Why is ‘lesbian’ still a dirty word?

This Pride month, Miranda Stephenson considers the reluctance of many to claim the word ‘lesbian’ for their own, and why ‘gay’ may not by the ultimate umbrella term for all

Why is it that, amidst all the exciting new victories for the LGBT community, all the flamboyant explosion of pride month celebration, ‘lesbian’ remains a stigmatised word?

Perhaps this stigma’s very existence will come as a surprise to some. From 1983 to 2020, British support for same-sex relationships has more than quadrupled. When I told my mum my idea for this article, she wrinkled her brow and asked me, “Is there any shame around the word ‘lesbian’?” If you consider the experience of lesbians themselves, it would certainly seem so. For want of professional statistic evidence, I surveyed 120 women-loving women and found that, whilst just 33% felt “very comfortable” with calling themselves lesbian, but a far more significant 70% were “very comfortable” being labelled gay. One woman commented that ‘lesbian’ sounds “a bit slimy”, whilst multiple wrote that the word evoked “disgust”. So, okay then, women who love women prefer to be called ‘gay’. A rose by another name smells much, much sweeter. Why? The very fact I had to resort to my own data indicates a wider failure to engage with this issue.

"When it doesn’t stink of bitter misandry, ‘lesbian’ seems dirty and embarrassing, quite alien from the earnest, loving relationships that many queer women dream of."

For starters, ‘lesbian’ and its various derivatives remain common insults for girls who fall foul of their peers’ approval. This is nothing new. At the peak of Second Wave Feminism, campaigners were demonised as man-hating, bra-burning, communist lesbians, gleefully plotting society’s destabilisation. What’s more, these supposed lesbians were vilified as so horrifically ‘ugly’ (read: non-heteronormative), that no self-respecting man would consider them marriage material anyway. In fact, despite lesbians’ active involvement in the feminist movement, prominent activists like Betty Friedan were highly lesbophobic themselves.

Nowadays, gender equality has progressed considerably, but the old, lesbian stereotypes still haunt the popular psyche. After finding out my sexuality, a friend’s mum commented, “Oh, but she’s actually quite pretty!” on a photo that I’m in. Years ago, when my forays into self-experimentation manifested as an awkward mullet, my relatives’ remarks were similar. “Be careful to always wear make-up, or people will think you’re a boy! Or worse… You’ll look like a lesbian.” Back then, my parents forced me to wear a ridiculously oversized hair-bow. After all, no lesbian would wear something so girly… right?

At the same time, ‘lesbian’ also carries radically opposite associations. Over the past decade, ‘lesbian’ has been Pornhub’s most popular category: the word is slick with performative sensuality, decidedly inappropriate for polite society. Needless to say, young girls first discovering their same-sex attraction are hardly clamouring to identify with this hyper-sexualised world of scissoring, threesomes, and dispassionate ‘orgasms’. When it doesn’t stink of bitter misandry, ‘lesbian’ seems dirty and embarrassing, quite alien from the earnest, loving relationships that many queer women dream of.

"‘Lesbian’ has been historically hijacked, warped to distortion by the male gaze: no more. "

With this being the case, the less-officious, gender-neutral ‘gay’ has become something of a safe haven. That should be fine. It’s a preference, after all, and the specifically non-male ‘lesbian’ carries so much baggage. The problem is, upon closer consideration, using the same label for gay men and women has proven more harmful than first appears.

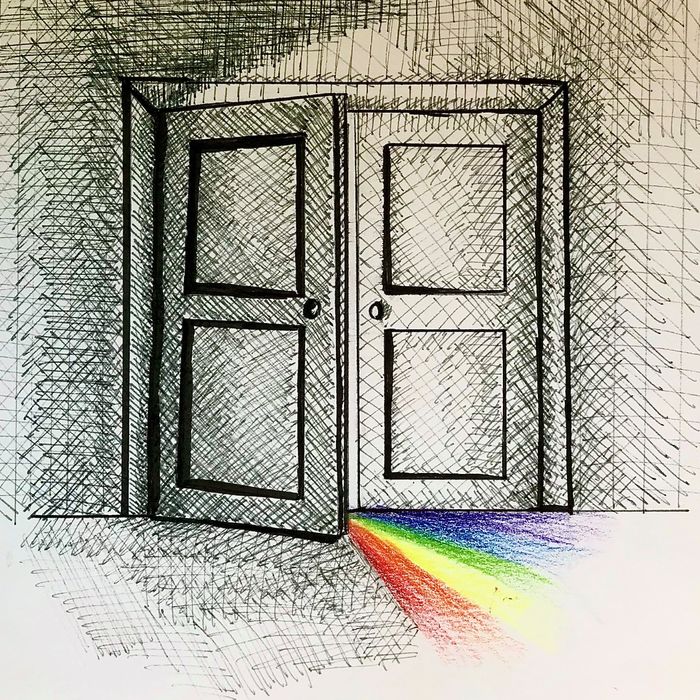

‘Gay’ may be welcomed as an umbrella term for the wider LGBT community, but it also remains primarily used for gay men. Such an androcentric ‘normal’, extended to represent the whole community, is equally seen in the rainbow flag which dominates Pride, and all the rainbow-branded merch that entails. Whilst other sexualities have their own, separate flags, gay men do not. ‘Rainbow’ means everyone, and ‘rainbow’ means gay men. Somewhere along the line, ‘everyone’ and ‘gay men’ have started to converge. This is a very good thing for companies keen to jump onto the pride month marketing bandwagon, who both exploit and propagate the notion of ‘gay as norm’. All they have to do is plaster a tawdry-looking rainbow on a couple of their products, and boom! The LGBT community becomes their cash-cow, with minimal money wasted on design.

It hasn’t seemed in activists’ interests to complain. Thanks, in part,to this brave new world of rainbows, LGBT people have shot to visibility. Stonewall’s scholastic partnership means that the poster “Some people are gay. Get over it!” has been shocking parents and educating teenagers since 2007; ground-breaking queer movies like Call Me by Your Name attract devotees of every sexuality. However, as ‘gay’ slopes towards its grave as a schoolyard insult, it’s tempting to wonder whether ‘lesbian’ might have won a similar fate, had activism not centred around the de-facto male-focused word ‘gay’. It is telling that, of the top 10 all-time highest-grossing LGBT films in the US, every single one of these is about gay men, or a male same-sex relationship. There is a deceptive paradox in claiming that ‘gay’ refers to everyone regardless of gender, without remaining open to further debate: for if ‘gay’ is theoretically an umbrella term, in practice, the benefits and discourse it generates are predictably cis-male oriented. This tide of male-centred, ostensibly ‘gay’ media sweeps gay women’s own, lacking representation neatly under the rug.

What’s in a name, then? The balance between representation and comparative invisibility. This pride month, if we are to be truly proud, it seems about time that lesbian love is reclaimed in its own right. ‘Lesbian’ has been historically hijacked, warped to distortion by the male gaze: no more. The media’s ghoulish and slandered ‘lesbian’ has held her vampiric court long enough. It is time to acknowledge the word’s classical, romantic roots. An ancient poet once let her love for other women be known so exquisitely, lesbians today take their name from her home.

It’s time to shake off the stigma.

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025

News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025 News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025

News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025 Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025

Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025 Sport / Cambridge celebrate clean sweep at Boat Race 202514 April 2025

Sport / Cambridge celebrate clean sweep at Boat Race 202514 April 2025