to-home experience of lingering patriarchy.”

They might not be the global issues at the top of feminism’s agenda, but that doesn’t mean that men (who aren’t themselves campaigning to end global period poverty or sexual assault of refugees by border guards) shouldn’t hear about them.

But secondly, and more importantly, I don’t see how men will ever be able to play the role which they need to play in ending patriarchy, in all its trivial and more sinister manifestations, until they acknowledge the impact it’s having on the women closest to them.

The bigger global problems can be easier to see – very few people would think that “feminism has gone too far” in countries where it hasn’t secured basic legal equality. But the imperative to be part of the change only comes with making the connection between that bigger picture and the closer-to-home experience of lingering patriarchy.

“Feminism also inevitably alerts us to problems which aren’t solved yet, and which our interactions can contribute to furthering or resolving.”

And it’s not just privileged women – but anyone who loves the person who commits intimate partner violence, who has been enraged by white Western beauty standards, who has been victimised by homophobic toxic masculinity – who will feel that real equality and deconstruction of gender norms would improve their most important relationships.

There are so many ways in which feminism helps us to have much healthier and more meaningful relationships, to have better sex, to be okay on our own. But feminism also inevitably alerts us to problems which aren’t solved yet, and which our interactions can contribute to furthering or resolving.

Individuals can’t take down the patriarchy from inside their own relationships. But a willingness to see the impact of gender inequality in those relationships, and to use them to start conversation, is a good place to begin.

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025

Features / Cloudbusting: happy 10th birthday to the building you’ve never heard of30 March 2025 News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025

News / Uni offers AI course for Lloyds employees30 March 2025 News / Caius clock hand returned nearly 100 years after student prank31 March 2025

News / Caius clock hand returned nearly 100 years after student prank31 March 2025 News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025

News / Ski mask-wearing teens break into Caius accommodation27 March 2025 News / Write for Varsity this Easter31 March 2025

News / Write for Varsity this Easter31 March 2025