Sir Rodric Braithwaite: Back in the USSR

Josh Kimblin meets Rodric Braithwaite, the UK’s former ambassador to Moscow, to hear his account of how the Soviet Union collapsed

It takes a certain type of dry, diplomatic wit to refer to the collapse of the Soviet Union as an “interesting time”.

Sir Rodric Braithwaite (a Christ’s alumnus) served as the United Kingdom’s ambassador in Moscow between 1988 and 1992. During that time, he witnessed Mikhail Gorbachev’s faltering attempts at reform, the dissolution of the Union, and Boris Yeltsin’s early presidency. “Interesting” is quite the understatement.

As ambassador, Braithwaite knew all the period’s politicians personally. I ask what his relationship with Gorbachev was like. “I met him all the time,” he replies breezily. “I still meet him. I last saw him about three years ago – and my opinion of him hasn’t changed. Ambassadors are not meant to get involved in the politics of the country, but we did. And we were great Gorbachev supporters.”

“Having spent a long time with him, and his most intimate staff, I came to the conclusion that he was a very nice man. That’s not something you say often about the leaders of the Soviet Union.”

Braithwaite’s enthusiasm about Gorbachev is far from universal. The former president is lauded as a peace-maker in the West but reviled as a nation-breaker in Russia.

“Some of the reasons for why he is reviled domestically are very understandable,” Braithwaite explains. “Gorbachev oversaw the collapse of the Soviet Union; it’s easy to say that he was directly responsible. When he began the process of reform in the 1980s, through glasnost and perestroika, he didn’t know how he was going to end it. He unleashed forces which outran him.”

“But this is an unfair criticism. Nobody in Russia could have neatly started and concluded reform of that scale. The changes which Gorbachev sought were going to produce unforeseeable and unintended consequences, irrespective of his leadership. That said, I understand why the Russians have turned on him; they suffered very greatly during the 1990s.”

“Gorbachev was a very nice man. That’s not something you say often about the leaders of the Soviet Union”

Long before public opinion rejected Gorbachev, he was loathed by the conservative wing of the Communist Party. This animus culminated in the abortive August 1991 coup, in which a group of diehard Soviet apparatchiks concocted a plan to seize control of the government and reverse Gorbachev’s reforms. I ask Braithwaite about his experience of the attempted coup.

“My wife’s experience of it was that she was on the barricades outside the White House [site of the Supreme Soviet of Russia] with the defenders on the night of 20th August, when the coup leaders were about to seize the building.”

“Ambassadors’ wives are not supposed to do that; ambassadors certainly aren’t! I was being thoroughly responsible, writing telegrams and saying, ‘There’s something very odd about this coup; I think it will fail.’ That was obvious from the start.”

Braithwaite continues: “The coup leaders believed that popular opinion was so deeply levelled against Gorbachev that they would rally around his deposers. But they didn’t. When the generals saw that and realised that victory would be bought only with enormous bloodletting, they pulled back. The man who gave the order for the tanks to leave central Moscow was the Defence Minister – the same man who had ordered them in. That rather proves the point.”

The decision not to use force was merciful but possibly unexpected. Only two years before, the Chinese government had crushed pro-democracy dissenters in Tiananmen Square. The Soviet Union had done the same in Hungary in 1956 and in Prague in 1968. What forced a different decision in August 1991?

“This is entirely unprovable, but I think they refused to shed blood because Gorbachev’s reforms introduced a willingness for people to think for themselves,” Braithwaite muses. “A lot of the soldiers thought: ‘Why would we want to reverse this freedom? Why would we want to spill Russian blood in Moscow?’ To my mind, that was due to Gorbachev’s earlier efforts – to his lasting credit. It could have been very nasty, but it wasn’t.”

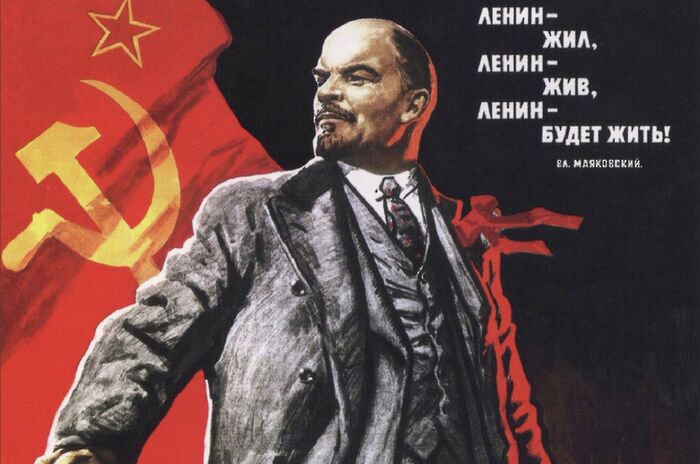

Ironically, the conspirators’ ‘patriotic act’ hastened the end of USSR: Gorbachev dissolved the Soviet Union on Christmas Day 1991. As the hammer and sickle flag was lowered for the last time over the Kremlin, a fleeting opportunity for liberal democracy and genuine free markets emerged. However, the events of 1991 did not mark the dawn of a democratic Russian idyll. I ask Braithwaite why the democratic experiment failed.

“Three reasons, really,” he replies. “First, it was bungled: the mishandling of state apparatus was appalling. Secondly, it was corrupt. The subsequent emergence of the oligarchs and the corruption of the 1996 election demonstrates that. The third problem was Yeltsin.”

Braithwaite sighs. “Gorbachev believed in institutions – organisations, sometimes democratic, which would hold power together in Russia. Yeltsin believed in a kind of populism, rather than democracy.”

“The Yeltsin years were full of hope for us and full of despair for the Russians”

“Ironically, it was a democratic system of voting, introduced by Gorbachev, which brought Yeltsin to power. But Yeltsin was only interested in maintaining that power, rather than the institutions which gave it to him. He was unable to resist American blandishments and, above all, he presided over an enormous economic chaos and decline.”

The scale of economic damage was huge: Russia’s GDP halved over the 1990s. “The Yeltsin years were full of hope for us and full of despair for the Russians,” Braithwaite explains. “It was a horrible decay for the Russians: there were fears of mass starvation; people weren’t paid for months on end; high inflation ruined peoples’ savings. Those problems were partly blamed on Gorbachev, and partly on Yeltsin.”

The same problems led to the rise of Putin. When Gorbachev dissolved the Soviet Union on Christmas Day 1991, Vladimir Putin was still a KGB officer. He had stood by and watched while East Germans celebrated the fall of the Berlin Wall and watched again as the USSR crumbled: for him, the collapse of Russia power wasn’t just a defeat, but a personal humiliation.

“The Bolsheviks may have disappeared for good when Yeltsin climbed atop a tank in August 1991, but the legacy of authoritarian rule remains”

“Putin came to power just as the oil price went up,” Braithwaite observes. “He rode an economic up-tick, although he – like Yeltsin and Gorbachev – has yet to find a stable platform for the Russian economy. But Putin has a plan for rebuilding Russian prestige. Unlike Yeltsin, he doesn’t get drunk; he doesn’t mess around. He is a fearsome political operator.”

As the interview draws to a close, I note the significance of discussing the collapse of the Soviet Union in the centenary of the Russian Revolution. The Soviet residue certainly lingers over Putin. The Bolsheviks may have disappeared for good when Yeltsin climbed atop a tank in August 1991, but the legacy of authoritarian rule remains.

Orlando Figes: The Memory of Revolutionary Russia

In Russia today, there is no concept of a loyal opposition, no separation of powers, and no mass participation in political life. Soviet rule, beginning and ending with two different coups, has left Russia with a “winner-takes-all” view of politics.

It seems that Putin has mastered the art of winning

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025

Music / The pipes are calling: the life of a Cambridge Organ Scholar25 April 2025 Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025

Arts / Plays and playing truant: Stephen Fry’s Cambridge25 April 2025 Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025

Comment / Cambridge builds up the housing crisis25 April 2025 Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025

Interviews / Dr Ally Louks on going viral for all the wrong reasons25 April 2025 News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025

News / Candidates clash over Chancellorship25 April 2025