Teenagers run the music industry. Here’s why.

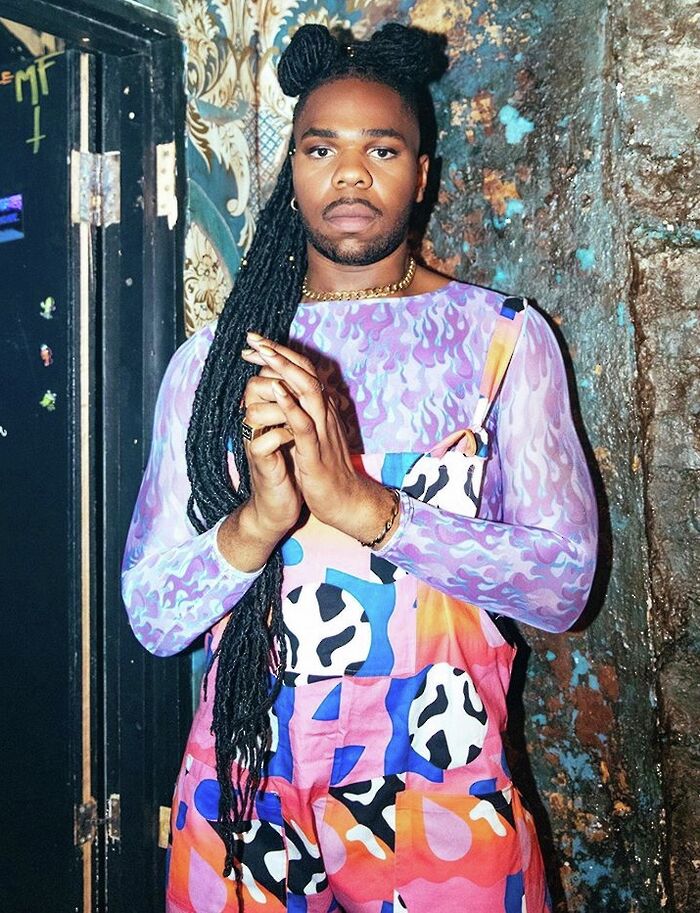

Vulture Music columnist Kwaku Gyasi comments on how the internet has made fame more accessible to younger artists

The music business has always had to constantly work around new forms of media and technology to sustain itself. This has been very evident in the past few decades, as the rise of piracy, iTunes and streaming in rapid succession have completely upended the industry, not only changing the kind of music that artists make, but how consumers engage with it. As with any technologically-driven field, millennial and Generation Z digital natives, who have always had to work the hardest to prove and promote themselves, have been able to effect real change — and make real money — that even bigwigs at record labels have tried to study and replicate. It is clear that the Internet has given rise to unparalleled innovation from the most consistently overlooked communities in various forms of entertainment, and the parallel phenomenon in music is seeing black teenage rappers game a system made to lock them out and deny their position as tastemakers.

Artists and labels have been aware of how great a role the internet has played in promotion for a while now. Internet dance challenges have launched many songs to the top of the charts and added a lot of names to the never-ending list of one-hit wonders -- artists like Baauer, whose 2012 single ‘Harlem Shake’ spent a month at #1 because of people’s inexplicable desire to record themselves convulsing off beat while dressed in elaborate costumes. But the purchasing power of young people has only been deliberately harnessed by a select few musicians with their ear to the ground, who understood exactly how to use virality to capture adolescent attention, and the first to do this was arguably Soulja Boy. In a bid to become the first viral rapper at the age of 17, Soulja pushed his debut single ‘Crank That (Soulja Boy)’ relentlessly, taking advantage of its accompanying dance craze and popularity on then-budding social media site, YouTube. The song went on to reign atop the Billboard Hot 100 for seven weeks, earn a Grammy Nomination for Best Rap Song and reportedly sell 15 million ringtones, in an era when that was a legitimate metric of a song’s success. While many of his predecessors in the genre decried the song as an omen of the “death of hip-hop”, he had successfully tapped into a market that had long been ignored and that he was still a part of: children and teenagers.

But there is a reason why his ability to maintain a relatively successful career for a few years, especially as a previously unknown Georgia teenager who made his beats on Fruity Loops, is not just because his fanbase was overwhelmingly made up of minors. His thick accent and crisp, clean production was part of a wave of hip-hop that was then and is now heavily ridiculed: mid-2000s Southern rap. A sector of the audience that propelled ‘Crank That’ to the top of the charts likely made fun of his slurring Southern accent even while unable to resist the distinctive steel pan instrumental. We’ve seen this ‘ironic’ appreciation applied to the flurry of dance crazes (including but not limited to: the shoot, the whip, the nae-nae, the floss, the dab, the milly rock, the dougie, the quan and the whoa) which entered the mainstream during or after the golden age of Vine three to five years ago. These dances tended to spring from Black American communities, and like ‘Crank That’, a fresh-faced teenage rapper would make a danceable song with instructional lyrics, and cute home videos of children performing the song would follow. As is natural, celebrities pick up on these trends (which had so much cultural power that it was reported a start-up company was cranking them out), we get bored of them, and they travel through layers of mockery and irony until they end up known as Fortnite dances, associated with affluent pre-adolescent boys and torn from their originators.

But the youth of today understand how to exploit semi-ironic, non-committal attitudes common on the Internet. This is most easily exemplified by 20-year-old rapper Lil Nas X, who in the span of a year turned himself from a tweetdecker into a global sensation. Known previously under the alias @NasMaraj, he would make viral tweets which reached hundreds of thousands of followers, and in the replies he would draw attention to his SoundCloud. When he released ‘Old Town Road’ at the end of 2018, he would edit together meme videos of characters like Shrek dancing to his song ‘Old Town Road’ and joke with his growing fanbase about getting Billy Ray Cyrus to feature on the song (which inexplicably happened) and the trend of performing to the song with the caption #yeehaw spread like wildfire on the app TikTok, well before he had even become a recognisable name. The unsupervised children who run TikTok are rarely taken seriously (as comedians or even as genuine tastemakers), but Lil Nas X said in an interview with Time Magazine that “a lot of people will try to downplay it, but I saw it as something bigger.” The strength of suburban teens’ semi-ironic enjoyment of the song was powerful enough as to make ‘Old Town Road’ unavoidable for the greater part of 2019, going as far as breaking an all-time Hot 100 record for weeks at #1.

Lil Nas X, however, is far from the first artist to harness meme culture to get his music out there -- he just managed to whittle it down to a science. Ever aware of his evolution in the public eye from hip-hop’s crybaby to the preeminent rap artist of this generation, Drake rode the memes from the ‘Hotline Bling’ and ‘In My Feelings’ music videos all the way to the bank. Mariah Carey’s 2008 diss track ‘Obsessed’ started to climb back up the charts this summer, all because TikTok user @reesehardy7 posted a video of herself crying and dancing to it, triggering the creation of the #ObsessedChallenge. ‘Roman Holiday’, the haywire opening track from Nicki Minaj’s second studio album, experienced its biggest streaming week ever seven years after its release after Twitter stans breathed new life into it with bizarre edits. We live in a world where if enough lonely kids in a social media group chat find something funny or awkward or even embarrassing, livelihoods can be impacted.

That being said, TikTok and Twitter can breathe life into songs that are seen as more than trends or fads. Carey specifically experiences this repeated surge of interest in her music every winter. In January 2019, her holiday classic ‘All I Want for Christmas is You’ cracked the top 3 of the US all-genre chart, reaching an all-time peak, and there is every chance that it could top the chart this Christmas, twenty-five years after its debut, off of the strength of streams.

The impact of streaming is impossible to ignore, considering it has essentially upended what it is that popular music charts actually measure. With pure single and album sales, the only way for us to track a song’s popularity would be to see how many people buy it every week. But streaming has made music available to so many more people — especially young people and hip-hop fans, two groups which had been historically misrepresented by the charts — and tracks listening patterns as opposed to purchasing patterns. Minaj, in the midst of advocating for streams to count towards album sales in 2015, commented on the implicit exclusion of hip-hop consumers by overlooking the impact of streaming, noting that “the music business doesn’t really seem designed to reward our culture with the sales and accolades we deserve.”

Now, egalitarian might not be the word to describe this newfound inclusion, as artists have repeatedly drawn attention to the fact that waning music sales have robbed many musicians of the possibility of making much profit from their work. That being said, streaming, as well as the rise of the internet as a tool used both to create and share music, has had the unintended effect of making the music industry more accessible, as now the power to decide how and when to release music rests more in the hands of creators, and not of record labels.

Overall, it is inspiring to see the Internet work its magic on the music business. It means a lot that younger and younger artists see Lil Nas X or Billie Eilish in control of their careers, or recognise Mariah Carey as the legendary vocalist and songwriter she is, as well as being the Queen of Christmas. It is important that we acknowledge the innovation that so many young artists have pursued in trying to engage the public, because I didn’t think it was possible to write so much about the effect Soulja Boy had on the music industry. Anyone who wants to impact culture has to understand how the most marginalised continue to work around their circumstances to make spaces that shut them out pay attention to them, because that’s how we open ourselves up to the best that artists have to offer.

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge’s tourism risks commodifying students18 April 2025 News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025

News / Cambridge student numbers fall amid nationwide decline14 April 2025 News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025

News / Greenwich House occupiers miss deadline to respond to University legal action15 April 2025 Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025

Comment / The Cambridge workload prioritises quantity over quality 16 April 2025 Sport / Cambridge celebrate clean sweep at Boat Race 202514 April 2025

Sport / Cambridge celebrate clean sweep at Boat Race 202514 April 2025