Curing bicultural seasickness

Lucia Trivass-Berlanga learns to navigate and re-engage with her fragmented cultural identity

Remember that painfully awkward moment on the first day of school, when your teacher invariably asks the class to introduce themselves with a fun fact? I always settled on the somewhat bland ‘I’m half Spanish’ as my go-to answer. This is a fact (my mother is Spanish, but I was born in England to a British father), although I question whether it was really fun for anyone, except maybe for the primary school teacher who seemed to enjoy telling me how exotic this made me.

It explained my weirdly pronounced name (the ‘c’ is pronounced as a ‘th’ sound), my lengthy double-barrelled surname, and my biannual trips to Spain. As clunky as it might be to explain, it felt like an innate part of who I was.

When I went to university, I found this previously secure understanding of my identity shattered. Separated from the Spanish domestic environment my mother had spent my childhood curating, all the aspects of my spanish identity – the food, the language, the books – seemed to shrink in their significance to my daily life. Most horrifically, whilst I grew up having dinner at 9pm, I came to enjoy eating at 6pm.

“How do I translate ‘supervision’, or ‘college formal’? How do I explain what I’m learning about?”

Talking to my mother on the phone, the language posed new difficulties: not just from my creaking fluency after disuse, but from words that I didn’t even know how to translate. How do I translate ‘supervision’, or ‘college formal’? How do I explain what I’m learning about? I barely understood Hobbes and Weber in English, so my attempts to translate this into a language which had been languishing in the back of my mind were pretty pathetic. I somberly noted the symbolism: this new chapter in my life was one I found literally “untranslatable” into Spanish, thus representing the entrenched isolation of my present self from the culture that I had once thought defined much of my life.

I felt like a total disappointment to my mother and my country. I might be ethnically Spanish, have a Spanish passport and speak the language pretty much fluently, but if I could be so suddenly disconnected from the culture by moving 90 miles from my childhood home, could I really claim it as such an important part of my identity?

I cringed as I thought back to Freshers week, when I had introduced myself, as usual, as ‘half British, half Spanish’. It now sounded so fraudulent. Maybe I had come across like one of those weird Americans who are obsessed with being 1/16th Cherokee, desperate to appropriate cultural differences in an attempt to make themselves seem more interesting and unique. ‘Spanish’ felt like a label I no longer had a right to claim, and maybe never ought to have had.

“‘Spanish’ felt like a label I no longer had a right to claim, and maybe never ought to have had”

Before coming to university, I had never stopped to examine the meaning of being ‘half Spanish’, and the obvious implication of partialness in that clunky phrase. I was explicitly telling everyone the incompleteness of my Spanish identity, but never really realising it myself. I had naively thought of myself as both wholly British and wholly Spanish, with those complete identities fused together in a perfect, multicultural multiplicity of identity. I was left with a more unsatisfying self-perception, which saw my Spanishness as fundamentally limited by my isolation from my family, and thus merely a frail and faltering expression of biculturalism.

This agonising, once it had passed through the mental doldrums of my overthinking, eventually led to some conclusions about the nature of cultural identity:

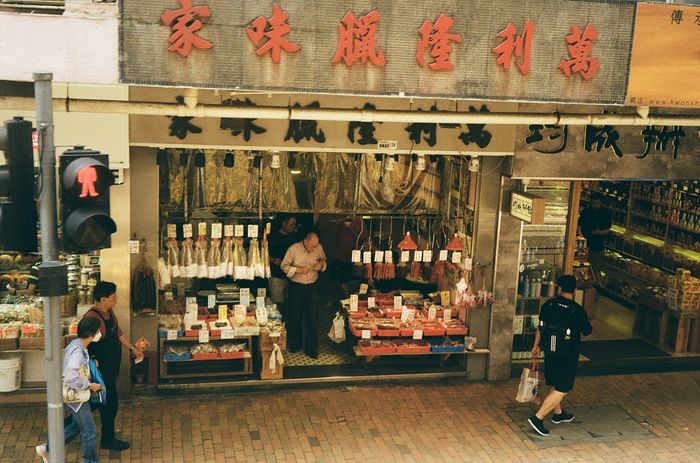

1) Culture is practical as well as principle-based, and has to be acted on. If you feel guilty and disingenuous calling yourself Spanish because you feel disconnected from your heritage, it is probably your responsibility to re-engage with the culture you grew up with. Listen to some 80s Spanish pop music, read some Lorca and Becquer. Decorate your second year room with Spanish flags and dried Iberian meats, in the style of your grandparents’ rustic homestead.

2) There is no handy checklist of cultural references and customs practised that can quantify how Spanish I am, and thus dispel the guilt I feel about underappreciating my mother’s heritage. Belonging to a culture doesn’t need to be forensically proved to imaginary cynical strangers. If experiencing a culture is fundamentally entwined with being part of a family, this should be seen as a positive reflection of the love shared between family members, rather than provoke agonising as to whether one’s experience of culture is fundamentally restricted and narrow.

3) Reconciling these two conclusions might lead to less wallowing and aimless pondering of my fragmented cultural identity, which is, frankly, a very sad use of my time - time which would be better spent wallowing about a more diverse range of preoccupations.

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Science / Astronomical events to look out for over the break29 December 2025

Science / Astronomical events to look out for over the break29 December 2025